© Commonwealth of Australia 2007

This work is copyright. Apart for any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Director of National Parks. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to:

Assistant Secretary

Parks Australia North

GPO Box 1260

Darwin NT 0801

This Management Plan aims to provide the general public and park users/visitors with information about how it is proposed the park will be managed for the next seven years. An electronic copy of this Plan is at http://www.deh.gov.au/parks/publications/index.html and additional hard copies are available from the Department of the Environment and Heritage Community Information Unit (phone 1800 803 772).

Note: Throughout this document, the term Bininj is used to refer to traditional owners of Aboriginal land and traditional owners of other land in the Park, and other Aboriginals entitled to enter upon or use or occupy the Park in accordance with Aboriginal tradition governing the rights of that Aboriginal or group of Aboriginals with respect to the Park.

Bininj is a Kunwinjku and Gundjeihmi word, pronounced ‘bin-ing’. This word is similar to the English word ‘man’ and can mean man, male, person or Aboriginal people, depending on the context. The word for woman in these languages is Daluk. Other languages in Kakadu National Park have other words with these meanings, for example the Jawoyn word for man is Mungguy and for woman is Alumka, and the Limilngan word is for man is Murlugan and Ugin-j for woman. The Board of Management has agreed to use the term Bininj for the purposes of this Management Plan.

Cover design: The cover design represents the natural, cultural, visitor experience and joint management values, and future, of Kakadu National Park as well as the importance placed on younger generations having opportunities to appreciate and understand these values. The art work was supplied by students from the Jabiru, Pine Creek, and Kunbarllanja (Oenpelli) Area Schools. The Kakadu National Park Board expresses it’s thanks to the students and schools for providing this artwork.

Kakadu is Aboriginal land. We Aboriginal people have obligations to care for our country, to look after djang, to communicate with our ancestors when on country and to teach all of this to future generations.

Aboriginal people and Park managers are walking together, side by side, to look after Kakadu country, look after culture.

The vision for Kakadu National Park is that it is one of the great World Heritage areas recognised internationally as a place where:

The guiding principles for the management of Kakadu National Park are that:

Foreword

Kakadu National Park is, and always has been, Bininj land. The evidence for this is in the World Heritage rock art and archaeological sites throughout the Park and Bininj people’s traditional connection to land and our culture. The long and continuing history of Bininj custodianship of Kakadu is one of the most important things about the Park, recognised in its World Heritage listing.

Traditional owners and managers of Kakadu have strong responsibilities and obligations to care for country and to guide and look after visitors.

Since the late 1970s, traditional owners have leased back their country to the Director of National Parks as part of Kakadu National Park. Through joint management, they have worked hard with Park staff to balance the protection of their culture and the places that are important to them with the needs of Park visitors and other stakeholders.

The Kakadu National Park Board of Management and the Director of National Parks wrote this management plan. When writing this Plan, the Board and the Director worked together:

The Plan will guide how Kakadu National Park is to be managed over the next seven years.

Kakadu National Park Board of Management

Acknowledgments

The Director of National Parks and the Kakadu National Park Board of Management are grateful to the many individuals and organisations who contributed to this Management Plan. In particular they acknowledge Bininj, Parks Australia staff, the Northern Land Council, and the Northern Territory and Australian Government agencies that provided information and assistance or submitted comments that contributed to the development of this Management Plan.

Jonathon Nadji (outgoing Chairperson 2005)

Jacob Nayinggul (incoming Chairperson 2005)

Jessie Alderson

Roy Anderson

Michael Bangalang

Jane Christophersen

Peter Cochrane

Bessie Coleman

Victor Cooper

Russell Cubillo (outgoing Deputy Chairperson 2005)

Anne-Marie Delahunt

Jeffrey Lee

Yvonne Margurula

Mick Markham

Sandra McGregor

Rick Murray

Marilynne Paspaley

Peter Wellings

Peter Whitehead

Denise Williams

Mr Willika (deceased)

