Recovery Plan for the

Grey Nurse Shark (Carcharias taurus)

in Australia

June 2002

Commonwealth of Australia 2001

ISBN 0642547882

This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth, available from Environment Australia. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to:

Assistant Secretary

Marine Conservation Branch

Environment Australia

GPO Box 787

CANBERRA ACT 2601

For additional copies of this publication, please contact the Community Information Unit of Environment Australia on toll free 1800 803 772.

Cover Image

Grey Nurse Shark

Photo Courtesy of David Harasti

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments v

Recovery Team Membership v

List of Abbreviations vi

Summary vii

Part 1. Introduction

1.3 Benefits to Nontarget Species 1

1.4 Social and Economic Impacts of the Plan 2

1.5 Affected Parties 2

1.6 Evaluation and Review 3

2.4.1 Reproductive Biology 5

2.4.2 Young 5

5.3 Recovery Actions and Criteria 30

Part 6. Costs of Recovery

References 40

Appendix A

managed fisheries

Appendix B

Code of Conduct for Diving with Grey Nurse Sharks 45

Tables

Table 1. Legislation to protect Grey Nurse Sharks or identify 1

their status as needing particular conservation action

Table 2. Fisheries that impact or potentially impact on Grey 9

Nurse Sharks

Table 3. Commercial aquaria holdings of Grey Nurse Sharks 16

in Australia

Grey Nurse Shark

Table 5. Numbers of Grey Nurse Sharks observed during NSW 26

Fisheries surveys, 1998-01

Table 6. Summary table of objectives, actions and criteria for 31

the conservation of Grey Nurse Sharks

Table 7. Costs of Recovery Plan Recommendations 37

Maps

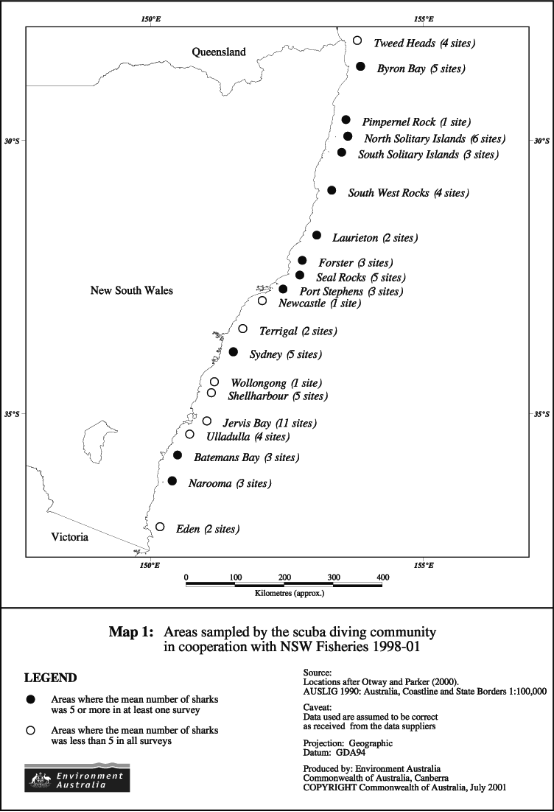

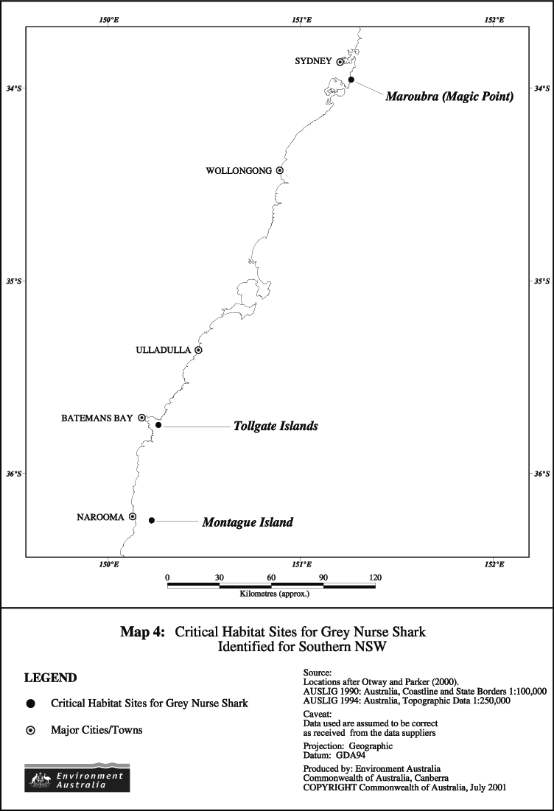

Map 1. Areas sampled by the scuba diving community in 7

cooperation with NSW Fisheries, 1998-01

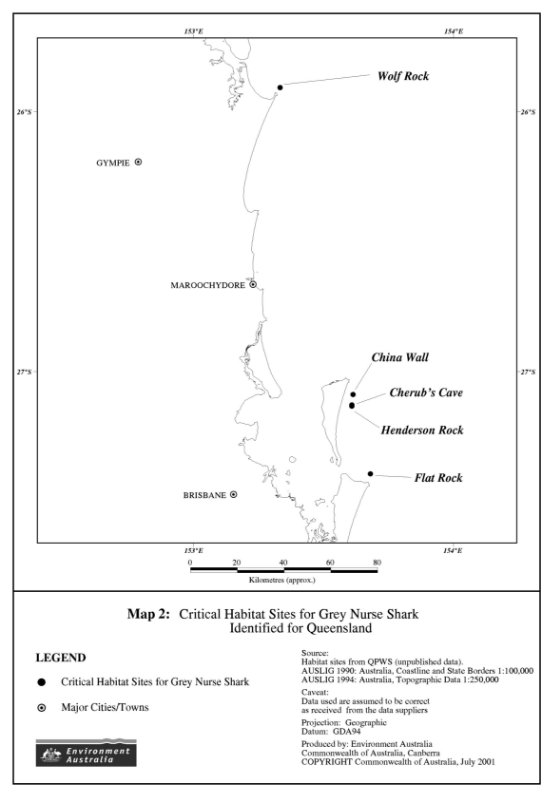

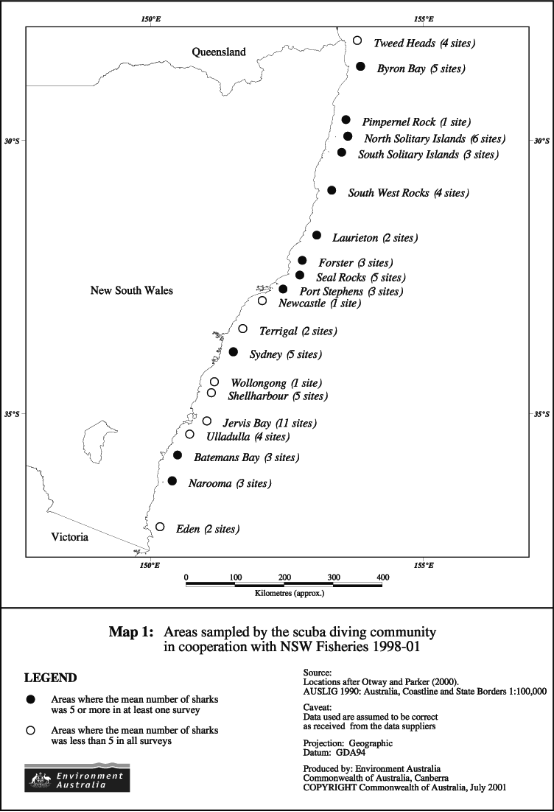

Map 2. Habitat sites critical for the survival of Grey Nurse Shark 22

for Southern Queensland

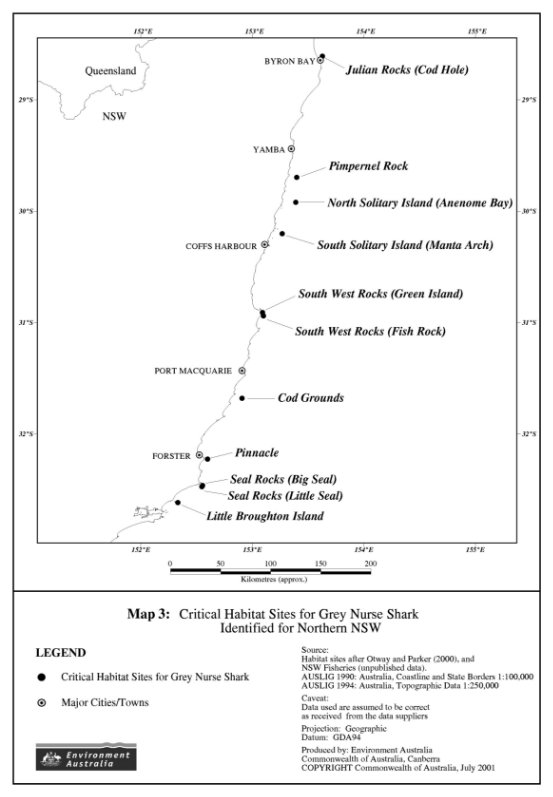

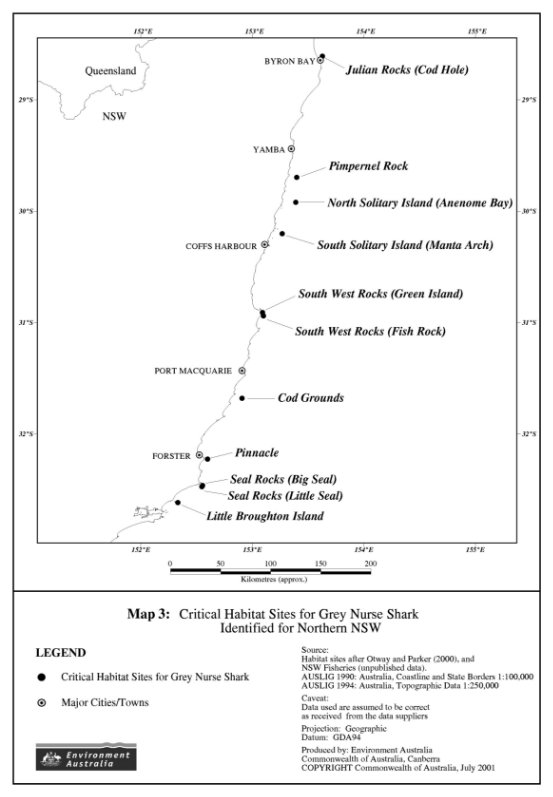

Map 3. Habitat sites critical for the survival of Grey Nurse Shark 23

for Northern New South Wales

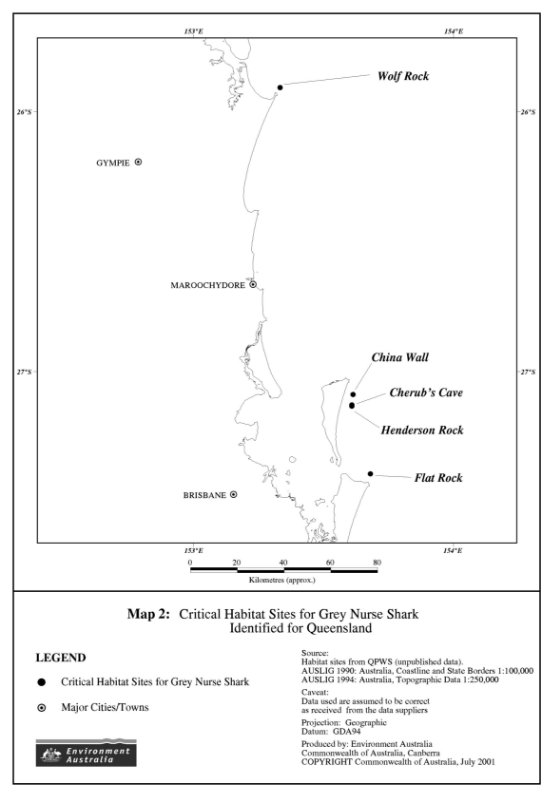

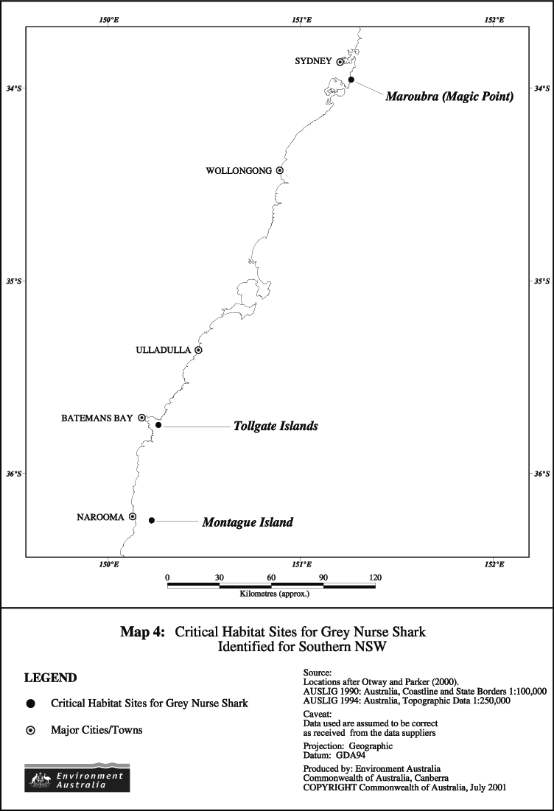

Map 4. Habitat sites critical for the survival of Grey Nurse Shark 24

for Southern New South Wales

Figures

Figure 1. Image of Grey Nurse Shark Carcharias taurus 4

Figure 2. Numbers of Grey Nurse Sharks caught in beach 12

protective shark meshing nets in NSW from 1950-1999

Figure 3. Total catches of Grey Nurse Shark from mesh nets 13

and drumlines - Queensland Shark Control Program

Acknowledgments

Environment Australia would like to thank the members of the Recovery Team, particularly Nick Otway and Dave Pollard for their assistance with the drafts. Members or groups of members and colleagues from within their industries or government sectors have also provided data and advice. Thanks are due to the Queensland Shark Control Program and Western Australia Department of Fisheries for providing data. Thanks also go to staff of Environment Australia, in particular David Harasti, Sara Williams and Sarah Johnstone for all their assistance and advice.

Recovery Team Membership

The list below has been compiled from the two meetings held to discuss and develop the plan. Representation was subject to some changes depending on availability of representatives from various sectors and location and timing of the meetings.

Sara Williams Environment Australia, Marine and Water Division (Chair)

David Harasti Environment Australia, Marine and Water Division

Nicola Beynon Humane Society International

Stephanie Lemm Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service

Geoff McPherson Queensland Department of Primary Industries

Barry Bruce CSIRO Marine Laboratories

John Stevens CSIRO Marine Laboratories

Rory McAuley WA Department of Fisheries

Nick Otway NSW Fisheries

Bill Talbot NSW Fisheries

David Pollard NSW Fisheries

Noel Hitchins Scuba Diving Industry

Ross Monash Recfish Australia

Katrina Maguire Australian Fisheries Management Authority

Joanna Fisher Australian Fisheries Management Authority

Andreas Fischer Aquarium Industry

Craig Bohm Marine and Coastal Community Network

List of Abbreviations

AFFA Agriculture, Fisheries & Forestry - Australia

AFMA Australian Fisheries Management Authority

ANZECC Australia and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council

CALM Department of Conservation and Land Management, Western Australia

CITES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora

COFI Committee on Fisheries

cm centimetres

CSIRO Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation

EA Environment Australia

EPBC Act Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999

ESAC Endangered Species Advisory Committee

ESP Act Endangered Species Protection Act 1992

FAO Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations

IPOA International Plan of Action for Conservation and Management of Sharks

IUCN World conservation Union (formerly International Union for the Conservation of Nature)

km kilometres

m metres

MPAs marine protected areas

NRSMPA National Representative System of Marine Protected Areas

NSW New South Wales

NSW NPWS New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service

PIRSA Primary Industries and Resources South Australia

QDPI Queensland Department of Primary Industries

QFS Queensland Fisheries Service

QPWS Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service

TSSC Threatened Species Scientific Committee

USA United States of America

WA Western Australia

Summary

Current Species Status

The Grey Nurse Shark, Carcharias taurus, is listed as two separate populations under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act 1999). The east coast population is listed as critically endangered and the west coast population is listed as vulnerable under the EPBC Act. The EPBC Act 1999 and EPBC Regulations 2000 (section 7.11) identify the need for preparation of a recovery plan and specifies the content of the plan.

Grey Nurse Sharks are protected under Fisheries Legislation in New South Wales, Western Australia, Victoria, Tasmania and Queensland. The decline of Grey Nurse Shark numbers has been recognised by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which has listed Grey Nurse Sharks as globally vulnerable. They are also fully protected in South Africa, Namibia and Florida (USA).

Habitat and Distribution

Grey Nurse Sharks are often observed just above the sea bed in or near deep sandy-bottomed gutters or rocky caves in the vicinity of inshore rocky reefs and islands. The diet of the adult Grey Nurse Shark consists of a wide range of bony fishes such as jewfish and kingfish, other sharks and rays, squids, crabs and lobsters.

Grey Nurse Sharks have a broad inshore distribution, primarily in sub-tropical to cool temperate waters around the main continental landmasses. In Australia, Grey Nurse Sharks have been regularly reported from Mooloolaba in southern Queensland around most of the southern half of the continent (excluding the Great Australian Bight), and northward to Shark Bay in Western Australia. The Grey Nurse Shark has been recorded as far north as Cairns in the east, the North West Shelf in the west, and also in the Arafura Sea. The distribution of Grey Nurse Sharks is now confined to coastal waters off southern Queensland, the entire New South Wales coast and the south-west coastal waters of Western Australia.

Threats

Historically, due to their fierce appearance and being mistaken for other sharks that pose a danger to humans, large numbers of Grey Nurse Sharks were killed by recreational spear and line fishers and in shark control programs, particularly in south-eastern Australia. Major threats to the recovery of Grey Nurse Sharks include:

- incidental capture by commercial and recreational fisheries;

- shark control activities;

- shark finning; and

- ecotourism.

The life history characteristics of Grey Nurse Sharks have left the remaining populations vulnerable to any small scale changes, and populations in NSW waters have not recovered since their protection in 1984. The total number of individuals on the east coast of Australia is low and estimated to be less than 500 individuals. The number of Grey Nurse Sharks in NSW could be as low as 292; the highest number of individuals observed during a single survey period at all sites where these sharks are currently known to occur in NSW. There are concerns that this population has fallen to such critically low numbers that individual animals are now failing to find mates and successfully reproduce. In addition, fishing activity, particularly recreational line fishing are thought to be impacting severely on the existing Grey Nurse Shark population.

Biodiversity Benefits

The benefits to biodiversity of the actions identified in this plan will be varied. Some benefits to other marine species can be immediately identified, such as:

- the effective management of bycatch in fisheries;

- the effective management of bycatch in shark control activities;

- the protection of marine habitat; and

- the additional protection for other threatened marine species.

Recovery Team Membership

Representation on the Recovery Team was drawn from a cross-section of affected and interested parties, including government departments, non-government organisations and people involved in or interested in shark conservation and management.

Recovery Objectives

The overall recovery objective is:

To increase Grey Nurse Shark numbers in Australian waters to a level that will see the species removed from the schedules of the EPBC Act.

The specific objectives are to:

- Reduce the impact of commercial fishing on Grey Nurse Sharks.

- Reduce the impact of recreational fishing on Grey Nurse Sharks.

- Reduce the impact of shark finning on Grey Nurse Sharks.

- Reduce the impact of shark control activities on Grey Nurse Sharks.

- Manage the impact of ecotourism on Grey Nurse Sharks.

- Eliminate the impact of aquaria on Grey Nurse Sharks.