Contents

Vision and Guiding principles

Foreword

Acknowledgments

Members of the Kakadu National Park Board of Management 2000–2005

Kakadu – a brief description 1

Bininj cultural rules for the management of Kakadu National Park 1

Establishment of Kakadu National Park 4

Joint management 5

Local, regional, national and international significance 7

1. Background 17

1.1. Previous Management Plans 17

1.2. Structure of this Management Plan 17

1.3. Planning process 17

2. Introductory provisions 18

2.5 Purpose, content and matters to be taken into account in a management plan 24

3. IUCN category 30

3.1 Assigning the Park to an IUCN category 30

4.2 Opportunities for Bininj from country 36

5. Looking after country and culture 42

5.1 Bininj cultural heritage management 42

5.2 Aboriginal sites of significance 44

5.3 Rock art and archaeological sites 46

5.4 Historic sites 48

5.5 Coastal management 49

5.6 Landscapes, soils and water 52

5.7 Fire 59

5.8 Native plants and animals 63

5.11 Weeds and introduced plants 71

5.12 Feral and domestic animals 72

6. Visitor management and Park use 77

6.1 Recreational opportunities and tourism directions 77

6.2 Access and site management 79

6.3 Access by road 80

6.4 Access by air 82

6.5 Visitor safety 83

6.6 Camping 85

6.7 Day walks and overnight bushwalking 86

6.8 Swimming 90

6.9 Other recreational activities and public gatherings 91

6.10 Boating and fishing 93

6.11 Visitor information, education and interpretation 97

6.12 Promotion and marketing 98

6.13 Filming, photography and audio recording 100

6.14 Commercial tour activities 101

6.15 Commercial accommodation 104

7. Stakeholders and partnerships 106

7.1 Jabiru 106

7.2 Neighbours, stakeholders and partnerships 116

8.2 Compliance and enforcement 120

8.3 Assessment of proposals 121

8.4 Incident management 125

8.5 Leases, licences and associated occupancy issues 127

8.6 Research and monitoring 132

8.7 Resource use in Park operations 132

8.8 New activities not otherwise specified in this Plan 133

8.9 Management Plan implementation and evaluation 134

A Provisions of leases between Aboriginal Land Trusts 137

and Director of National Parks

B World Heritage attributes of Kakadu National Park 159

D Threatened species occurring in Kakadu National Park 164

E EPBC listed migratory species occurring in Kakadu National Park 166

F Ramsar information sheet 169

G Management principles schedules 174

Figures

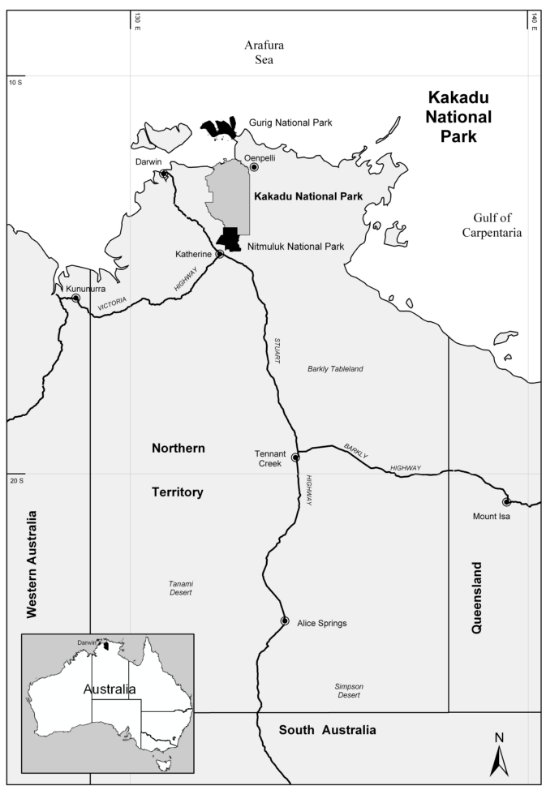

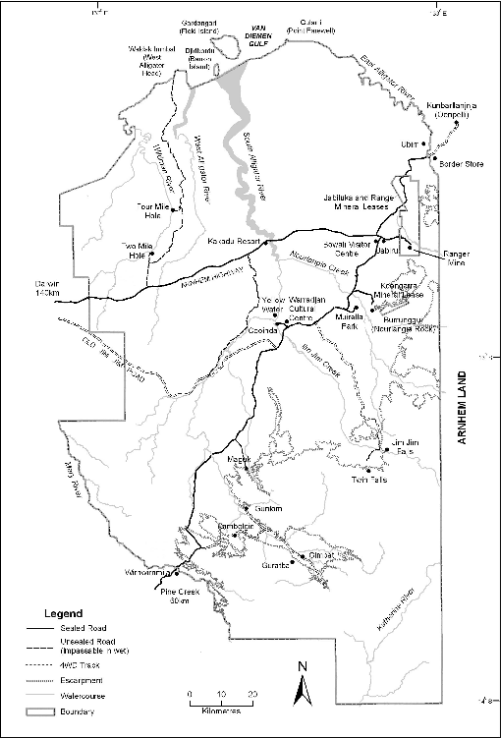

1 Location of Kakadu National Park 2

2 Kakadu National Park 6

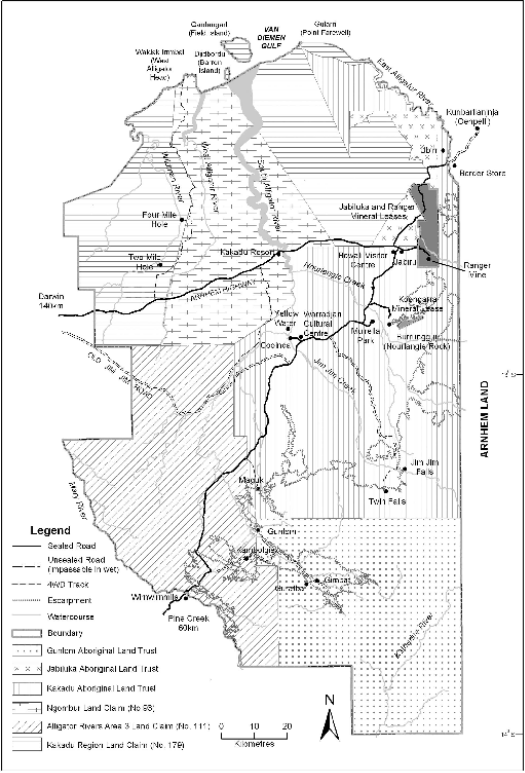

3 Aboriginal land and land claims in Kakadu National Park 8

4 Landforms of Kakadu 55

5 Mine rehabilitation sites 57

6 Camping and day use areas 88

7 Areas closed to recreational fishing 96

Bibliography 180

![]()

![]()

Kakadu National Park covers an area of 19 804 square kilometres within the Alligator Rivers Region of the Northern Territory of Australia. It extends from the coast in the north to the southern hills and basins 150 kilometres to the south, and 120 kilometres from the Arnhem Land sandstone plateau in the east through wooded savannas to the western boundary (see Figure 1).

Kakadu National Park is an Aboriginal living cultural landscape. A strong relationship exists between Bininj and their country, ongoing traditions, cultural practices, beliefs and knowledge. The living Aboriginal culture in Kakadu is diverse as there are many different clan groups with associations to country in Kakadu. Each clan group is responsible for looking after and speaking for particular areas of country in Kakadu, and this responsibility has been passed down from previous to present generations. The management and use of the land by past and present generations of Bininj has helped to shape the landscapes that we see in Kakadu today.

The Park is ecologically and biologically diverse. Major landforms and habitats within the Park include the sandstone plateau and escarpment, extensive areas of savanna woodlands and open forest, rivers, billabongs, floodplains, mangroves, mudflats, coastal areas and monsoon forests.

The value of the natural and cultural heritage of the Park to the world has been recognised by its inscription on the World Heritage List under the World Heritage Convention. The Park includes a large area that is listed as a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar Convention, and many species that occur in the Park are protected under international agreements such as the Bonn Convention for conserving migratory species and Australia’s migratory bird protection agreements with China (CAMBA) and Japan (JAMBA).

The Alligator Rivers Region, which includes Kakadu, is on the Register of the National Estate under the Australian Heritage Council Act 2003 because of its national significance to the Australian people. At the time of preparing this Plan Kakadu as a whole and some sites in the Park are also under consideration for inclusion in the National Heritage List or Commonwealth Heritage List under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act).

Every culture has a creation story. Aboriginal people believe that they have been here from the time of the first ancestors or Nayuhyunggi (in the Gundjeihmi language) when landscapes formed, human beings transformed themselves into animals and sacred places set themselves into the landscape.

Creation ancestors came in many forms. The Rainbow Snake (Almudj/Alyod in Gundjeihmi and Bolung in Jawoyn) is a spiritual being of great significance in Aboriginal culture in Kakadu. Other ancestral beings include Bula (in the Jawoyn language), Namarrgon (Lightning Man), Warramurrungundji (Earth Mother) and

Figure 1 – Location of Kakadu National Park

others. The landscape and its features were left by the Creation Ancestors. They instituted and created ceremonies, rules to live by, laws, plants, animals and people, then they turned into djang (dreaming places and their spiritual essence). They taught Aboriginal people how to live with the land. From then on Aboriginal people became keepers of their country.

‘We Aboriginal people have obligations to care for our country, to look after djang, to communicate with our ancestors when on country and to teach all of this to the next generations.’ (combined statement from the Aboriginal members of the Kakadu Board of Management)

Every aspect of life and responsibilities for looking after country is governed by kinship ties. Aboriginal languages have special linguistic features that eloquently express these ties and responsibilities.