- Identify and establish conservation areas to protect Grey Nurse Sharks from threatening activities such as commercial and recreational fishing.

- Develop research programs to assist conservation of Grey Nurse Sharks.

- Develop population models to assess Grey Nurse Shark populations and monitor their recovery.

- Promote community education about Grey Nurse Sharks.

- Develop a quantitative framework to assess the recovery of the species.

Actions and Recovery Criteria

To fulfil the specific objectives of this plan, actions are designed to identify and reduce the threats to Grey Nurse Sharks, determine levels of mortality and reduce that mortality. The assessment of the actions against the criteria for success is essential to measure the recovery of Grey Nurse Sharks. These actions and criteria can be found in Table 6 and are summarised as:

- assess commercial and recreational fisheries data to determine current levels of Grey Nurse Shark bycatch;

- modify fisheries logbooks to permit recording of Grey Nurse Shark catch and biological data;

- ensure existing fishery observer programs record interactions with Grey Nurse Sharks;

- prevent unregulated shark finning;

- quantify and reduce levels of Grey Nurse Shark take in shark control activities;

- minimise ecotourism and aquaria impacts on Grey Nurse Sharks;

- develop appropriate mechanisms to protect habitat critical for the survival of Grey Nurse Sharks;

- establish community based programs to identify and monitor key sites for Grey Nurse Sharks;

- collect biological and genetic information to assess the population size and status of Grey Nurse Sharks; and

- develop a community education strategy for Grey Nurse Sharks.

Evaluation and Review

The life of the recovery plan is 5 years. The EPBC Act states the need to evaluate the performance of the plan. A review will be carried out annually by the recovery team. The recovery team will also undertake an evaluation of the plan within 5 years.

Part 1. Introduction

1.1 Conservation Status

The Grey Nurse Shark, Carcharias taurus (Rafinesque 1810), is listed as two separate populations under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). The east coast population is listed as critically endangered and the west coast population is listed as vulnerable. This species became the first protected shark in the world when the NSW Government declared it a protected species in 1984 (Pollard et al. 1996). Grey Nurse Sharks are now protected under fisheries legislation in New South Wales, Western Australia, Victoria, Tasmania and Queensland and is listed as vulnerable globally on the IUCN Red List of Threatened species 2000 (Table 1).

Until recently the Grey Nurse Shark had an undeserved reputation in Australia as a man-eater. Harding (1990) and many others before him, found that the species is not a threat to divers or swimmers unless provoked. Many shark attacks in Australia have been attributed incorrectly to the Grey Nurse Shark (Whitley 1983), often due to its fierce appearance. The Grey Nurse Shark's reputation led to indiscriminate killing of the species by spear and line fishers (Last & Stevens 1994). During the 1950s and 60s there was a concerted effort among spear fishers to wipe out Grey Nurse Sharks along the NSW coastline (Cropp 1964, Ireland 1984). Cropp (1974) speculated that at the time of publication, close to 300 Grey Nurse Sharks had been taken since the use of powerheads became widespread in skin diving circles. He also reported taking 24 grey nurse from a single gutter at Seal Rocks and earlier reflected that the Grey Nurse Shark would soon become rare as a consequence of the introduction of powerheads (Cropp 1974).

Current threats to the species are believed to be incidental catch by recreational fishing and various commercial fisheries (such as NSW Ocean Trap and Line and WA Shark Gillnet Fisheries), and to a much lesser extent protective beach meshing (Pollard et al. 1996, Krogh 1994, and Pepperell et al. 1993).

Table 1. Current legislation to protect Grey Nurse Sharks or identify their conservation status.

Jurisdiction | Legislation | Status |

Queensland | | Protected |

Western Australia | Wildlife Conservation Act 1950 | Protected |

Tasmania | Fisheries Regulations 1996 (General and Fees) Amendment Regulations 1988 | Protected |

Victoria | Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 | Protected |

NSW | Fisheries Management Act 1994 and 1997 Amendments | Endangered |

Commonwealth west coast Population | Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 | Vulnerable |

Commonwealth east coast Population | Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 | Critically Endangered |

1.2 Reasons for Listing

The Grey Nurse Shark was listed as vulnerable on the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 in August 2000. This listing was based on declining population trends, the life history characteristics of the species, limited knowledge of their ecology and abundance, and the fact that Grey Nurse Sharks were still under pressure from some sectors of the Australian commercial and recreational fishing industries.

Recently however, (October 2001) the Grey Nurse Shark was listed as two separate populations under the EPBC Act. Given the serious decline in numbers of the east coast population of Grey Nurse Sharks, this population is now listed as critically endangered. The size of the west coast population is unknown but considering the species life history characteristics and continuing impacts from fishing, this population remains listed as vulnerable under the EPBC Act.

Prior to national listing, Grey Nurse Sharks were protected in NSW in 1984. The species is known to be migratory and the protection provided by NSW becomes ineffective when a shark crosses a state boundary (Environmental Protection Authority 1996). This was another contributing factor that supported the national listing of Grey Nurse Sharks.

1.3 Benefits to Nontarget Species

Section 270 (2)(h) of the EPBC Act indicates the need to identify the activities in this recovery plan that will benefit species other than Grey Nurse Sharks. Conservation measures to benefit Grey Nurse Sharks and their habitat will also benefit threatened marine species and inshore marine communities. By managing fishery bycatch and researching alternatives to beach protective shark nets, other species, such as whales, dolphins, marine turtles, pelagic rays, some fish species and other sharks that pose no threat to beach users, will be less subject to these sources of mortality. Some of these species are also threatened or uncommon with limited information available about their ecology.

1.4 Social and Economic Impacts of the Plan

Section 270 (3)(c) of the EPBC Act states that there is a need to minimise any significant adverse social and economic impacts in the development of recovery plans. Objectives and actions in this plan have been formulated with this in mind. Responsibility for the actions identified in this plan lie mostly with Commonwealth and State Governments. Various sectors of the fishing industry may be impacted through the need to quantify grey nurse bycatch and any subsequent actions such as the declaration of marine protected areas that may exclude fishing activities. Further management action may be required to reduce the impact on commercial, recreational and spearfishing interests.

There will be some impact on scuba divers due to educative programs, Grey Nurse Shark survey work and possible restrictions on diving with Grey Nurse Sharks at known aggregation sites. Aquaria will also be impacted through a national moratorium on the taking of Grey Nurse Sharks from the wild, the development of management plans for the keeping of Grey Nurse Sharks and the development of Grey Nurse Shark education programs.

1.5 Affected Parties

Section 270 (2)(g)(i) of the EPBC Act indicates the need to identify organisations likely to be affected by the actions proposed in this plan. The list below is not exhaustive and includes organisations represented on the Recovery Team.

Commonwealth

Department of the Environment and Heritage

Australian Fisheries Management Authority

Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry - Australia

State/Territory/Local Government

Department of Primary Industries and Resources South Australia

Department of Conservation and Land Management, Western Australia

Fisheries Western Australia

Fisheries Victoria, Department of Natural Resources and Environment

New South Wales Fisheries

New South Wales Marine Parks Authority

New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service

Queensland Fisheries Service - Queensland Department of Primary Industries

Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service

Non Government Organisations

Commercial fishers

Recreational fishers

Conservation and wildlife interest groups

Dive clubs

Aquaria

Scuba diving schools

1.6 Evaluation and Review

Section 270 (2)(g)(ii) of the EPBC Act states the need to identify who will evaluate the performance of the plan. An annual review will be carried out by the Grey Nurse Shark Recovery Team and a report of that review will be forwarded to the Threatened Species Scientific Committee (TSSC). Section 279(2) of the EPBC Act also identifies that an evaluation of the plan will be undertaken at intervals of not longer than five years. The Recovery Team will carry out the evaluation with the outcome being a report to the Minister for the Environment and Heritage.

The recovery plan may be varied at any time on the request of the Minister (EPBC Act Section 279). Such a request may occur if information that significantly alters the actions identified in the plan is revealed.

Part 2. Biological Description

2.1 Description of Species

The Grey Nurse Shark, Carcharias taurus (Rafinesque, 1810), also known in the USA as the sand tiger shark and in South Africa as the spotted ragged-tooth shark, is one of four species belonging to the family Odontaspididae (Pollard et al. 1996). The species has a large, rather stout body and is coloured grey to grey-brown dorsally, with a paler off white under belly (Last & Stevens 1994). Reddish or brownish spots may occur on the caudal fin and posterior half of the body, particularly in juveniles (Last & Stevens 1994; Pollard et al. 1996). The species has a conical snout, long awl-like teeth in both jaws (with single lateral cusplets), similarly sized first and second dorsal fins and an asymmetrical caudal fin (Last & Stevens 1994; Pollard et al. 1996). Grey Nurse Sharks grow to at least 360 cm total length (Last & Stevens 1994). The Grey Nurse Shark is a slow but strong swimmer and is thought to be more active at night (Pollard et al. 1996).

Figure 1: Grey Nurse Shark, Carcharias taurus (From: Last and Stevens, 1994)

2.2 Distribution

Grey Nurse Sharks have a broad inshore distribution, primarily in sub-tropical to cool temperate waters around the main continental landmasses, except in the eastern Pacific Ocean off north and south America (Last and Stevens 1994).

In Australia, Grey Nurse Sharks have been regularly reported from Mooloolaba in southern Queensland around most of the southern half of the continent, although the species is uncommon in Victorian, South Australian and Tasmanian waters, and has not been found in the Great Australian Bight. The Grey Nurse Shark has been recorded as far north as Cairns in the east, the North West Shelf in the west and the Arafura Sea in the north (Stevens 1999, Pogonoski et al. 2001). However, more recently Grey Nurse Shark distribution in Australia has generally been confined to coastal waters off southern Queensland and along the entire NSW coast, and in Western Australia, predominantly the coastal waters of the southwest.

In NSW, aggregations of Grey Nurse Sharks can be found at reefs off the following locations: Byron Bay, Brooms Head, Solitary Islands, South West Rocks, Laurieton, Forster, Seal Rocks, Port Stephens, Sydney, Bateman's Bay and Narooma (Otway and Parker 2000) (see Map 1). An aggregation is considered to be 5 or more Grey Nurse Sharks present at the same site at the same time (Otway and Parker 2000). Known key aggregation sites for Grey Nurse Sharks in Queensland include sites off Moreton and Stradbroke Islands and Rainbow Beach. The above sites may play an important role in pupping and/or mating activities, as Grey Nurse Sharks form regular aggregations at these sites (Pollard et al. 1996).

Relatively little is known about the migratory habits of Grey Nurse Sharks in Australian waters. Evidence suggests migrational movement, probably in response to water temperatures, up and down the east coast. At certain times of the year Grey Nurse Sharks aggregate according to sex. Male animals predominate southern Queensland waters during July to October, while a high proportion (77.4 per cent) of the catch from beach meshing operations off central NSW at the same time of year is composed of females (Reid and Krogh 1992).

Dive charter operators regularly see Grey Nurse Sharks at the same locations and these observations suggest that the species exhibits some degree of site fidelity (Pollard et al. 1996). This characteristic makes the species vulnerable to localised pressures in certain areas (Environment Australia 1997).

2.3 Habitat and Diet

Grey Nurse Sharks are often observed hovering motionless just above the seabed, in or near deep sandy-bottomed gutters or rocky caves, and in the vicinity of inshore rocky reefs and islands (Pollard et al. 1996). The species has been recorded at varying depths, but is generally found between 15 m and 40 m (Otway and Parker 2000). Grey Nurse Sharks have also been recorded in the surf zone, around coral reefs, and to depths of around 200 metres on the continental shelf (Pollard et al. 1996). They generally occur either alone or in small to medium sized groups, usually of fewer than twenty sharks (Pollard et al 1996). Those Grey Nurse Sharks that are observed alone are thought to be moving between aggregation sites. Recent NSW Fisheries survey data indicates that a group of 20 sharks or more would be a notable event.

The diet of the adult Grey Nurse Shark consists of a wide range of fish, other sharks and rays, squids, crabs and lobsters (Compagno 1984). In Australia it is likely that the Grey Nurse Shark diet consists of species such as pilchards, jewfish, tailor, bonito, moray eels, wrasses, sea mullet, flatheads, yellowtail kingfish, small sharks, squid and crustaceans (N. Otway pers. comm.). Observations also suggest that schools of Grey Nurse Sharks can feed cooperatively by concentrating schooling prey before feeding on them (Compagno 1984; Ireland 1984). It is important to note that many of the species that comprise the Grey Nurse Sharks diet are also harvested by commercial, recreational and spearfishing interests.

2.4 Life History

There is limited information available on the biology of the Grey Nurse Shark in Australian waters, mostly limited to catch records from beach protective shark meshing and popular accounts in diving and fishing magazines (Pollard et al.1996). The life history characteristics (detailed below) of Grey Nurse Sharks make them particularly vulnerable to over-exploitation (Pollard et al. 1996).

2.4.1 Reproductive Biology

The Grey Nurse Shark has a relatively low growth rate and take 4 - 6 years to mature (Branstetter & Musick 1994), with both males and females maturing at about 220cm total length (Last & Stevens 1994). The precise timing of mating and pupping in Australian waters is unknown. Many sharks have been observed at Pimpernel Rock, NSW (see Map 1) during the months of March and April with mating scars, ie. bite marks around the pectoral fins and head area (D. White pers. comm. in Otway and Parker 1999). In South Africa mating occurs between late October and the end of November, with pregnant females moving southwards each year during July and August to give birth in early spring, then returning northward. Once impregnated, the female stores the sperm while the ovaries produce eggs that move to the oviduct where they are fertilised (Marsh 1995). Not all migrating females are sexually active and generally only reproduce once every two years (Smith and Pollard 1999).

The reproductive norm for the Grey Nurse Shark includes oophagy and intra-uterine cannibalism which results in a maximum of two young per litter (one in each uterus). Embryos hatch into the uterus at about 55 mm long and at lengths of around 10 cm they develop teeth and consume other embryos in the uterus. The single remaining embryo in each uterus then feeds on any unfertilised eggs as the female continues to ovulate. Gestation takes 9-12 months (Last & Stevens 1994).

2.4.2 Young

At birth the Grey Nurse Shark pups measure on average 1 metre in length (Last & Stevens 1994). In Australia it appears that these sharks give birth at select pupping grounds. In July 2001 the first recorded birth of a Grey Nurse Shark was observed, one pup was born in the late morning at Julian Rocks Byron Bay (N. Otway pers. comm.).

2.4.3 Longevity

A Grey Nurse Shark held in captivity at a Sydney aquarium lived for 13 years, and others have lived for over 16 years in captivity in South Africa (Govender et al. 1991). The average life span of this species in the wild is unknown, although it is likely that larger specimens in the wild may be much older than 13 or 16 years (Pollard et al. 1996).

2.5 Degree of Decline

Grey Nurse Shark numbers are believed to be in decline in NSW based on recent NSW Fisheries surveys (Otway and Parker 2000), measures of relative abundance, catch records of protective shark meshing and anecdotal reports. The number of Grey Nurse Sharks in NSW could be as low as 292 (NSW Fisheries survey seven: March - June 2000). This is the highest number of individuals observed during a single survey (four week) period (NSW Fisheries unpublished data). Map One illustrates the survey sites along the NSW coast. There are now concerns that the east coast population has fallen to such critical numbers that individual animals may now be failing to find mates and successfully reproduce.

A decline in Grey Nurse Shark numbers is also evident from beach meshing figures, which need to be considered in the context of the increase in meshing effort since the 1950s. In NSW, the number of Grey Nurse Sharks caught has declined from 58 between October and December 1937 (Coppleson 1962), to a total of only 65 caught between October 1972 and December 1990 (Krogh and Reid 1996, see also Figure 2). In the first two years of shark netting in Queensland (1962/63), a total of 35 Grey Nurse Sharks were caught, while only 27 were caught between 1985 and 1999 (Shark Control Program, QDPI).

In 1984 the Grey Nurse Shark was afforded protected status in NSW and became the first shark species in the world to become protected. Population numbers in NSW have apparently failed to respond to the statewide protection established in 1984 (Otway and Parker 2000). Anecdotal evidence suggests a dramatic decline in the number of Grey Nurse Sharks along Sydney’s coastline and at known aggregation sites such as Seal Rocks (Pollard et al. 1996). Many areas along the NSW coastline, such as Brush Island just south of Ulladulla, no longer support populations of Grey Nurse Sharks (D. Harasti pers. comm., Otway and Parker 2000).

Very little is known about the conservation status of Grey Nurse Sharks in Western Australia. It appears that the Grey Nurse Shark population of Western Australia may be larger than originally thought; however, at these catch rates it is inevitable that this population will also decline considering their life history characteristics (Pogonoski et al. 2001).

Part 3. Threats

There are a number of suggested causes for the observed decline in Grey Nurse Shark numbers. The most identifiable of these is spearfishing (historically), the incidental capture in south-eastern Australia commercial fisheries, recreational fishing and protective beachmeshing (Pollard et al. 1996, Krogh 1994, Otway and Parker 2000).

3.1 Commercial Fishing

Although currently protected in most states, Grey Nurse Sharks have been fished commercially in the past. The Grey Nurse Shark was the second most commonly caught shark after the whaler shark around Port Stephens in the 1920s (Roughley 1955). The Grey Nurse Shark was fished by hook and line in and around Botany Bay as early as the 1850s, to provide an excellent quality oil for burning in lamps (Grant 1987). Grey Nurse Sharks were also utilised for their fins and for the high quality leather that could be produced from their skin (Roughley 1955). Grey Nurse Shark meat has been utilised fresh, frozen, smoked, dried and salted for human consumption, especially in Japan (Compagno 1984).

In spite of legislative protection Grey Nurse Sharks are still under threat from incidental catch in some commercial fisheries. In Australia they are primarily caught by demersal nets, droplines, and other line fishing gear (Pollard et al. 1996). Recent anecdotal information indicates that Grey Nurse Sharks have been incidentally caught on bottom setlines targeting wobbegong sharks (Otway and Parker 2000). Professional fishers once avoided the rocky habitats where Grey Nurse Sharks congregate but with improved technology (such as Geographical Positioning Systems) they are able to navigate more accurately and fish closer to these areas. There are very few records of Grey Nurse Sharks being caught in Commonwealth managed fisheries (see Appendix A).

The extent of the impact that commercial fisheries currently have on Grey Nurse Sharks needs to be documented. Not all industry participants share the perception that bycatch levels of Grey Nurse Sharks are a threat to their populations. Views may differ because the recording and recognition of Grey Nurse Sharks may be poor, or because interactions are now so infrequent due to population decline. It is necessary to identify which fisheries are impacting on Grey Nurse Sharks and to quantify the level of their bycatch. This could initially be assessed by ensuring that fishery logbooks allow for the recording of Grey Nurse Shark interactions, that fishers are educated on Grey Nurse Sharks and that observer programs are introduced to State commercial fisheries.

Table 2. Commercial fisheries that impact or potentially impact on Grey Nurse Sharks.

Jurisdiction | Fishery |

NSW | Ocean Trap and Line |

NSW | Ocean Fish Trawl |

NSW | Ocean Prawn Trawl |

Queensland | East Coast Trawl |

Queensland | Queensland Line Fisheries |

Western Australia | Northern Shark Fishery |

Western Australia | West Coast Demersal Gillnet and Demersal Longline Fishery |

Western Australia | Southern Demersal Gillnet and Demersal Longline Fishery |

In NSW fishers that incidentally catch Grey Nurse Sharks must release them if still alive. As a consequence sharks are often seen with hook and line trailing from their mouths while others have been observed entangled in fishing gear (Environment Australia 1997). NSW survey reports indicate that approximately 6% of Grey Nurse Sharks sighted show signs of having had interactions with fishing gear (Otway and Parker 2000).