Aboriginal society is organised into many kinds of social divisions. All people, plants, animals, places, weather, landscapes and ceremonies are divided into halves or moieties such as Duwa and Yirridjdja, Mardku and Ngarradjku.

Each moiety is subdivided into four pairs of subsections or ‘skin groups’. A child’s skin group is determined by that of their mother but they inherit their moiety from their father. Through the use of skin groups Aboriginal people organise marriage relationships and use skin group names as important ways of addressing and referring to other Aboriginal people.

Members of a particular clan have a number of clan totems or emblems that are associated with the clan and its moiety. Such totems have their religious focus in special places or sacred sites in their clan estates. If the totem is a plant or animal that is relied upon as a food source, then members of the owning clan have responsibilities to ensure the plentiful supply of this food.

Kakadu includes the traditional lands of a number of Aboriginal clan groups.

‘Land and people go together. Every place has a clan name, and every place has a clan.’

Jacob Nayinggul, Manilagarr clan

In English the term ‘traditional owner’ is commonly used to refer to someone who is a member of the clan associated with a particular clan estate (and has a particular meaning under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976). Both men and women may be acknowledged as senior traditional owners. Traditional owners make important decisions about the management of a clan estate through patrilineal descent. Aboriginal people who are connected to a clan estate through their mother are also involved in decision-making. These people, who refer to a clan estate as their mother’s country, have important management responsibilities, namely protecting sacred sites and assisting with the protection of religious objects associated with their mother’s country.

‘These laws need to be explained to non-Aboriginal people in the same way it is taught to children so we can all hold on to it and teach it to children who will grow up learning about their land with this law.’ (Jacob Nayinggul, Manilagarr clan)

Making decisions about country

Bininj who have cultural responsibilities for management of a clan estate are key people in the planning and management of the Park. Everyone who lives, works in or visits Kakadu must respect Bininj rules and it is important that these rules are passed on to young Bininj.

‘I had to learn it when I was growing up and I have to teach it to my family – my sisters and brothers have to learn it. Parks needs to learn it too.’ (Senior Jawoyn Bolmo clan member)

‘Bininj/Mungguy try hard to learn Balanda law to make informed decisions. Balanda need to make an effort to learn Bininj/Mungguy law.’ (Russell Cubillo, Jawoyn Bolmo affiliate)

‘Bininj laws must be followed, with Balanda law backing up Bininj law.’ (Jonathon Nadji, Bunitj clan)

‘When I want to do something on country I have to ask the right person. To go and burn country or do weed control I have to ask the right person, traditional way, because there’s many important sites there or whatever. This is our way.’ (Bessie Coleman, Wurrkbarbar clan)

Background

Kakadu was established at a time when the Australian community was becoming more interested in the declaration of national parks for conservation and in recognising the land interests of Aboriginal people. A national park in the Alligator Rivers Region was proposed as early as 1965. Over the next decade several proposals for a major national park in the region were put forward by interested groups and organisations. One of these proposals first suggested the name ‘Kakadu’, after the Gagudju people, for the national park. ‘Kakadu’ was the original spelling of the word as given by the biologist and anthropologist W Baldwin Spencer in 1912.

In 1973, the Australian Government set up a Commission of Inquiry into Aboriginal land rights in the Northern Territory. This commission specially considered how to recognise Aboriginal people’s land interests while providing for conservation management of the land. The commissioner in charge of this inquiry, Mr Justice Woodward, concluded that: ‘It may be that a scheme of Aboriginal title, combined with national park status and joint management would prove acceptable to all interests.’ (Woodward 1973).

In the early 1970s, significant uranium deposits were discovered in the Alligator Rivers Region at Ranger, Jabiluka and Koongarra. A formal proposal to develop the Ranger deposit was submitted to the Australian Government in 1975 and the Government established the Ranger Uranium Environmental Inquiry to investigate the proposal, focusing on environmental issues and the social impact on Aboriginal people.

During the time the inquiry was held, the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Land Rights Act) was passed by the Commonwealth Parliament. The Land Rights Act allowed the Commission, set up to conduct the Ranger Inquiry, to determine the merits of a claim to traditional Aboriginal ownership of land in the Alligator Rivers Region.

The Ranger Inquiry tried to work out a compromise between the problems of conflicting and competing land uses, including Aboriginal people living on the land, establishing a national park, uranium mining, tourism and pastoral activities in the Alligator Rivers Region. In August 1977, the Australian Government responded to the recommendations of the Ranger Inquiry. It accepted almost all the recommendations including those about granting Aboriginal title to areas in the Alligator Rivers Region and establishing Kakadu in stages. An arrangement was made for the traditional owners to lease land granted to them to the Australian Government for management as a national park. Mining would not be permitted in the Park but was provided for on areas excluded from the Park.

Establishment of the Park, and the Park as Aboriginal land

Kakadu National Park was declared under the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1975 (NPWC Act) in three stages between 1979 and 1991. The NPWC Act was replaced by the EPBC Act in 2000. The declaration of the Park continues under the EPBC Act. Each stage of the Park includes Aboriginal land under the Land Rights Act that is leased to the Director of National Parks (the Director), or land that is subject to a claim to traditional ownership under the Land Rights Act (see Figure 3).

Most of the land that was to become part of Stage One of Kakadu was granted to the Kakadu Aboriginal Land Trust under the Land Rights Act in August 1978 and, in November 1978, the Land Trust and the Director signed a lease agreement for the land to be managed as a national park. Stage One of the Park—covering the leased land, and land required for the township of Jabiru and some adjoining areas—was declared on 5 April 1979.

Stage Two was declared on 28 February 1984. In March 1978, a claim was lodged under the Land Rights Act for the land included in Stage Two of Kakadu. The land claim was partly successful and, in 1986, three areas in the eastern part of Stage Two were granted to the Jabiluka Aboriginal Land Trust. A lease between the Land Trust and the Director of National Parks was signed in March 1991.

In June 1987, a land claim was lodged for the land in the former Goodparla and Gimbat pastoral leases that were to be included in Stage Three of Kakadu. The other areas to be included in Stage Three—the area known as the Gimbat Resumption and the Waterfall Creek Reserve (formerly known as UDP Falls, UDP standing for Uranium Development Project)—were later added to this land claim. Stage Three of Kakadu was declared progressively on 12 June 1987, 22 November 1989 and 24 June 1991. The progressive declaration was due to the debate over whether mining should be allowed at Guratba (Coronation Hill) which is located in the middle of the culturally significant area referred to as the Sickness Country. The traditional owners’ wishes were ultimately respected and the Australian Government decided that there would be no mining at Guratba. In 1996, the land in Stage Three, apart from the former Goodparla pastoral lease, was granted to the Gunlom Aboriginal Land Trust and leased to the Director of National Parks to continue being managed as part of Kakadu.

Joint management

Joint management is about Bininj and Balanda working together, solving problems together, sharing decision-making responsibilities and exchanging knowledge, skills and information. Important objectives of joint management are to make sure that traditional skills and knowledge associated with looking after culture and country, and Bininj cultural rules regarding how decisions should be made, continue to be respected and maintained. It is also important that contemporary park management skills are available to enable the joint management partners to look after Kakadu in line with current best management practices.

Joint management in Kakadu combines a legal framework set in place by the NPWC Act (continued under the EPBC Act), the Land Rights Act, the lease agreements between Aboriginal Land Trusts and the Director and the continuing day-to-day relationship between Bininj, the Park Board of Management and Park staff.

Figure 2 – Kakadu National Park

The Land Rights Act provides for the granting of land to Aboriginal Land Trusts for the benefit of the traditional Aboriginal owners and requires land granted in the Alligator Rivers Region to be leased to the Director of National Parks. The EPBC Act provides for the Park to be managed by the Director in conjunction with the traditional owners through a Board of Management that has a majority of members who are nominated by Bininj. The role of the Board is to prepare management plans with the Director, make decisions to implement those plans (including allocation of resources and setting priorities), monitor management of the Park and provide advice to the responsible Minister (currently the Minister for the Environment and Heritage). The EPBC Act requires the composition of the Board to be agreed between the Minister (who appoints Board members) and the Northern Land Council. At the time of preparing this management plan, the Kakadu Board has 15 members, 10 of whom are nominated by the traditional owners of land in the Park.

The Bininj representation on the Board covers the geographic spread of Aboriginal people within the Kakadu region as well as the major language groupings. At the time of writing, the Balanda members of the Board are the Director of National Parks; the Assistant Secretary of Parks Australia North; a person prominent in nature conservation; a person employed in the tourism industry in the Northern Territory; and a Northern Territory nominee. The Board has determined that the Chairperson be appointed from the Aboriginal members of the Board.

As well as being important to Bininj, Kakadu is a special and important place to many other people.

How Kakadu is significant locally

To Bininj, Kakadu is of particular importance as it is their home and they have important cultural obligations to look after country. Many Bininj consider that they cannot or should not move to other places to live or work. The Park is their traditional homeland and it is important to them that they are able to look after their country and culture and make sure that visitors to their country are safe. Many other people also enjoy the benefits that come from living in the Park. For many residents in Jabiru and the Kakadu region, Kakadu is not only a place to live and work, it is also a place for recreation and a place where they can appreciate and learn about the Park’s natural and cultural heritage.

How Kakadu is significant regionally

Conservation: The Park is both representative and unique. It is representative of the ecosystems of a vast area of northern Australia. It is unique because it incorporates one drainage basin (the South Alligator River) and all of the major habitat types of the Top End. It is where the Arnhem Land plateau meets the Alligator Rivers floodplains and the southern hills and basins (see Figure 4, Landforms of Kakadu).

A number of plant and animal species that occur in Kakadu do not occur in any other national park. Kakadu is important as a wildlife conservation area for the region because it is a large area managed as a national park, whereas other areas of Top End habitats are managed primarily for other purposes such as agriculture, pastoralism, mining, rural development or defence force use, or are not being actively managed for habitat conservation.

It is essential for regional conservation that traditional owners of Kakadu, Nitmiluk, Gurig, Arnhem Land and other areas in the region, Park staff and external specialists share their knowledge of country and, where needed, carry out cooperative land management and conservation programs. This requires cooperative arrangements between Parks Australia,

Figure 3 – Aboriginal land and land claims in Kakadu National Park

Northern Territory Government agencies, Aboriginal organisations and other organisations. Regional conservation initiatives are a key component of this Plan.

Regional economy: Tourism is very important to the regional economy, particularly in terms of employment. For the financial year 2004–05, the Northern Territory Tourist Commission reported that the direct value of tourism to the Territory was $1.5 billion, generated from over 1.4 million visitors. Of all visitors to the Northern Territory, 82 per cent visited for pleasure and most report they visit to take advantage of attractions such as those provided by Kakadu. In 2004/05, Kakadu National Park attracted 165,300 visitors . It is estimated that tourism in Kakadu directly contributed $58.1 million to the Northern Territory economy in 2004-05 (Tremblay 2005). In addition to its significant contribution via the tourism market, the Park purchases significant quantities of goods and services from regional suppliers. Further analyses of the economic significance of the Park are being developed, including the economic value of the environmental services that the Park provides.

It is important to the Northern Territory Government that tourism development in the Park complements its tourism marketing strategies and plans for regional tourism development.

Recreation: Many people from Darwin, Katherine and Pine Creek use the Park for recreation. They undertake many recreational activities in the Park with fishing, camping, bushwalking and visiting with relatives and friends being some of the most popular activities. Kakadu offers recreational opportunities that complement those offered in the other parks, reserves and attractions in the region, such as the proposed Mary River National Park, Nitmiluk, Litchfield and Gurig national parks, Fogg Dam, Window on the Wetlands and the Territory Wildlife Park.

How Kakadu is significant nationally

Conservation: Nearly 1600 plant species have been recorded in Kakadu, including about 17 species considered rare or threatened. Kakadu contains 271 bird species, which is over one third of Australia’s bird fauna, and 77 mammal species, about one quarter of Australia’s land mammals; 132 species of reptiles and 27 species of frogs are located within Kakadu and over 246 species of fish have been recorded in tidal and freshwater areas within the Park. The region is the most species-rich in freshwater fish in Australia. Unlike many other areas of Australia, Kakadu still has nearly all the plant and animal species that are thought to have been present in the area 200 years ago. Additional species new to western science have also been discovered in the Park since its inscription, including the freshwater tongue sole, the giant cave gecko and an undescribed species of Acacia.

In 1980, the significance of the Alligator Rivers Region to the nation was recognised by its entry on the Register of the National Estate under the Australian Heritage Commission Act 1975 because of its natural and cultural heritage. In 1986, 575 ha at Jarrangbarnmi (Koolpin Gorge) was placed on the register because the endemic species Eucalyptus koolpinensis is found there. The southern third of the Park was placed on the register in 1989. The EPBC Act has replaced the Australian Heritage Commission Act 1975 with new heritage protection provisions but the Register of the National Estate continues under the Australian Heritage Council Act 2003. The EPBC Act requires the Minister for the Environment and Heritage to have regard to information in the Register of the National Estate when making decisions under the Act.

At the time of preparing this Plan, Kakadu and some sites in the Park that are on the Register of the National Estate are ‘indicative places’ for the purposes of potential inclusion in either the National Heritage List or Commonwealth Heritage List under the EPBC Act.