The Grey Nurse Shark is caught as a bycatch in WA commercial shark fisheries. 52.3t (live wet weight) of Grey Nurse Sharks were caught in the Joint Authority Demersal Gillnet & Demersal Longline Fishery (JASDGDLF) and the West Coast Demersal Gillnet & Demersal Longline Fishery (WCDGDLF) between 1985 and 2000 (R. McAuley pers. comm.). In addition it is estimated that 6.6t of Grey Nurse Sharks were taken as bycatch in the WA Northern Shark Fishery in 1996 (Stevens 1999). This northern WA data may not be entirely accurate as there are some problems with identifying vessels licensed to operate in this fishery and there is likely to be some mis-identification of the species.' (R. McAuley pers. comm.). Even though the species became protected in WA in 1997, it is most likely still caught as bycatch in the commercial shark fisheries.

Hook wounds to Grey Nurse Sharks can puncture the stomach, pericardial cavity, and oesophagus causing infections and death. A hooked shark, upon release, may swim away seemingly unharmed, only to die several days later from internal bleeding or peritonitis. The stress of capture may cause changes in the physiology of a shark including bradycardia, blood acidosis, hyperglycaemia and muscle rigidity.

Management Responses

The primary response required to the impact of commercial fishing on the critically endangered east coast population is habitat protection. This response is further discussed in Section 4.1 of the recovery plan.

The taking of Grey Nurse Sharks in Commonwealth waters is prohibited under the EPBC Act. Those commercial fishers that operate where there is a risk of capture of Grey Nurse Sharks in Commonwealth waters could be in breach of the Act and therefore subject to prosecution. The preferred method of dealing with the bycatch of Grey Nurse Sharks in Commonwealth waters is through the accreditation of fishery management arrangements under Section 208A of the EPBC Act. This allows for the assessment of the fishery to ensure that all reasonable efforts are required as part of the management arrangements to avoid killing or injuring listed species and that the result of any take will not adversely affect the survival or recovery of species in the wild.

Under the EPBC Act, commercial fishers that capture a Grey Nurse Shark in Commonwealth waters must report it to the Secretary for the Commonwealth Department of Environment and Heritage. There have been no reports to date and this could possibly be due to lack of knowledge of this requirement, identification problems and that the catch of Grey Nurse Sharks in Commonwealth waters has been minimal.

Issues

- It is currently not clear which commercial fisheries impact on Grey Nurse Sharks.

- The mortality of Grey Nurse Sharks in all commercial fisheries bycatch has not been quantified.

- There is a need to improve reporting of listed marine species taken in Commonwealth & State fisheries.

- Person(s) that injure or kill a Grey Nurse Shark from the east coast population could be prosecuted under Part 3 Section 18 of the EPBC Act.

- There is a need for fisheries that impact on Grey Nurse Sharks to take all reasonable action to minimise that take.

Prescribed Actions

A.1 - A.8 (see table 6)

3.2 Recreational Fishing

Recreational fishing covers a broad range of amateur fishing activities but can be roughly broken down into groups of gamefishers, sportfishers, spearfishers, estuarine fishers and freshwater fishers. In respect to Grey Nurse Sharks, spearfishers, gamefishers and sportfishers are discussed in this plan.

Spearfishers

As late as the 1980s, Grey Nurse Sharks were perceived by the public as man-eaters, mainly due to their fierce appearance (Taronga Zoo 1996). This misunderstanding led to many Grey Nurse Sharks being killed in the 1950s and 1960s by the intensive fishing efforts of spearfishers using powerheads (Ireland 1984). The Grey Nurse Shark, with its dubious reputation as a threat to humans, was an easy target and many articles recount the desire of the spearfishers to rid the coast of this threat (Cropp 1964a; Ley 1964; Lupton 1962; Taylor and Cropp 1962).

One of the possible explanations for Grey Nurse Sharks being more abundant in Western Australia waters is that they were never subject to the spearfishing pressure during the 1950s and 60s that the New South Wales and Queensland population encountered. Today, due to the Grey Nurse Shark's protected status in NSW since 1984, and an increase in public awareness, there are very few reports of divers killing these sharks (Pollard et al. 1996). In fact, many spearfishers and divers have been involved in conservation activities including the protection of Grey Nurse Sharks and survey work on the species (refer to 4.4 - Community Involvement section).

Gamefishers

Grey Nurse Sharks are known to be poor fighters and are no longer favoured by gamefishers in comparison to other sharks (Bureau of Resource Sciences 1996). However, during the two decades from 1961 to 1980, 405 Grey Nurse Sharks were recorded as being taken by game fishing clubs on the NSW coast, from Bermagui northwards along some 460km of coastline (Pepperell 1992). A decline was detected in the proportion of Grey Nurse Sharks caught by gamefishers in the 1960s and 1970s (Environment Australia 1997), and recreational gamefishers voluntarily banned Grey Nurse Shark captures in 1979 (Marsh 1995).

Sportfishers

Sportfishers range from individuals to groups fishing in middle sized boats and charter boats. The extent of the impact that incidental catch by sportfishers has on Grey Nurse Sharks is currently unknown. Most recreational fishers say it as a “minimal problem”, but it is necessary to assess the level of incidental catch, particularly of juvenile sharks, by these fishers. Recreational fishers that line fish with baited hooks in known aggregation areas are likely to hook a Grey Nurse Shark

There have been various reports of recreational fishers catching Grey Nurse Sharks. Aggregation sites such as Fish Rock off South West Rocks and the Pinnacle at Forster are often under pressure from recreational fishing. In July 2001, scuba divers observed that over 50% of the Grey Nurse Sharks at Fish Rock (off South West Rocks, NSW) had hooks and lines trailing from their mouths (D. Harasti pers. comm.). It is believed that the hooks and line were from recreational fishing gear. Whilst the latter observations are based on individuals that survive these interactions, it is not known how many die as a result of these interactions. Recreational fishers have been observed fishing on top of the Grey Nurse Shark gutters at Fish Rock and divers have actually observed Grey Nurse Sharks taking the baited hooks of recreational fishers. Other sites where recreational fishers have been observed catching Grey Nurse Sharks include the Cod Grounds off Laurieton, Pimpernel Rock in the Solitary Islands Marine Reserve and Montague Island off Narooma.

In a recent autopsy carried out on a Grey Nurse Shark that died in captivity, the cause of death was attributed to peritonitis arising from perforation of the stomach wall by numerous small hooks of the type used by recreational fishers (Otway and Parker 2000).

The incidental catch by recreational fishers is expected to have been high on the east coast in the past given the estimates of the low numbers now present. It has been hypothesised by the Recovery Team that recreational fishers may be responsible for higher levels of Grey Nurse Shark mortality than previously realised. The NSW Fisheries Grey Nurse Shark surveys have found that the observed numbers of juveniles is much lower than expected indicating that this problem may be continuing. It is suspected that recreational fishers often kill juvenile Grey Nurse Sharks without realising the species identity.

Management Responses

It is obviously necessary to protect key Grey Nurse Shark areas from the risk of incidental catch. This protection should include establishment of effective marine protected areas and seasonal or permanent closure to commercial and recreational fishers for these important sites (refer to Section 4.1 Habitat Protection).

As a consequence of listing under the EPBC Act 1999, if a recreational fisher carries out activities that result in the taking of a listed species in Commonwealth waters, it must be reported to the Secretary for the Commonwealth Department of Environment and Heritage. Reporting to date has been poor, possibly due to the lack of knowledge of this requirement and possible identification problems.

With the low number of animals of this species on the east coast and their slow reproductive rate, any killing, taking or injuring a Grey Nurse Shark would be likely to have a significant impact on the population. Under Part 3 Section 18 of the EPBC Act:

A person must not take an action that:

(a) has or will have a significant impact on a listed threatened species included in the critically endangered category; or

(b) is likely to have a significant impact on a listed threatened species included in the critically endangered category.

Civil penalty:

(a) for an individual—5,000 penalty units;

(b) for a body corporate—50,000 penalty units.

Therefore, any person(s) who injure, take or kill a Grey Nurse Shark in Commonwealth waters, in the east coast where they are listed as critically endangered, will be considered to be impacting on the population and could be subject to civil or criminal prosecution under the EPBC Act 1999. One penalty unit is currently worth $110 Australian dollars.

Issues

- The extent of the impact that incidental catch by recreational fishers has on Grey Nurse Sharks is currently unknown and needs to be urgently addressed.

- There is a need to exclude hook and line fishing from important aggregation areas.

- An education program is needed for recreational fishers about Grey Nurse Shark.

Prescribed Actions

B.1 – B.2 (see table 6)

3.3 Shark Finning

The high market value for shark fins is leading to a level of catch of sharks worldwide that may be unsustainable. As such, the practice of shark finning, where the fins are removed and the carcass discarded, poses a threat to Grey Nurse Sharks. There are a number of reliable reports from NSW divers of sightings of Grey Nurse Sharks that have survived having their fins cut off.

Shark finning has been banned in NSW. It is prohibited in all NSW waters to take and land any shark species mutilated in any manner other than by heading, gutting or removing gills, or for any boat in all NSW waters to possess any detached shark fins on board. An interim ban on the at sea finning of sharks has been implemented in all Commonwealth tuna long line fisheries. Longer term arrangements will be determined through the Australian National Plan of Action for Sharks. Western Australia Department of Fisheries has implemented a similar ban where fishers in WA waters are required to land whole sharks at port before the fins can be removed.

There are however commercial fisheries in Australia that take shark fins as by product. Shark finning is poorly documented in Australian fisheries and several fisheries in Australia target sharks. Approximately 92 tonnes of dried shark fin was exported from Australian fisheries in 1998-99, valued at about $5.5 million. In 1998-99, approximately 7700 tonne of landed shark catch was reported from target shark fisheries. It is estimated that 55.6 tonnes of the 92 tonnes of export dried shark fin in 1998-99 were derived from target and non-target shark fisheries where the trunk is retained. The majority of this shark fin is from the Southern Shark Fishery, managed by the Commonwealth and from the Western Australia's target shark fisheries (AFFA 2001 draft).