The national park status and effective conservation management of Kakadu contribute significantly towards meeting the objectives of a number of Australian national conservation strategies. These include the following:

National Forest Policy Statement. Substantial areas of a number of types of tropical forest, as well as large tracts of savanna woodland, are conserved in Kakadu, contributing to the objective of having a comprehensive, adequate and representative network of dedicated and secure nature conservation reserves for forest ecosystems.

National Reserve System. The National Reserve System represents the collective efforts of the states, territories, the Australian Government, non-government organisations and Indigenous landholders to achieve an Australian system of terrestrial protected areas as a major contribution to the conservation of our native biodiversity.

Kakadu makes a significant contribution to the National Reserve System, which aims to contain samples of all regional ecosystems across Australia, their constituent biota and associated conservation values, in accordance with the Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia. Kakadu spans two biogeographic regions—Arnhem Plateau and Pine Creek. The Arnhem Plateau biogeographic region encompasses the Territory’s most important area for biodiversity with very high levels of endemism and extraordinary richness of many groups of flora and fauna. About 20 per cent is within reserves, Kakadu accounting for most of this. The Pine Creek biogeographic region is the most extensively reserved of the Territory bioregions, with 43 per cent in reserves, most of which is in Kakadu. These are amongst the highest levels of protection in the country (Department of Natural Resources, Environment and the Arts 2005).

Wetlands Policy of the Commonwealth Government of Australia. Kakadu conserves almost all the catchment of the South Alligator River as well as large areas of wetlands, contributing to all objectives of the Wetlands Policy, particularly the objective of managing wetlands in an ecologically sustainable way and within a framework of integrated catchment management. A guiding principle of the Wetlands Policy is recognition of the importance of the knowledge and practices of Indigenous people in relation to wetlands and promotion of a cooperative approach to wetland management and conservation with Indigenous Australians. The joint management arrangements in Kakadu are consistent with this guiding principle.

National economy: Tourism is the fastest growing export industry in Australia and is actively promoted by governments at all levels. Along with other places of natural beauty in Australia such as Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park and the Great Barrier Reef, Kakadu has become a major tourism attraction for overseas visitors.

Joint management: The management arrangements in the Park between Bininj and Parks Australia continue to be cited as an example of an innovative and effective cooperative management arrangement. The joint management of Kakadu has led to international praise for Australia, the Australian Government and the joint management partners.

Protected area and land management authorities and groups of Indigenous people interested in joint management from within Australia and overseas regularly visit the Park.

How Kakadu is significant internationally

Kakadu is inscribed on the World Heritage List under the World Heritage Convention for its outstanding natural and cultural values. Stage One of the Park was inscribed on the list in 1981 and Stage Two in 1987. The whole of the Park was listed in December 1992. Kakadu is one of the few sites that are listed under the World Heritage Convention for both cultural and natural values. At the time of preparing this Plan, Kakadu is one of only 23 World Heritage sites listed for both its natural and cultural heritage. Appendix B to this Plan summarises the World Heritage criteria and attributes of Kakadu.

Large areas of Kakadu are listed as wetlands of international importance under the Ramsar Convention. Stage One was included on the list in 1980. Wetlands in Stage Two were included in September 1987. In 1996, wetlands in Stage Three that are part of the South Alligator River catchment were added to the list. Some 683 000 ha of Kakadu are included in the Ramsar list. Appendix F to this Plan contains the Ramsar information sheet for the Park.

In March 1996, the parties to the Ramsar Convention agreed to establish an East Asian–Australasian Flyway to protect areas used by migratory shorebirds. The Flyway provides for an East Asian–Australasian shorebird reserve network of sites that are critically important to migratory shorebirds. The wetlands of Kakadu National Park are part of this reserve network.

Numerous migratory species that occur in Kakadu are protected under international agreements such as the Bonn Convention for conserving migratory species, and Australia’s migratory bird protection agreements with China (CAMBA) and Japan (JAMBA). Thirty-nine of the species listed under the Bonn Convention are found in Kakadu, as are 52 of the 81 birds listed under CAMBA and 49 of the 110 birds listed under JAMBA. Appendix E to this Plan lists the migratory species that occur in the Park.

Kakadu is part of a Tri-National Wetlands Conservation Project which operates under an agreement between the Director of National Parks and the management authorities of Wasur National Park in Irian Jaya and Tonda Wildlife Management Area in Papua New Guinea. The project aims to develop a cooperative arrangement between the three areas to share experiences in wetland conservation, promote best management options and develop local management capacity. Wetlands in the three protected areas each form a significant stop-over point for birds on the East Asian–Australasian Flyway.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

1. Background

Part 1 of the Plan sets out the context in which this 5th Plan was prepared. It describes previous Plans and the network of legislative requirements, lease agreements and international agreements which underpin the content of the Plan.

1.1 Previous Management Plans

This is the 5th Management Plan for Kakadu National Park. The 4th Plan came into operation on 11 March 1999 and ceased to have effect on 8 March 2004.

The structure of this Plan reflects the Parks Australia Strategic Planning and Performance Assessment Framework, a set of priorities based on Australian Government policy and legislative requirements for the protected area estate that is the responsibility of the Director of National Parks.

The outcomes in the Plan are developed against the following Key Result Areas (KRAs) reflected in the Strategic Planning and Performance Assessment Framework:

KRA 1: Natural heritage management (see Section 5 of the Plan)

KRA 2: Cultural heritage management (see Section 5)

KRA 3: Joint management (see Section 4)

KRA 4: Visitor management and park use (see Section 6)

KRA 5: Stakeholders and partnerships (see Section 7)

KRA 6: Business management (see Section 8).

Not all KRAs apply to all reserves; KRA 7, Biodiversity knowledge management, does not apply to Kakadu. Appendix C details outcomes for the KRAs, which are also used to structure the State of the Parks report in the Director of National Parks’ Annual Report to the Australian Parliament.

1.3 Planning process

Section 368 of the EPBC Act requires that the Director of National Parks and the Board of Management (if any) for a Commonwealth reserve prepare management plans for the reserve. In addition to seeking comments from members of the public, the relevant land council and the relevant state or territory government, the Director and the Board are required to take into account the interests of the traditional owners of land in the reserve and of any other Indigenous persons interested in the reserve.

The Kakadu National Park Board of Management resolved that consultations be undertaken with Bininj on a clan-by-clan basis to seek comments on issues related to the management of the Park. During the drafting stage of this Plan, Park staff conducted extensive consultations with over 100 Bininj during 33 participatory planning meetings. These meetings covered a range of Park management issues including decision-making procedures; natural and cultural resource management; visitor management and Park use and Bininj employment. A number of Board meetings were also conducted to enable the Board to consider the draft Management Plan and submissions received from members of the public.

Other stakeholder groups and individuals that were consulted during the preparation of this Management Plan include:

2. Introductory provisions

2.1 Short title

This Management Plan may be cited as the Kakadu Management Plan or the Kakadu National Park Management Plan.

2.2 Commencement and termination

This Management Plan will come into operation following approval by the Minister under Section 370 of the EPBC Act, on a date specified by the Minister or the date it is registered under the Legislative Instruments Act 2003, and will cease to have effect seven years after commencement, unless revoked sooner or replaced with a new Plan.

2.3 Interpretation (including acronyms)

In this Management Plan:

Aboriginal means a person who is a member of the Aboriginal race of Australia

Aboriginal land means

(a) land held by an Aboriginal Land Trust for an estate in fee simple under the Land Rights Act; or

(b) land that is the subject of a deed of grant held in escrow by an Aboriginal Land Council under the Land Rights Act

Aboriginal tradition means the body of traditions, observances, customs and beliefs of Aboriginals generally or of a particular group of Aboriginals and includes those traditions, observances, customs and beliefs as applied in relation to particular persons, sites, areas of Kakadu National Park, things and relationships

Australian Government means the Government of the Commonwealth of Australia

Balanda means non-Aboriginal people

BFC means the Bushfires Council established by the Bushfires Act (NT)

Bininj means traditional owners of Aboriginal land and traditional owners of other land in the Park, and other Aboriginals entitled to enter upon or use or occupy the Park in accordance with Aboriginal tradition governing the rights of that Aboriginal or group of Aboriginals with respect to the Park. (This includes Relevant Aboriginals as defined in the lease agreements for the Park)

Note: Bininj is a Kunwinjku and Gundjeihmi word, pronounced ‘bin-ing’. This word is similar to the English word ‘man’ and can mean man, male, person or Aboriginal people, depending on the context. Other languages in Kakadu National Park have other words with these meanings, for example the Jawoyn word is Mungguy and the Limilngan word is Murlugan. In this plan, the word Bininj is used to refer to Aboriginal people who have rights and interests in relation to Kakadu National Park

Board of Management or Board means the Board of Management for Kakadu National Park established under the NPWC Act and continued under the EPBC Act by the Environmental Reform (Consequential Provisions) Act 1999

CAMBA means Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of the People's Republic of China for the Protection of Migratory Birds and their Environment

CITES means the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora

Commonwealth reserve means a reserve established under Division 4 of Part 15 of the EPBC Act

Director means the Director of National Parks under section 514A of the EPBC Act, and includes Parks Australia and any person to whom the Director has delegated powers and functions under the EPBC Act in relation to Kakadu National Park

EPBC Act means the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, including Regulations under the Act, and includes reference to any Act amending, repealing or replacing the EPBC Act

EPBC Regulations means the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Regulations 2000 and includes reference to any Regulations amending, repealing or replacing the EPBC Regulations

ERA means Energy Resources Australia

eriss means the Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist

EPARR Act means the Environment Protection (Alligator Rivers Region) Act 1978

Gazette means the Commonwealth of Australia Gazette

GIS means geographic information system

ICOMOS means the International Council on Monuments and Sites

IUCN means the World Conservation Union

JAMBA means Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of Japan for the Protection of Migratory Birds and Birds in Danger of Extinction and their Environment

JTC means the Jabiru Town Council

JTDA means the Jabiru Town Development Authority, or its successor.

Kakadu National Park, Kakadu or the Park means the area declared as a Park by that name under the NPWC Act and continued as a Commonwealth reserve under the EPBC Act by the Environmental Reform (Consequential Provisions) Act 1999

KRAC means the Kakadu Research Advisory Committee

KTCC means the Kakadu Tourism Consultative Committee

Land Rights Act means the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976

Lease agreements means lease agreements between Aboriginal Land Trusts and the Director in respect of Aboriginal land in the Park

Management Plan or Plan means this Management Plan for the Park, unless otherwise stated

Management principles means the Australian IUCN reserve management principles set out in Schedule 8 of the EPBC Regulations (see Appendix F)

Mining operations means mining operations as defined by the EPBC Act

Minister means the Minister administering the EPBC Act

NLC means the Northern Land Council

NPWC Act means the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1975 and the Regulations under that Act

NT means the Northern Territory of Australia

NTFRS means the Northern Territory Fire and Rescue Service

OHS means occupational health and safety

OSS means the Office of the Supervising Scientist

Parks Australia means that part of the Department of the Environment and Heritage that assists the Director in performing the Director’s functions under the EPBC Act

RUEI means the Ranger Uranium Environmental Inquiry

Traditional owners means the traditional Aboriginal owners as defined in the Land Rights Act

World Heritage Convention means the Convention for the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage.

2.4 Legislative context

2.4.1 Land Rights Act and Park leases

At the time of preparation of this Management Plan approximately 50 per cent of Kakadu National Park is Aboriginal land under the Land Rights Act. Most of the remaining area of land is under claim by Aboriginal people. Title to Aboriginal land in the Park is held by Aboriginal land trusts. The land trusts have leased their land to the Director in accordance with the Land Rights Act for the purpose of being managed as a Commonwealth reserve. Land in the Park that is not Aboriginal land is vested in the Director.

2.4.2 EPBC Act

Objects of the Act

The objects of the EPBC Act as set out in Part 1 are:

(a) to provide for the protection of the environment, especially those aspects of the environment that are matters of national environmental significance; and

(b) to promote ecologically sustainable development through the conservation and ecologically sustainable use of natural resources; and

(c) to promote the conservation of biodiversity; and

(ca) to provide for the protection and conservation of heritage; and

(d) to promote a co-operate approach to the protection and management of the environment involving governments, the community, land-holders and indigenous peoples; and

(e) to assist in the co-operative implementation of Australia’s international environmental responsibilities; and

(f) to recognise the role of indigenous people in the conservation and ecologically sustainable use of Australia’s biodiversity; and

(g) to promote the use of indigenous people’s knowledge of biodiversity with the involvement of, and in cooperation with, the owners of the knowledge.

Establishment of the Park

The Park was declared under the NPWC Act progressively between 1979 and 1991. Stage One of the Park was established in 1979, Stage Two in 1984, and Stage Three between 1987 and 1991. The NPWC Act was replaced by the EPBC Act in July 2000. The Park continues as a Commonwealth reserve under the EPBC Act pursuant to the Environmental Reform (Consequential Provisions) Act 1999, which deems the Park to have been declared for the following purposes:

the preservation of the area in its natural condition

the encouragement and regulation of the appropriate use, appreciation and enjoyment of the area by the public.

Director of National Parks

The Director is a corporation under the EPBC Act (s.514A) and a Commonwealth authority for the purposes of the Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act 1997. The corporation is controlled by the person appointed by the Governor-General to the office that is also called the Director of National Parks (s.514F of the EPBC Act).

The functions of the Director (s.514B) include the administration, management and control of the Park. The Director generally has power to do all things necessary or convenient for performing the Director’s functions (s.514C). The Director has a number of specified powers under the EPBC Act and EPBC Regulations, including to prohibit or control some activities, and to issue permits for activities that are otherwise prohibited. The Director performs functions and exercises powers in accordance with this Management Plan and relevant decisions of the Kakadu Board of Management.