Management Responses

The take of protected species for their fins require monitoring. Such monitoring requires a simple system of identification. The monitoring can be addressed through fin x-rays, as fins show cartilaginous patterns unique to each shark species, DNA analysis, or where the physical morphology of the species can be determined because the shark carcass is largely intact.

In 1999, the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) Committee on Fisheries (COFI) agreed to an International Plan of Action for Conservation and Management of Sharks (IPOA-Sharks) as a response to the concern about shark fishing around the world. While the plan is voluntary, all concerned countries are encouraged to implement it by undertaking an assessment of the conservation and management of sharks and prepare a national plan of action if required. The Australian government, led by AFFA, is currently developing a National Plan of Action for Sharks for Australia. This is being undertaken with cooperation of the states and territories.

Issues

- The demand for shark fins is high.

- The targeting of sharks for their fins may be impacting on Grey Nurse Sharks.

Prescribed Actions

C.1 (see table 6)

3.4 Shark Control Activities

Meshing of sharks as a protective measure for swimmers and surfers was introduced to New South Wales beaches in 1937 and to Queensland beaches in 1962. These are the only two states in Australia that employ this shark protection measure (Krogh & Reid 1996; Paterson 1990).

New South Wales

In NSW during the early 1950s, up to 34 Grey Nurse Sharks was meshed each year (Krogh & Reid 1996, Pollard et al. 1996). By the 1980s, this number had decreased to a maximum of 3 or less per year (Pollard et al. 1996), and over the last decade only three Grey Nurse Sharks have been caught in the shark nets (D. Reid. unpublished data). Figure 2 illustrates the decline in numbers of Grey Nurse Shark caught in the NSW shark meshing program over the past fifty years.

Figure 2: Decline in the numbers of Grey Nurse Sharks caught in shark meshing nets in the Newcastle/ Sydney/Wollongong regions from 1950-1999 (Otway and Parker 2000)

Queensland

In Queensland, a mixture of baited drumlines and mesh nets are used. Drumlines consist of a marker buoy and float anchored to the bottom supporting a steel chain and baited hook. There are indications that drumlines are more selective than protective shark meshing nets as they target those species of greatest threat to humans (Department of Primary Industries 1992), while providing similar levels of protection as nets. The disadvantage with the drumlines is that they can move in heavy seas (Department of Primary Industries 1992) and are known to catch other threatened species such as loggerhead turtles (Department of Primary Industries 1998). Mesh nets however also catch non-target species such as turtles and whales. In some situations, drum lines catch as many sharks (if not more) as nets, but the species composition of sharks can vary between the two methods (Department of Primary Industries 1998). Total catches of Grey Nurse Shark in Queensland from net and drumline in all contract areas is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Total catches of Grey Nurse Sharks from mesh nets and drumlines in all contract areas - Queensland Shark Control Program (Courtesy of G. McPherson, Qld Department of Primary Industries)

In Queensland, a similar downward trend as NSW has been detected, with a decrease from 90 Grey Nurse Sharks captured between 1962 and 1972, to 21 Grey Nurse Sharks captured over the last decade. Grey Nurse Sharks are most commonly caught from October to December in the Queensland shark control program (G. McPherson pers. comm.).

While the protective beach meshing program in Qld and NSW has obviously been responsible for captures of numerous Grey Nurse Sharks in the past, the extremely low capture rates in recent years will be likely to continue until the population increases substantially in the coastal waters of Eastern Australia (Otway and Parker 2000).

It is now NSW Fisheries' and the QDPI's Shark Control Program policy that, where possible, all Grey Nurse Sharks caught in these shark nets are transported away from the beaches and released alive. In NSW released sharks will be tagged to assist with scientific studies of population size, growth rates and migratory movements. In NSW Grey Nurse Sharks that die in the nets are to be autopsied and in Queensland they are measured, sexed and their stomach contents examined.

Management Responses

Alternative non lethal methods to beach meshing should be trialed in NSW and Qld. However, the use of any alternative methods would need to be reviewed if they were found to catch more Grey Nurse Sharks. A form of shark control being trialed is the use of electrical fields. Experiments on the use of electrical fields to repel sharks have been carried out in South Africa since 1965 (Cliff and Dudley 1992). However, these trials have encountered many logistical problems (Gribble 1996) and further investigation is required on reports that electrical fields may have detrimental effects on Grey Nurse Sharks that may not be immediately obvious.

By minimising bycatch and researching alternatives to protective shark meshing nets, the Grey Nurse Shark will benefit, particularly if the population increases. Other non-target species that are captured in the shark nets such as whales, dolphins, dugongs, turtles and rays (Gribble et al 1998, Krogh & Reid 1996) would also benefit if protective shark meshing nets were reduced.

Issues

- Shark control activities do impact on Grey Nurse Sharks.

- Beach meshing is non-selective.

- Alternative methods to beach meshing should be trialed.

- Not all Grey Nurse Sharks still alive in shark nets are tagged on release.

Prescribed Actions

D.1 - D.4 (see table 6)

3.5 Ecotourism

Ecotourism activities relevant to the Grey Nurse Shark include scuba diving and shark viewing operations.

Interactions between snorkel and scuba divers and Grey Nurse Sharks were once relatively common. However, these interactions are now rare (Pollard et al. 1996). Valerie Taylor noted that during the 1950s, schools of 30 to 50 Grey Nurse Sharks could be seen at almost every reef and island along the NSW coast, but during a week long trip to film the species in 1973, she only managed to find 11 sharks (Environment Australia 1997). In recent times, interactions between divers and packs of 30 to 50 Grey Nurse Sharks are relatively rare (Pollard et al 1996, Otway and Parker 2000).

The Grey Nurse Shark has become a big attraction to scuba divers and increasing pressure has been placed on operators to take divers to places where they can encounter these sharks (Otway and Parker 2000). It is possible that poorly managed shark viewing operations at popular sites may deter site-attached populations from residing in the area. There have been reports from Seal Rocks NSW (see Map 1) of scuba divers disturbing Grey Nurse Sharks, either accidentally or deliberately (Pollard et al 1996).

If divers continue to keep their distance whilst diving with these sharks, experience would suggest that it is unlikely that scuba diving per se will have any detrimental effects on the sharks survival (Otway and Parker 2000). Divers are often in the best situations to observe Grey Nurse Sharks and show genuine interest in surveys, education and conservation of the species. Regular viewing trips, when properly managed, offer a good opportunity for data collection on these and other sharks (Bruce 1995).

While ecotourism is not currently perceived as a major threat to the Grey Nurse Shark, growth in this industry is expected and preventative actions taken now may reduce any impacts in the future. These actions may include a range of options such as seasonal closures of these activities in marine protected areas, or the development and uptake of a code of conduct for commercial operators and dive clubs. A code of conduct is discussed in detail in Part 4.4.

Shark Deterrent Devices

Sharks show the greatest sensitivity to electrical stimuli in the animal kingdom. Further information is thus needed on the effect of shark deterrent devices on Grey Nurse Sharks. Devices such as the 'Shark Pod' (or Protective Oceanic Device) emit an electrical field that repels sharks. The Shark Pod repels sharks at close quarters by creating an electrical field around the scuba diver that totally disrupts the shark’s ampullae of Lorenzini. The ampullae of Lorenzini are the natural electrical detectors situated along a shark’s face that are used to detect minute electronic signals emitted by potential prey (Taylor 1997). It is not known what sort of effect these types of shark deterrent devices may have on Grey Nurse Sharks.

There is a report of a diver using a Shark Pod device in the shark gutter at the Tollgate Islands off Batemans Bay (N. Otway pers. comm.). The Grey Nurse Sharks were disturbed by the shark deterrent device and left the gutter that they normally inhabited. These Grey Nurse Sharks did not return until several days later. This type of impact needs to be prevented, and shark deterrent devices should not be used at known Grey Nurse Shark aggregation sites.

Management Responses

Future research is needed to determine whether the presence of scuba divers affects the behaviour of Grey Nurse Sharks. This information could be obtained through a research program using acoustic telemetry and smart tags to asses whether the behaviour of Grey Nurse Sharks is affected by: (1) varying numbers of scuba divers; and (2) the behaviour of the scuba divers whilst observing the sharks.

The Recovery Team recommends that there should be a moratorium on night diving on known Grey Nurse Shark aggregation sites. Grey Nurse Sharks are believed to be most active at night and it is possible that mating and reproduction occurs during this time, or early in the morning. The prevention of night time scuba diving at aggregation sites will reduce any impact on the species when it is most active. It is also recommended that shark deterrent devices are not used in known Grey Nurse Shark aggregation areas.

Issues

- Ecotourism activities relevant to Grey Nurse Sharks need to be managed effectively.

- A code of conduct for diving with Grey Nurse Sharks to be implemented by NSW Fisheries.

- Night diving on known aggregation sites should be prevented.

- Shark pod devices should not be used at known aggregation sites.

Prescribed Actions

E.1 - E.6 (see table 6)

3.6 Aquarium Trade

Grey Nurse Sharks are a good species for captive display due to their size, slow movement, relatively docile nature and slow metabolic rate. They are popular with the public due to their size and fierce appearance. As early as the 1950s and 1960s Grey Nurse Sharks that were retrieved alive would sometimes be sold to aquariums for display purposes (Fisheries Department of Western Australia 1996, Edwards 1997).

Currently there are 30 Grey Nurse Sharks in commercial aquaria in Australia (Table 3). These aquaria are also involved in Grey Nurse Shark captive breeding programs, survey work and educational programs. Six grey nurse pups have been born at Underwater World, Queensland. Aquariums have been actively involved in research activities on Grey Nurse Sharks including behavioural and breeding studies.

Table 3. Commercial aquaria holdings of Grey Nurse Sharks in Australia

Aquarium | Males | Females | Total |

Underwater World, Queensland | 3 | 4 | 7 |

Underwater World, WA | 1 | 7 | 8 |

Melbourne Aquarium, Victoria | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Sydney Aquarium, NSW | 2 | 3 | 5 |

Manly Oceanworld, NSW | 3 | 4 | 7 |

Total | 10 | 20 | 30 |

Management Responses

There is concern that with Grey Nurse Shark populations at such low numbers, it is unsustainable for the species to be taken from the wild for aquaria. In NSW there is a statewide moratorium on taking Grey Nurse Sharks from the wild for aquaria. This policy should be extended to all jurisdictions.

Grey Nurse Sharks already in captivity, and those bred for captive breeding programs, should be utilised as an educational resource. It is essential that Grey Nurse Sharks on public display be presented alongside educative programs informing the public on the biology, status and conservation problems of the species.

Issues

- Wild Grey Nurse Sharks should not be captured for exhibition in aquaria.

- Existing captive Grey Nurse Sharks should be utilised for their educative value.

Prescribed Actions

F.1 – F.3 (see table 6)

Part 4. Management Responses

4.1 Habitat Protection

Australian governments are committed to the establishment of a National Representative System of Marine Protected Areas (NRSMPA). Goals of the NRSMPA relevant to the protection of Grey Nurse Shark aggregation areas include: providing for the special needs of threatened species, migratory species, and species vulnerable to disturbance.

The Commonwealth through the Natural Heritage Trust funded NSW Fisheries to undertake the project Marine Protected Areas for Protection of Threatened Grey Nurse Sharks. A report for the project, entitled 'The biology, ecology, distribution, abundance and identification of Marine Protected Areas for the conservation of threatened Grey Nurse Sharks in South East Australian waters' (Otway & Parker 2000) has been published.

The Grey Nurse Shark is a migratory species that moves between particular sites along the east and west coasts of Australia. When not migrating Grey Nurse Sharks aggregate in or near deep sandy-bottomed gutters or in rocky caves around inshore rocky reefs and island at depths between 15 and 40 metres (Otway and Parker 2000). Known key aggregation sites for Grey Nurse Sharks in NSW are illustrated in Maps 3 and 4 and Table 4. Known key aggregation sites for Grey Nurse Shark in Queensland are illustrated in Map 2 and Table 4. Depending on the time of year, mature and juvenile Grey Nurse Sharks are found in concurrence with one another at these locations.

There is growing concern that legislative protection of Grey Nurse Sharks is not sufficient for their recovery and that strategies such as habitat protection are needed (Marsh 1995, Garbutt 1995). Habitat protection is of particular importance to Grey Nurse Sharks and particular areas where Grey Nurse Sharks aggregate, or particular habitats that are essential at different stages of their life history, should be provided with some effective form of protection (Otway and Parker 2000).

Recognising the importance of Grey Nurse Shark aggregation sites to the recovery of the species, it is essential that any potential threats to the species at aggregation sites must be mitigated against; the marine habitats at aggregation sites must not be directly or indirectly interfered with; and adequate supplies of food species must be made available, and be adequately protected and promoted, within the preferred foraging range of sharks dwelling at aggregation sites. This protection should include the establishment of effective marine protected areas (MPAs), such as ‘no take’ sanctuary zones, and seasonal or permanent closures of sites to both commercial and recreational fishers.

If MPAs were declared at the known aggregation sites for NSW waters (Table 4), a large percentage (approximately 72.4% averaged across the ten NSW Fisheries Grey Nurse Shark surveys) of the known Grey Nurse Shark population would receive a high degree of protection from threatening processes that occur at those locations (NSW Fisheries unpublished data).

Two sites, Pimpernel Rock in the Solitary Islands Marine Reserve and the Cod Grounds are in Commonwealth waters. These two sites account for 16.4% of the observed Grey Nurse Shark population (averaged across the ten NSW Fisheries Grey Nurse Shark surveys).

Under a new management plan for the Solitary Islands Marine Reserve, Pimpernel Rock is zoned as a Sanctuary Zone (IUCN category 1a) to provide high level protection for Grey Nurse Sharks and other sensitive marine species (Commonwealth of Australia 2001). The protection at Pimpernel Rock encompasses a 500-metre radius no take zone around the site that excludes all types of fishing. The other known Grey Nurse Shark aggregation sites in NSW and Qld should be considered for similar protection.

The Cod Grounds is a renowned Grey Nurse Shark site located approximately four nautical miles off the coast in Commonwealth waters near Laurieton on the NSW mid north coast. Large numbers of mature female and male Grey Nurse Sharks have been found at this site. During the NSW Fisheries Grey Nurse Shark survey, a minimum of 74 Grey Nurse Sharks were found at the site in September 2000. Sharks are observed at this site throughout the year but the numbers present between the period from May to October are greatest. Grey Nurse Sharks at the site are under pressure from both commercial and recreational fishers. There were reports in May 2001 by recreational scuba divers of recreational fishers catching and taking Grey Nurse Sharks from this site.

An example of habitat protection is at Fish Rock located at South West Rocks NSW. Scuba divers at this site noticed continued declines in the abundance of Grey Nurse Sharks in the area and voiced their concern at a public meeting. In July 1995 NSW Fisheries declared a drop line fisheries closure over an area covering a 500-metre radius around Fish Rock. This closure has now been extended until July 2003 (Otway and Parker 2000). Spearfishing is also restricted at Fish Rock with a restricted species list for spearfishing gazetted by NSW Fisheries on 31st July 1998. This list is predominantly of pelagic species (ie. tunas, marlins, mackerels, and kingfish) and species such as jewfish and morwong are now protected from spearfishing.

Since the selected fishing closures at Fish Rock, Grey Nurse Sharks are now found to aggregate from May to February. Prior to the fishing closures Grey Nurse Sharks were only found from May to November (N. Hitchins pers. comm.). Anecdotal evidence suggests that the numbers of Grey Nurse Shark and aggregation period has increased because their food sources (mainly jewfish) has been protected from fishing impacts (commercial drop lines and spearfishing). However, further protection is still required around Fish Rock as up to 75% of the Grey Nurse Shark population at the site have been found to exhibit line fishing related injuries (N. Hitchins pers. comm.), and there have been several reports of recreational fishers catching Grey Nurse Sharks.

4.1.1 Habitat Critical for the Survival of Grey Nurse Sharks

The EPBC Act specifies that recovery plans should identify the habitats that are critical to the survival of the species or community concerned and the actions needed to protect those habitats (S270 (2)(d)). It also requires that habitat critical to the survival of the species be entered on a register of critical habitat (S207A). In doing so, the EPBC Act provides a process for the identification and defining of habitats for threatened species. The register is given effect through Section 207A, and Regulation 7.09 provides advice on what areas should be included on the register and how an area should be defined. Section 207B requires that a person must not take an action that significantly damages critical habitat that is in Commonwealth areas.

Table 4 identifies an initial list of places within Australia considered to be habitat critical to the survival of Grey Nurse Sharks. This is an inclusive list and more sites can be added as they are identified over time. These sites were identified in the three year (1999-2001) NSW Fisheries study that determined the distribution and abundance of Grey Nurse Sharks in NSW. Approximately sixty sites were surveyed over the three year study where Grey Nurse Sharks had been known to occur. It was found that Grey Nurse Sharks were no longer found at many of these sites and that major aggregations were only found at the sites listed as habitat critical to the survival of Grey Nurse Sharks in table 4.

To date, there have been no distribution surveys in Western Australian waters for Grey Nurse Sharks. Therefore, no Grey Nurse Shark aggregation sites in Western Australia have been identified, and hence, no sites critical to the survival of Grey Nurse Sharks have been proposed for WA at this stage. The identification of sites in Western Australia will be difficult, as it is not known where the species occurs. It is recommended that a distribution survey, similar to the project run by NSW Fisheries, be initiated in Western Australia (action H.6. Table 6). Unlike New South Wales and Queensland, there are no known sites in Western Australia where divers can regularly observe Grey Nurse Sharks.

Over time, as other important places for Grey Nurse Sharks are identified they can be nominated to the register (action G.4. Table 6). The impacts on Grey Nurse Shark habitats will vary regionally depending on the level of pressure (such as fishing and ecotourism) placed on each site. The need for actions will be determined by these influences regionally or on a stock basis. The sites listed as habitat critical for the survival of Grey Nurse Sharks should also be considered for further protection such as marine protected areas, no take sanctuary zones or aquatic reserves (action G.5. Table 6).

Issues

- Further aggregation sites of Grey Nurse Sharks need to be identified.

- Sites identified as habitat critical for the survival of Grey Nurse Sharks to be listed on the EPBC Act register for critical habitat.

- Mechanisms are needed to protect identified aggregation sites.

Prescribed Actions

G.1 - G.5 (see table 6)

Table 4. Known habitat sites critical for the survival of Grey Nurse Sharks in Eastern Australia (from North to South).

Location | Site Name | Coordinates | Jurisdiction | Protection Status |

Rainbow Beach | Wolf Rock | 153º 12′ 10” E 25º 54′ 20” S | Queensland | None |

Moreton Island | China Wall | 153º 29′ 00” E 27º 05′ 10” S | Queensland | Habitat Zone1 – Moreton Bay Marine Park |

Moreton Island | Cherubs Cave | 153º 28′ 45” E 27º 07′ 35” S | Queensland | Habitat Zone1 – Moreton Bay Marine Park |

Moreton Island | Henderson’s Rock | 153º 28′ 45” E 27º 07′ 50” S | Queensland | Habitat Zone1 – Moreton Bay Marine Park |

Stradbroke Island | Flat Rock (Shark Alley) | 153º 33′ 00” E 27º 23′ 30” S | Queensland | Conservation Zone2 – Moreton Bay Marine Park |

Byron Bay | Julian Rocks - Cod Hole | 153º 37′ 45” E 28º 36′ 40” S | New South Wales | Aquatic Reserve3 |

Solitary Islands Marine Reserve | Pimpernel Rock | 153º 23′ 55” E 29º 41′ 55” S | Commonwealth | Sanctuary Zone (IUCN category 1a) – Solitary Islands Marine Reserve |

Solitary Islands | North Solitary Island (Anemone Bay) | 153º 23′ 25” E 29º 55′ 20” S | New South Wales | Habitat Protection Zone4– Solitary Islands Marine Reserve |

Solitary Islands | South Solitary Island (Manta Arch) | 153º 16′ 05” E 30º 12′ 10” S | New South Wales | Habitat Protection Zone4– Solitary Islands Marine Reserve |

South West Rocks | Green Island | 153º 05′ 30” E 30º 54′ 40” S | New South Wales | None |

South West Rocks | Fish Rock | 153º 06′ 05” E 30º 56′ 25” S | New South Wales | Restrictions on spearfishing / drop line fisheries closure |

Laurieton | Cod Grounds | 152º 54′ 30” E 31º 40′ 55” S | Commonwealth | None |

Forster | Pinnacle | 152º 36′ 00” E 32º 13′ 40” S | New South Wales | None |

Seal Rocks | Big Seal | 152º 33′ 15” E 32º 27′ 50” S | New South Wales | None |

Seal Rocks | Little Seal | 152º 32′ 55” E 32º 28′ 30” S | New South Wales | None |

Port Stephens | Little Broughton Island | 152º 20′ 00” E 32º 37′ 05” S | New South Wales | None |

Sydney | Maroubra - Magic Point | 151º 15′ 50” E 33º 57′ 20” S | New South Wales | None |

Bateman's Bay | Tollgate Islands | 150º 15′ 45” E 35º 44′ 50” S | New South Wales | None |

Narooma | Montague Island | 150º 13′ 40” E 36º 14′ 30” S | New South Wales | None |

Note: Coordinates were obtained from a variety of sources. These were subsequently checked against a number of data layers (eg Nautical Charts, AMBIS2001), and have been rounded to the nearest 5'' (approximately +/- 75m) to indicate their likely level of accuracy. Latitudes and longitudes have been determined by reference to GDA94. Habitat Zone1 – Moreton Bay Marine Park: These zones provide areas for reasonable use and enjoyment while maintaining productivity of the natural communities by excluding activities such as shipping operations and mining. Still allow all forms of recreational and commercial fishing. Conservation Zone2 – Moreton Bay Marine Park: This zone conserves the natural condition to the greatest possible extent, provide for recreational activities. Conservation zone allows all forms of recreational and commercial fishing but excludes trawling. Habitat Protection Zone4– Solitary Islands Marine Reserve: Refuges that protect important habitat but allow recreational and commercial fishing activities that have a ‘low impact’ on the environment. This zoning is under review (Marine Parks Authority 2001). |

4.2 Research Activities

The capacity of managers to make informed decisions about the best way to ensure the recovery of Grey Nurse Shark populations is hampered by a lack of knowledge. There are inadequate data available on Grey Nurse Shark biology, population numbers, abundance and distribution, and the effects human activities may have on their populations. There is a need to make decisions that will reduce the likelihood of further population declines.

Data sets that have been used to show a population decline of the Grey Nurse Shark include: beach meshing records for NSW and Queensland; reports from divers in NSW and a major survey of Grey Nurse Sharks carried out by NSW Fisheries and dive groups (refer to Community Involvement section – 4.4) (Otway and Parker 2000, Otway 2001). To date, ten statewide Grey Nurse Shark distribution and abundance surveys have been completed, covering approximately sixty sites. The numbers of Grey Nurse Sharks observed varied greatly along the entire NSW coast and the total number of animals observed in the ten consecutive surveys is shown in Table 5.

The surveys have documented the distribution and abundance of Grey Nurse Sharks along the east coast of NSW using standardised visual sampling techniques. Tagging studies of individuals at various locations along the coast, and subsequent sightings by divers, captures in beach protective shark nets, and inadvertent captures on setlines, would enable further information to be collected.

Tagging studies will enable:

- estimates of total population size, growth and mortality rates for the species,

- documentation of the inter-annual variability in abundances of Grey Nurse Sharks,

- identification of migratory patterns, localised (short-term) movements and possible home ranges, and hence the size of effective protected areas and alternative forms of protective management,

- an independent estimate of the rates of inadvertent capture as by-catch, and

- identification of localised movements.

There is very little information about the population status of Grey Nurse Sharks in Western Australia. The only information on Grey Nurse Sharks in WA is derived from commercial fisheries logbook data. There are no known aggregation sites in Western Australia and divers are not known to encounter Grey Nurse Sharks (R. McAuley pers. comm.). A research program is needed in Western Australia to determine the distribution and abundance of the species in these waters.

Grey Nurse Sharks are known to be migratory; the ‘nature’ of that migration along the east coast of Australia needs to be quantified, and any risks to the sharks during their migration reduced. Data from protective beachmeshing programs (Krogh 1994; Reid and Krogh 1992) and movements of tagged sharks from the records of gamefish anglers in NSW (Pepperell 1992) provide some evidence in support of migratory habits. However more information is required to test hypotheses concerning the movements of the Grey Nurse Shark in Australian waters (Otway and Parker 2000).

Table 5. Numbers of Grey Nurse Sharks observed during NSW Fisheries surveys, 1998-01

| Size | Total Males | Total Females | Total Unid. | Total | Ratio M:F | Sharks/site |

Survey 1 | | 34 | 75 | 27 | 136 | 1:2.2 | 2.2 |

Nov - Dec | < 2 m | 22 | 41 | 13 | | | |

1998 | 2 - 3 m | 11 | 33 | 14 | | | |

| > 3 m | 1 | 1 | 0 | | | |

Survey 2 | | 20 | 72 | 37 | 129 | 1:3.6 | 2.5 |

Mar | < 2 m | 6 | 28 | 17 | | | |

1999 | 2 - 3 m | 5 | 39 | 5 | | | |

| > 3 m | 9 | 3 | 0 | | | |

Survey 3 | | 81 | 79 | 44 | 207 | 1:0.9 | 4.1 |

May - Jun | < 2 m | 18 | 37 | 22 | | | |

1999 | 2 - 3 m | 56 | 37 | 21 | | | |

| > 3 m | 7 | 5 | 1 | | | |

Survey 4 | | 29 | 118 | 40 | 187 | 1:4.1 | 4.3 |

Aug - Sep | < 2 m | 14 | 52 | 18 | | | |

1999 | 2 - 3 m | 13 | 56 | 22 | | | |

| > 3 m | 2 | 10 | 0 | | | |

Survey 5 | | 35 | 62 | 35 | 132 | 1:1.8 | 2.3 |

Nov - Dec | < 2 m | 18 | 30 | 27 | | | |

1999 | 2 - 3 m | 13 | 27 | 7 | | | |

| > 3 m | 4 | 5 | 1 | | | |

Survey 6 | | 38 | 74 | 37 | 149 | 1:1.9 | 2.3 |

Mar - Apr | < 2 m | 11 | 23 | 15 | | | |

2000 | 2 - 3 m | 19 | 49 | 19 | | | |

| > 3 m | 8 | 2 | 3 | | | |

Survey 7 | | 113 | 126 | 53 | 292 | 1:1.1 | 4.7 |

May - Jun | < 2 m | 15 | 34 | 28 | | | |

2000 | 2 - 3 m | 82 | 71 | 21 | | | |

| > 3 m | 16 | 21 | 4 | | | |

Survey 8 | | 31 | 77 | 38 | 146 | 1:2.5 | 2.6 |

Aug - Sep | < 2 m | 6 | 15 | 17 | | | |

2000 | 2 - 3 m | 23 | 51 | 20 | | | |

| > 3 m | 2 | 11 | 1 | | | |

Survey 9 | | 25 | 63 | 32 | 120 | 1:2.5 | 1.9 |

Nov - Dec | < 2 m | 7 | 29 | 25 | | | |

2000 | 2 - 3 m | 18 | 32 | 7 | | | |

| > 3 m | 0 | 2 | 0 | | | |

Survey 10 | | 42 | 89 | 35 | 166 | 1:2.1 | 3.5 |

Mar - Apr | < 2 m | 13 | 44 | 21 | | | |

2001 | 2 - 3 m | 24 | 41 | 13 | | | |

| > 3 m | 5 | 4 | 1 | | | |

A fundamental property of any long term monitoring program is the collection of data that is consistent across the program, and ideally throughout the range of the species. Valuable information on population trends for Grey Nurse Sharks will, in all probability, take years of consistent monitoring effort. It will be necessary to ensure that spatial and temporal variation in abundance of Grey Nurse Sharks is documented on a regular basis (Otway and Parker 1999). NSW Fisheries currently maintains data from the Grey Nurse Sharks surveys carried out to date.

Autopsies of any dead Grey Nurse Sharks are important for collecting vital biological information about the species and will increase data sets needed for modelling the population. In NSW dead Grey Nurse Sharks are to be autopsied and in Queensland they are measured, sexed and their stomach contents examined. Commercial fishers are encouraged to pass on any inadvertently caught and killed Grey Nurse Shark carcasses to fisheries biologists to assist in the collection of biological data (eg size, sex, age, stomach contents). Collection and subsequent analysis of genetic material from these sharks will help researchers determine the genetic separation between the western and eastern Australian populations.

Environment Australia has provided funding to NSW Fisheries to monitor wobbegong sharks (Orectolobus maculatus and Orectolobus ornatus) at sites utilised by Grey Nurse Sharks. The scuba diving community will provide information on sightings of wobbegong sharks. The commercial catch of wobbegong sharks will also be analysed to provide an indication of the current level of harvest and potential interactions with Grey Nurse Sharks. This information will provide a preliminary understanding of the interaction between wobbegongs and Grey Nurse Shark.

Issues

- Monitoring for Grey Nurse Sharks is essential to establish spatial and temporal population trends and measure recovery.

- More biological and genetic data for Grey Nurse Sharks is needed.

- Population status of Western Australia needs to be determined.

- More information is needed on the impact of commercial wobbegong fishing on Grey Nurse Shark.

- Commercial fishers should be asked to provide Grey Nurse Shark carcasses to fisheries biologists.

Prescribed Actions

H.1 - H.8 (see table 6)

4.3 Population Modelling and Demography