Kakadu Board of Management

The Kakadu Board of Management was established under the NPWC Act in 1989 and continues under the EPBC Act. A majority of Board members must be Indigenous persons nominated by the traditional Aboriginal owners of land in the Park. The functions of the Board under s.376 of the EPBC Act are:

- to make decisions relating to the management of the Park that are consistent with the Management Plan in operation for the Park; and

- in conjunction with the Director, to:

- prepare management plans for the Park; and

- monitor the management of the Park; and

- advise the Minister on all aspects of the future development of the Park.

Management plans

The EPBC Act requires the Board, in conjunction with the Director, to prepare management plans for the Park. When prepared, a plan is given to the Minister for approval. A management plan is a ‘legislative instrument’ for the purposes of the Legislative Instruments Act 2003 and must be registered under that Act. Following registration the plan is tabled in each House of the Commonwealth Parliament and may be disallowed by either House on a motion moved within 15 sitting days of the House after tabling.

A management plan for a Commonwealth reserve has effect for seven years, subject to being revoked or amended earlier by another management plan for the reserve.

See Section 2.5 in relation to EPBC Act requirements for a management plan.

Control of actions in Commonwealth reserves

The EPBC Act (s.354) prohibits certain actions being taken in Commonwealth reserves except in accordance with a management plan. These actions are:

These prohibitions, and other provisions of the EPBC Act and Regulations dealing with activities in Commonwealth reserves, do not prevent Aboriginal people from continuing their traditional use of Kakadu for hunting or gathering (except for purposes of sale) or for ceremonial and religious purposes (s.359A).

The EPBC Act also does not affect the operation of s.211 of the Native Title Act 1993, which provides that holders of native title rights covering certain activities do not need authorisation required by other laws to engage in those activities (s.8 EPBC Act).

Mining operations are prohibited in Kakadu National Park by the EPBC Act (s.387).

The EPBC Regulations control, or allow the Director to control, a range of activities in Commonwealth reserves, such as camping, use of vehicles and vessels, littering, commercial activities, commercial fishing, recreational fishing and research. The Director of National Parks applies the Regulations subject to and in accordance with the EPBC Act and management plans. The Regulations do not apply to the Director of National Parks or to wardens or rangers appointed under the EPBC Act. Activities that are prohibited or restricted by the EPBC Regulations may be carried on if they are authorised by a permit issued by the Director and/or they are carried on in accordance with a management plan or if another exception prescribed by r.12.06(1) of the Regulations applies.

As noted earlier, the Park was declared under the NPWC Act, which was replaced by the EPBC Act on 16 July 2000. The EPBC Act also replaced a number of other Commonwealth Acts, namely the:

Australian Heritage Commission Act 1975;

Endangered Species Protection Act 1992

Environment Protection (Impact of Proposals) Act 1974

Whale Protection Act 1980

Wildlife Protection (Regulation of Exports and Imports) Act 1982

World Heritage Properties Conservation Act 1983.

These other parts of the EPBC Act may also be relevant to the management of the Park and the taking of actions in, and in relation to, the Park.

Environmental impact assessment

Actions that are likely to have a significant impact on matters of ‘national environmental significance’ are subject to the referral, assessment and approval provisions of Chapters 2 to 4 of the EPBC Act (irrespective of where the action is taken).

At the time of preparing this Plan, the matters of national environmental significance identified in the EPBC Act are:

The referral, assessment and approval provisions also apply to actions on Commonwealth land that are likely to have a significant impact on the environment and actions taken outside Commonwealth land that are likely to have a significant impact on the environment on Commonwealth land. The Park is Commonwealth land for the purposes of the EPBC Act.

Responsibility for compliance with the assessment and approvals provisions of the EPBC Act lies with persons taking relevant ‘controlled’ actions. A person proposing to take an action that the person thinks may be or is a controlled action should refer the proposal to the Minister for the Minister’s decision whether or not the action is a controlled action. The Director of National Parks may also refer proposed actions to the Minister.

Wildlife protection

The EPBC Act also contains provisions (Part 13) that prohibit and regulate actions in relation to listed threatened species and ecological communities, listed migratory species, cetaceans (whales and dolphins) and listed marine species. Appendix D to this Plan lists species in the Park that are threatened under the EPBC Act and Northern Territory legislation, and Appendix E lists migratory species that are listed under the EPBC Act and international conventions, treaties and agreements.

Heritage protection

As noted above the EPBC Act has replaced the Australian Heritage Commission Act 1975. The Alligator Rivers region, Kakadu and some places within the Park were included in the Register of the National Estate established under that Act. The register continues under the Australian Heritage Council Act 2003. Section 391A of the EPBC Act requires the Minister to have regard to information in the Register of the National Estate in making any decisions under the EPBC Act to which the information is relevant.

At the time of preparing this Plan, Kakadu and some sites in the Park that are in the Register of the National Estate are ‘indicative places’ for the purposes of potential inclusion in either the National Heritage List or Commonwealth Heritage List under the EPBC Act.

The EPBC Act heritage protection provisions (ss. 324A to 324ZC and ss. 341A to 341ZH) relevantly provide:

- prepare a written heritage strategy for managing those places to protect and conserve their Commonwealth Heritage values, addressing any matters required by the EPBC Regulations, and not be inconsistent with the Commonwealth Heritage management principles; and

- identify Commonwealth Heritage values for each place, and produce a register that sets out the Commonwealth Heritage values (if any) for each place (and do so within the time frame set out in its heritage strategy).

Penalties

Civil and criminal penalties may be imposed for breaches of the EPBC Act.

2.5 Purpose, content and matters to be taken into account in a management plan

The purpose of this Management Plan is to describe the philosophy and direction of management for the Park for the next seven years in accordance with the EPBC Act. The Plan enables management to proceed in an orderly way; it helps reconcile competing interests and identifies priorities for the allocation of available resources.

Under s.367(1) of the EPBC Act, a management plan for a Commonwealth reserve (in this case, the Park) must provide for the protection and conservation of the reserve. In particular, the Plan must:

(a) assign the reserve to an IUCN protected area category (whether or not a Proclamation has assigned the reserve or a zone of the reserve to that IUCN category); and

(b) state how the reserve, or each zone of the reserve, is to be managed; and

(c) state how the natural features of the reserve, or of each zone of the reserve, are to be protected and conserved; and

(d) if the Director holds land or seabed included in the reserve under lease—be consistent with the Director’s obligations under the lease; and

(e) specify any limitation or prohibition on the exercise of a power, or performance of a function, under the EPBC Act in or in relation to the reserve; and

(f) specify any mining operation, major excavation or other works that maybe carried on in the reserve, and the conditions under which it may be carried on; and

(g) specify any other operation or activity that may be carried on in the reserve; and

(h) indicate generally the activities that are to be prohibited or regulated in the reserve, and the means of prohibiting or regulating them; and

(i) indicate how the Plan takes account of Australia’s obligations under each agreement with one or more other countries that is relevant to the reserve (including the World Heritage Convention and the Ramsar Convention, if appropriate)

(j) if the reserve includes a National Heritage place:

(i) not be inconsistent with the National Heritage management principles; and

(ii) address the matters prescribed by regulations made for the purposes of paragraph 324S(4)(a); and

(k) if the reserve includes a Commonwealth Heritage place:

(i) not be inconsistent with the Commonwealth Heritage management principles; and

(ii) address the matters prescribed by regulations made for the purposes of paragraph 341S(4)(a).

In preparing a management plan the EPBC Act (s.368) also requires account to be taken of various matters. In respect to Kakadu National Park these matters include:

the regulation of the use of the Park for the purpose for which it was declared

- the traditional owners of the Park

- any other Indigenous persons interested in the Park

- any person who has a usage right relating to land, sea or seabed in the Park that existed (or is derived from a usage right that existed) immediately before the Park was declared

the protection of the special features of the Park, including objects and sites of biological, historical, palaeontological, archaeological, geological and geographical interest

2.6 IUCN category and zoning

A management plan must assign a Commonwealth reserve to one of the following IUCN protected area categories (which correspond to the categories of protected areas identified by the IUCN):

A management plan may divide a Commonwealth reserve into zones and assign each zone to an IUCN category. The category to which a zone is assigned may differ from the category to which the reserve is assigned (s.367(2)).

The provisions of a management plan must not be inconsistent with the management principles for the IUCN category to which the reserve or a zone of the reserve is assigned (s.367(3)). See Section 3 for information on Kakadu’s IUCN category.

2.7 Lease agreements

As noted in Section 2.4, at the time of preparing this Plan approximately 50 per cent of the land within Kakadu National Park is Aboriginal land under the Land Rights Act leased to the Director by Aboriginal land trusts. Section 367(1)(d) of the EPBC Act requires that the Plan must be consistent with the lease agreements (see Section 2.5).

Most of the land in Stage One of the Park is leased by the Director from the Kakadu Aboriginal Land Trust, three areas in Stage Two are leased from the Jabiluka Aboriginal Land Trust, and approximately half of Stage Three is leased from the Gunlom Aboriginal Land Trust.

The lease agreements reserve the right of Aboriginals to enter and use the leased land in accordance with Aboriginal tradition and outline the Director’s obligations in regards to the management of Aboriginal land declared under the Land Rights Act.

The lease agreement with the Gunlom Aboriginal Land Trust includes special provisions about managing and protecting sacred sites, particularly the Sickness Country, rehabilitation of old mine workings in the Gunlom Land Trust area, and control of Aboriginal cultural material.

The full provisions of the leases at the time of preparation of this Plan are included as Appendix A to this Management Plan.

Section 4.1 Making decisions and working together outlines the role of the Northern Land Council under the lease agreements.

2.8 International agreements

This Management Plan must take account of Australia’s obligations under relevant international agreements. The following agreements are relevant to the Park and are taken into account in this Management Plan.

World Heritage Convention

The World Heritage Convention is an international agreement which encourages countries to ensure the protection of their own natural and cultural heritage. The convention’s primary mission is to define and conserve the world’s heritage by drawing up a list of sites whose outstanding values should be preserved for all humanity and to ensure their protection through a closer cooperation among nations. Parties to the convention undertake to identify, protect, conserve, present and transmit to future generations the World Heritage listed sites on their territory.

Stage One of the Park was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1981 and Stage Two in 1987. The whole of the Park was listed in December 1992. Kakadu is one of the few sites that are listed under the World Heritage Convention for both cultural and natural values. Appendix B to this Plan summarises the features of Kakadu that meet the cultural and natural World Heritage criteria.

Convention on Wetlands of International Importance especially as Waterfowl Habitat (Ramsar Convention)

The Ramsar Convention is an international agreement which provides the framework for national action and international cooperation for the conservation and wise use of wetlands and their resources. The convention aims to stop the world from losing wetlands and to conserve, through wise use and management, those that remain. More than 90 countries are contracting parties to the convention.

Sites are selected for the List of Wetlands of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention because of ecological, botanical, zoological, limnological or hydrological importance. Wetlands in Stage One of Kakadu were listed in 1980; wetlands in Stage Two in September 1987; and wetlands in Stage Three that are part of the South Alligator River catchment in 1996. Some 683,000 hectares of Kakadu National Park are included in the Ramsar list.

Australian Ramsar management principles are prescribed by the EPBC Regulations (Schedule 6). An extract from the principles is at Appendix F to this Plan.

In March 1996, the contracting parties to the Ramsar Convention also agreed to establish an East Asian–Australasian Flyway to protect areas used by migratory shorebirds. The flyway provides for an East Asian–Australasian shorebird reserve network of sites that are critically important to migratory shorebirds. The wetlands of Kakadu National Park are part of this reserve network.

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (Bonn Convention)

The Bonn Convention aims to conserve terrestrial, marine and avian migratory species throughout their range. Parties to this convention work together to conserve migratory species and their habitats. Thirty-nine of the species listed under this convention are found in Kakadu.

CAMBA provides for China and Australia to cooperate in the protection of migratory birds listed in the annex to the agreement and their environment, and requires each country to take appropriate measures to preserve and enhance the environment of migratory birds. Fifty-two species listed under this agreement occur in Kakadu

JAMBA provides for Japan and Australia to cooperate in taking measures for the management and protection of migratory birds, birds in danger of extinction, and the management and protection of their environments, and requires each country to take appropriate measures to preserve and enhance the environment of birds protected under the provisions of the agreement. Forty-nine species listed under this agreement are found in Kakadu.

Appendix E to this Management Plan lists species found in the Park that are listed in or under the Bonn Convention, CAMBA and JAMBA.

3.1 Assigning the Park to an IUCN category

Our aim

The Park is managed in accordance with an IUCN protected area category and relevant management principles to protect Park values while providing for appropriate use.

Background

As noted in Section 2.6, the EPBC Act requires this Management Plan to assign the Park to an IUCN category. The EPBC Regulations prescribe the management principles for each IUCN category. The category to which the Park is assigned is guided by the purposes for which the Park was declared (see Section 2.4, Legislative context). The purposes for which Kakadu National Park were declared are consistent with the characteristics for the IUCN protected area category ‘national park’.

What we are going to do

Policy

3.1.1 The Park is assigned to the IUCN Protected Area Category ‘national park’ and will be managed in accordance with the Management Principles set down in Schedule 8 of the EPBC Regulations and listed in Appendix G: