A description of

Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park

Introduction

Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park is part of an extensive Aboriginal cultural landscape that stretches across the Australian continent. The park represents the work of Anangu and nature during thousands of years. Its landscape has been managed using traditional Anangu methods governed by Tjukurpa, Anangu Law.

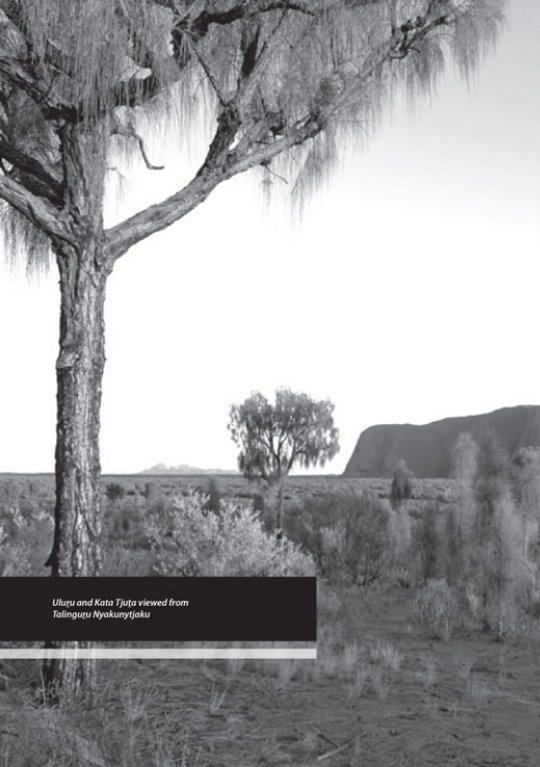

Within Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park is Uluru, arguably the most distinctive landscape symbol of Australia, nationally and internationally. It conveys a powerful sense of the very long time during which the landscape of the Australian continent has evolved. Far from the coastal cities, and with its rich red tones, for some it epitomises the isolation and starkness of Australia’s desert environment. When coupled with the profound spiritual importance of many parts of Uluru to Anangu (Western Desert Aboriginal people, see Map 1), these natural qualities have resulted in the use of Uluru in Australia and elsewhere as the symbolic embodiment of the Australian landscape. As a consequence, Uluru has become the focus of visitors’ attention in the Central Australian region, while other parks offer a complementary range of experiences.

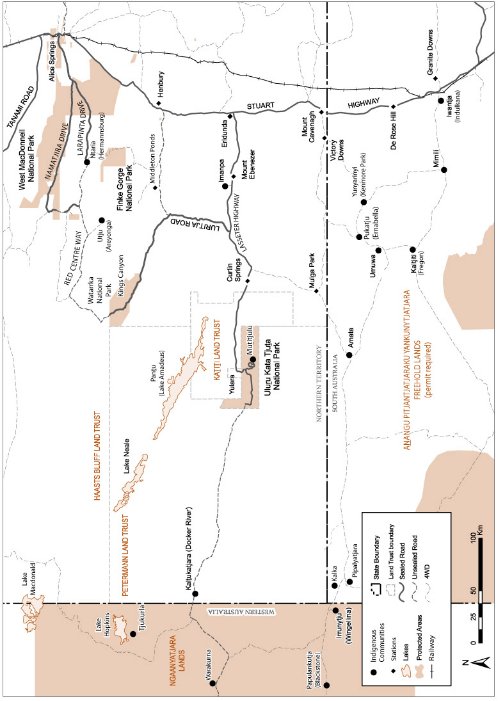

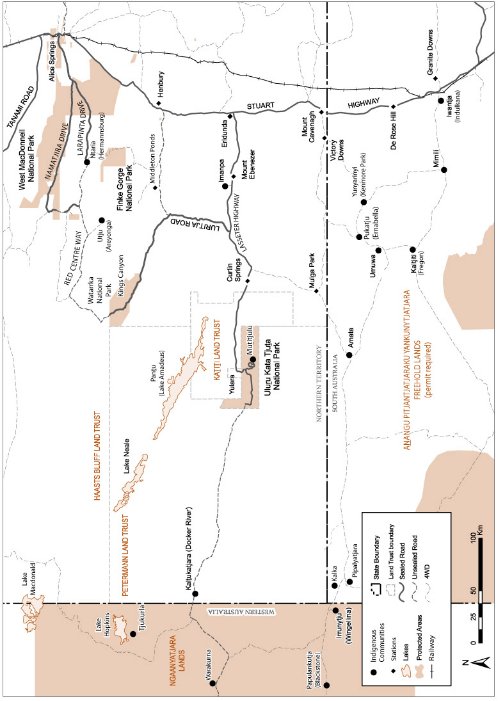

The park is owned by the Uluru–Kata Tjuta Aboriginal Land Trust. It covers about 1,325 square kilometres and is 335 kilometres by air and about 470 kilometres by road to the south-west of Alice Springs (see Map 2). The Ayers Rock Resort at Yulara adjoins the park’s northern boundary. Both the park and the resort are surrounded by Aboriginal freehold land held by the Petermann and Katiti Land Trusts (see Map 3).

The values of the park

Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park is a cultural landscape representing the combined works of Anangu and nature over millennia.

The importance of Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park’s cultural landscape is reinforced by the inscription of cultural and natural values for the park on the World Heritage List and also on the Australian Government’s Commonwealth and National Heritage Lists. The listed World Heritage values for the park are described in Appendix B to this plan, National Heritage values in Appendix C and Commonwealth Heritage values in Appendix D.

Cultural values

Anangu is the term that Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara Aboriginal people, from the Western Desert region of Australia, use to refer to themselves. Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara are the two principal dialects spoken in Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park.

Aboriginal people and their culture have always been associated with Uluru. According to Anangu, the landscape was created at the beginning of time by ancestral beings. Anangu are the direct descendants of these beings and they are responsible for the protection and appropriate management of these lands. The knowledge necessary to fulfil these responsibilities has been passed down from generation to generation through Tjukurpa, the Law.

Tjukurpa

Ananguku Tjukurpa kunpu pulka alatjitu ngaranyi. Inma pulka ngaranyi munu Tjukurpa pulka ngaranyi ka palula tjana-languru kulini munu uti nganana kunpu mulapa kanyinma. Miil-miilpa ngaranyi munu Ananguku Tjukurpa nyanga pulka mulapa. Tjukurpa panya tjamulu, kamilu, mamalu, ngunytjulu nganananya ungu, kurunpangka munu katangka kanyintjaku.

© Tony Tjamiwa

There is strong and powerful Aboriginal Law in this Place. There are important songs and stories that we hear from our elders, and we must protect and support this important Law. There are sacred things here, and this sacred Law is very important. It was given to us by our grandfathers and grandmothers, our fathers and mothers, to hold onto in our heads and in our hearts. ©

Tjukurpa unites Anangu with each other and with the landscape. It embodies the principles of religion, philosophy and human behaviour that are to be observed in order to live harmoniously with one another and with the natural landscape. Humans and every aspect of the landscape are inextricably one.

According to Tjukurpa, there was a time when ancestral beings, in the forms of humans, animals and plants, travelled widely across the land and performed remarkable feats of creation and destruction. The journeys of these beings are remembered and celebrated and the record of their activities exists today in the features of the land itself. For Anangu, this record provides an account, and the meaning, of the cosmos for the past and the present. When Anangu speak of the many natural features within Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park their interpretations and explanations are expressed in terms of the activities of particular Tjukurpa beings, rather than by reference to geological or other explanations. Primarily, Anangu have a spiritual interpretation of the park’s landscape. In traditional terms, therefore, they speak of the park’s spiritual meaning, not just of the shape its surface features take.

Tjukurpa prescribes the nature of the relationships between those responsible for the maintenance of Tjukurpa and the associated landscape, their obligations, and the obligations of those who visit that land. The central attributes of these relationships are integrity, respect, honesty, trust, sharing, learning, and working together as equals.

In all interactions with visitors to their land, Anangu stress the need for:

Tjurkulytju kulintjaku kuranyu nguru pinangku munu utira ngukunytja tjura titutjaraku witira kanyintjikitjaku kututungku kulira.

© Tony Tjamiwa

Clear listening, which starts with the ears, then moves to the mind, and ultimately settles in the heart as knowledge. ©

Tjukurpa is the foundation of Anangu life. It encompasses:

- Anangu religion, law and moral systems

- the past, the present and the future

- the creation period when ancestral beings, Tjukaritja/Waparitja, created the world as it is now

- the relationship between people, plants, animals and the physical features of the land

- the knowledge of how these relationships came to be, what they mean, and how they must be maintained in daily life and in ceremony.

Tjukurpa is also the foundation of joint management for the park. Anangu consider that, to care properly for the park, Tjukurpa must come first. Their description of what this means in practice is:

- passing on knowledge to young men and women

- learning to find water and bush food

- travelling around country

- learning about, collecting and using bush medicines

- visiting sacred sites

- visiting family in other communities

- watching country and making sure Tjukurpa is observed

- remembering the past

- thinking about the future

- keeping visitors safe – keeping women away from men’s sites and keeping men away from women’s sites

- teaching visitors how to observe and respect Tjukurpa

- teaching park staff and other Piranpa how to observe Tjukurpa

- bringing up children strong and caring for children

- growing country by doing the right things, for example, hunting at the right times of the year and not at wrong times or in the wrong way

- keeping Anangu men and women safe

- making country alive, for example, through stories, ceremony and song

- keeping the Mutitjulu Community private and safe

- putting the roads and park facilities in proper places so that sacred places are safeguarded

- cleaning and protecting rock waterholes inside and outside the park

- collecting bush foods and seeds

- old men teaching stories, young boys and men learning stories

- old women teaching stories, young girls and women learning stories

- looking after country, for example, traditional burning

- hunting food to feed young children and old people.

Cultural landscape

Nintiringkula kamila tjamula tjanalanguru. Wirurala nintiringu munula watarkurinytja wiya. Nintiringkula tjilpi munu pampa nguraritja tjutanguru, munula rawangku tjukurpa kututungka munu katangka kanyilku. Ngura nyangakula ninti – nganana ninti.

© Barbara Tjikatu

We learnt from our grandmothers and grandfathers and their generation. We learnt well and we have not forgotten. We’ve learnt from the old people of this place, and we’ll always keep the Tjukurpa in our hearts and minds. We know this place – we are ninti, knowledgeable. ©

As a cultural landscape representing the combined works of nature and Anangu and manifesting the interaction of humankind and its natural environment, the landscape of Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park is in large part the outcome of millennia of management using traditional Anangu methods governed by Tjukurpa.

Anangu’s knowledge of sustainable land use derives from a detailed body of ecological knowledge which includes a classification of ecological zones. This knowledge continues to contribute significantly to ecological research and management of the park. Anangu landscape management followed a traditional regime of fire management, and temporary water resources were husbanded by cleaning and protecting soaks and rockholes; Anangu landscape management methods are now integral to management of the park.

There are numerous specific sites of significance to Anangu in the park, and most of them are at or close to Uluru and Kata Tjuta. The significance of the sites is the way they are interconnected by the iwara (tracks) of the ancestral beings. Management of the landscape today is governed by Tjukurpa established by these beings. There are many hundreds of painting sites around the base of Uluru, generally associated with rock shelters. While there are fewer art sites at Kata Tjuta, there are stone arrangements and rock engravings. There are also numbers of known past habitation sites in the park. The park thus contains significant physical evidence of one of the oldest continuous cultures in the world.

Tjukurpa as a guide to management

Tjukurpa

Manta atunymananyi, kuka tjuta atunymananyi munu mai tjuta atunymananyi. Kaltja atunymananyi munu Tjukurpa kulu-kulu. Park atunymananyi. Kumuniti atunymananyi.

© Judy Trigger

Looking after land. Looking after animals, and bush tucker. Looking after culture and Tjukurpa. Looking after park. Looking after community. ©

The area of Tjukurpa that relates to ecological responsibility is what Anangu usually refer to as ‘looking after country’. Caring for the land is an essential part of ‘keeping the Law straight’. From this area of Tjukurpa Anangu learn their rights and responsibilities in relation to sites within country, other people who are related to the land in the same way, and the ancestral beings with whom sites and tracks are associated. This is also where Anangu learn about the formal responsibilities of caring for the land. Creations that derive from Tjukurpa are not confined to geological features such as rock faces, boulders and waterfalls. Plants and animals derive from the creative period of Tjukurpa. Much of what Piranpa would call biological or ecological knowledge about the behaviour and distribution of plants and animals is considered by Anangu to be knowledge of Tjukurpa.

Such knowledge commonly forms part of the content of the stories about the ancestral beings’ activities and is taught in association with exploitation of food resources. Thus, whilst travelling the land to gather and hunt for food, Anangu learn how such activities are related to a unified scheme of life that stretches from the beginning of all things to the present. Tjukurpa also refers to the record of all activities of ancestral beings, from the beginning to the end of their travels.

With few exceptions, Tjukurpa within the park is part of much wider travels of ancestral beings. The relationship of the park area with other areas is traceable by sites along the tracks of ancestral beings on their way to or from Uluru or Kata Tjuta, thus making the park an important focus of many converging ancestral tracks.

Around Uluru, for instance, there are many examples of ancestral sites. The Mala Tjukurpa tells of mala (the rufous hare-wallaby, Lagorchestes hirsutus) that travelled to Uluru from the north. Subsequently mala fled to the south and south-east (into South Australia) as they attempted to escape from Kurpany, an evil dog-like creature that had been specifically created and sent from Kikingkura (close to the Western Australian border). It is important that planning in the park take into account the Anangu perception that, through these links, areas in the park derive their meaning from, and contribute meaning to, places outside the park. Links with other places form an integral part of the way in which Anangu ‘map’ the park’s landscape, which in turn has implications for their decisions about areas in the park and the strong relationships they wish to maintain with the entire Western Desert area.

The location of homelands in Anangu lands bordering the park has been heavily influenced by such landscape ‘mapping’. The homelands also reinforce the social connections and ritual obligations among Nguraritja. Taken together, they mean a responsibility for looking after country. Thus the homelands are integral to the Tjukurpa of Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park.

Anangu have used landscape ‘maps’ for many management purposes during the operation of previous plans. This knowledge has assisted with the location of park developments, identifying animal and plant colonies, and interpreting landscape features for visitors to the park. The Liru and Mala Walks, in particular, were constructed on the basis of landscape ‘maps’ derived from Tjukurpa.

Tjukurpa

Anangu have lived in and maintained the landscape and Tjukurpa at Uluru and Kata Tjuta for many thousands of years. The story of this occupation and land use can be reconstructed from archaeological deposits, from the rock art and engravings Anangu created to depict events from Tjukurpa and their own lives, and from the personal histories of people living in the park today. Anangu history is an important part of the park’s cultural significance and is worthy of record and preservation. Preservation of rock art is a core aspect of park management and the park has an ongoing oral history program.

Tjukurpa

Iriti Anangu walytja-piti tjuta ninti nyinangi, panya yaaltji-yaaltji wirura tjukaruru nyinanytjaku. Yangupala tjutanya tjilpingku munu pampangku nintipungkupai ka mamangku munu ngunytjungku wirura maingka tjitji kanyilpai. Kuwari nganana park atunymananyi munula nyanga alatji ngarantjaku mukuringanyi.

© Pulya Taylor

In the old way families knew how to behave and live well. The young were taught by the old and the parents provided for them all. Now we have the park to look after and we want it to work in this way. ©

Like any body of law, Tjukurpa is the source of rules of appropriate behaviour that relate people to other people and people to the land. The first area of appropriate behaviour deals with day-to-day things such as protocol, the relationship between men and women, marriage, child rearing, and the relationships between the old and the young and between various other categories of kin. From earliest times, throughout the entire Western Desert area, Anangu have been able to establish through kinship or family ties their social relationships with other people so as to be able to use kin terms comfortably. They then deal with each other as family (walytja), even if they have never before met. This is how Anangu are able to refer to themselves as ‘one people’. These structured relationships carry intricate economic, social and religious rights and responsibilities. One of the advantages of such social organisation is that it supports cooperative strategies for movement over the land and for exploitation of the land’s resources, even by people who cannot be constantly in contact with one another.

Employment arrangements for Anangu working in the park take into account social and religious obligations by allowing for considerable flexibility in work hours. Where Anangu have been required to go away for several weeks at a time for religious ceremonies or to honour other social or family responsibilities, Parks Australia has been able to adapt work requirements so as not to disadvantage Anangu and not to affect overall park management responsibilities. The park was closed for three hours in 1987 to allow the unobserved transit through the park of Anangu who were engaged in ceremonial activity. Since this time parts of the park have sometimes been closed for ceremonial reasons. These closures are effected in a way that minimises disruption to visitors.

Park staff receive instruction in aspects of social behaviour that affect Anangu work practices. This includes avoidance relationships (kin not permitted to talk to or look at each other), the appropriate type of work for men and women, and the precedence of old people over the young in decision-making. These aspects of social behaviour are taken into account in the development of work programs.

Tjukurpa:

Wangkanytjaku iwara patu-patu wirura tjunkunytjaku minga tjutaku munu alatjinku ngura Tjukuritja tjuta wirura anga kanyintjaku munu minga tjuta safe kanyintjaku.

© Millie Okai

Talk about the proper place to put the roads for visitors and safeguard sacred areas and keep visitors safe. ©

For Anangu, an essential part of ‘keeping the Law straight’ involves ensuring that knowledge is not imparted to the wrong people and that access to significant or sacred sites is not gained by the wrong people, whether ‘wrong’ means men or women, Piranpa visitors, or certain other Anangu.

It is as much a part of Anangu religious responsibility to care for this information properly as it is for other religions to care for their sacred precincts and relics. The same holds true for sites and locations on ancestral tracks where events that are not for public knowledge took place. Neither knowledge of nor access to such sites is permissible under Anangu Law. Even inadvertent access to some sites constitutes sacrilege. Special management measures have been taken to help Anangu continue protecting Tjukurpa whilst allowing visitors to enjoy

the park. One of the main objectives of the park’s interpretive strategy is to enhance visitors’ knowledge and appreciation of what constitutes culturally appropriate behaviour as part of the experience of visiting a jointly managed national park.

Policies and regulations in relation to visitor management have been developed in such a way as to emphasise Anangu perceptions of appropriate visitor behaviour. Of particular importance are policies and guidelines developed by the Board of Management for commercial filming and photography and the fencing off of certain areas around the base of Uluru, to ensure visitors do not inadvertently contravene Tjukurpa restrictions.

The Uluru–Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre has greatly increased opportunities for visitors to learn

about Tjukurpa, Anangu culture and the park. Within the bounds of appropriate access, Tjukurpa provides a basis for most of the interpretation of the park to visitors. Anangu want visitors to understand how they interpret this landscape. Tjukurpa contains information about the landscape features, the ecology, the plants and animals, and appropriate use of areas of the park. Tjukurpa has been passed down through the generations and can be shared with visitors. In addition, Anangu believe that visitors’ understanding of the park can be enhanced by providing information about how Anangu use the park’s resources and the history of their use of these resources.

Map 1 – Approximate present day extent of Western Desert language speakers

Map 2 – Location of Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park and distances by air from major cities

Map 3 – Aboriginal communities and their proximity to the park

Natural values

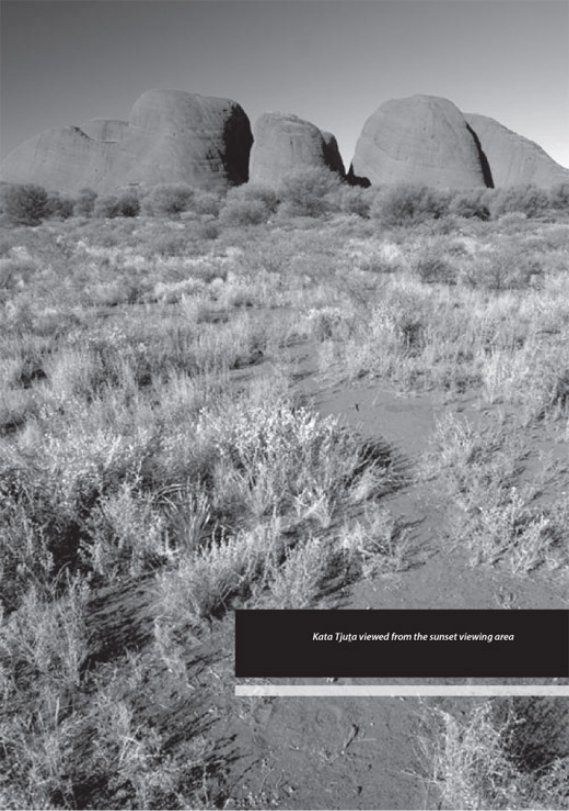

The park’s landscape is dominated by the iconic massifs of Uluru and Kata Tjuta. Uluru is made from sedimentary rock called arkose sandstone. It is 9.4 kilometres in circumference and rises about 340 metres above the surrounding plain. Kata Tjuta comprises 36 rock domes of varying sizes made from a sedimentary rock called conglomerate. One of the domes, rising about 500 metres above the plain (or 1,066 metres above sea level), is the highest feature in the park. These two geological features are striking examples of geological processes and erosion occurring over time and of the age of the Australian continent. The contrast of these monoliths with the surrounding sandplains creates a landscape of exceptional natural beauty of symbolic importance to both Anangu and non-Aboriginal cultures. The Uluru and Kata Tjuta massifs, rocky slopes and foothills contribute to the park’s high biodiversity. The many other patterns and structures in the landscape reflect the region’s evolutionary history and give important clues about limitations on resource use and management (Gillen et al. 2000).

The Uluru–Kata Tjuta landscape is a representative cross-section of the Central Australian arid ecosystems. The main ecological zones in the park are:

- puli – rock faces and vegetated hill slopes

- puti – woodlands, particularly the mulga flats between sandhills

- tali and pila – sand dunes and sandplains

- karu – creek beds.

The park has a particularly rich and diverse suite of arid environment species, most of which are unique to Australia. The park supports populations of a number of relict and endemic species associated with the unique landforms and habitats of the monoliths. Uluru and Kata Tjuta provide runoff water which finds its way into moist gorges and drainage lines where isolated populations persist in an environment otherwise characterised by infertile and dry dunefields. In addition, an exceptionally high species diversity is associated with the transitional sandplain that lies between the mulga outwash zone around the monoliths and the dunefields beyond.

Across the park’s ecological zones 619 plant species have been recorded, among them seven rare or endangered species, which are generally restricted to the moist areas at the bases of Uluru and the domes of Kata Tjuta. These include five relict species – Stylidium inaequipealum, Parietaria debilis, Ophioglossum lusitanicum subsp. coriaceum, Isoetes muelleri and Triglochin calcitrapum. In addition, the main occurrence of the sandhill wattle Acacia ammobia is just east of Uluru. The park’s flora represents a large portion of plants found in Central Australia.

A total of 26 native mammal species, including several species of small marsupials and native rodents and bats, have been recorded in the park. These include the recently reintroduced mala. Reptile species are found in numbers unparalleled anywhere in the world and are well adapted to the arid environment; 74 species have been recorded to date, including a newly described species in 2006. As well, 176 native bird species, four amphibian species and many invertebrate species have been recorded. An unusually diverse fauna assemblage occurs in an area extending north from Uluru to the west of Yulara town site and west to the Sedimentaries.

The legless-lizard Delma pax is represented by an apparently relict population at Uluru. The great desert skink (Egernia kintorei) is known from the transitional sandplain in the park. The scorpion Cercophonius squama, a temperate species, occurs at Mutitjulu on the southern margin of Uluru. Several relict plants are confined to moist gorges at Uluru and Kata Tjuta: Stylidium inaequipetalum, Parietaria debilis, Ophioglossum lusitanicum coriaceum, Isoetes muelleri, and Triglochin calcitrapum. The grass Eriachne scleranthoides is confined to Kata Tjuta and one other location.

There are significant populations of the southern marsupial mole (Notoryctes typhlops), the striated grasswren (Amytornis striatus), the rufous-crowned emu-wren (Stipiturus ruficeps), the scarlet-chested parrot (Neophema splendida), the grey honeyeater (Conopophila whitei), the desert mouse (Pseudomys desertor), and a skink Ctenotus septenarius.

Bioregional significance

Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park is located in the Greater Sandy Desert bioregion which includes parts of the Northern Territory and Western Australia. This bioregion has less than five per cent of its total area within protected areas – the park is one of only five reserves and plays a significant role in contributing to long-term biodiversity conservation in the region. Within the bioregion, the park is representative of a broad landform structure that is a recurring pattern in arid Central Australia (Gillen et al. 2000).

History of the park

During the 1870s expedition parties headed by explorers Ernest Giles and William Gosse were the first Europeans to visit the area. As part of the colonisation process, Uluru was named ‘Ayers Rock’ and Kata Tjuta ‘The Olgas’ by these explorers in honour of political figures of the day. Further explorations quickly followed with the aim of establishing the area’s potential for pastoral expansion. It was soon concluded that the area was unsuitable for pastoralism. Few Europeans visited over the following decades, apart from small numbers of mineral prospectors, surveyors and scientists.

In the 1920s the Commonwealth, South Australian and Western Australian Governments declared the great central reserves, including the area that is now the park, as sanctuaries for a nomadic people who had virtually no contact with white people. Despite this initiative, small parties of prospectors continued to visit the area and from 1936 were joined by the first tourists. A number of the oldest people now living at Uluru can recall meetings and incidents associated with white visitors during this period. Some of that contact was violent and engendered a fear of white authority. From the 1940s the two main reasons for permanent and substantial European settlement in the region were Aboriginal welfare policy and the promotion of tourism at Uluru. These two endeavours, sometimes in harmony and sometimes in conflict, have determined the relationships between Europeans and Anangu.

In 1948 the first vehicular track to Uluru was constructed, responding to increasing tourism interest in the region. Tour bus services began in the early 1950s and later an airstrip, several motels and a camping ground were built at the base of Uluru. In 1958, in response to pressures to support tourism enterprises, the area that is now the park was excised from the Petermann Aboriginal Reserve to be managed by the Northern Territory Reserves Board as the Ayers Rock–Mount Olga National Park. The first ranger was the legendary Central Australian figure Bill Harney.

Post-war assimilation policies assumed that Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara people had begun a rapid and irreversible transition into mainstream Australian society and would give up their nomadic lifestyle, moving to specific Aboriginal settlements developed by welfare authorities for this purpose. Further, with increasing tourism development in the area from the late 1950s, Anangu were discouraged from visiting the park. However, Anangu continued to travel widely over their homelands, pursuing ceremonial life, visiting kin, and hunting and collecting food. The semi-permanent water available at Uluru made it a particularly important stopping point on the western route of these journeys.

By the early 1970s Anangu found their traditional country unprecedentedly accessible with roads, motor cars, radio communications and an extended network of settlements. At a time of major change in government policies, new approaches to welfare policies promoting economic self-sufficiency for Aboriginal people began to conflict with the then prevailing park management policies. The Ininti Store was established in 1972 as an Aboriginal enterprise on a lease within the park offering supplies and services to tourists; this became the nucleus of a permanent Anangu community within the park.

The ad hoc development of tourism infrastructure adjacent to the base of Uluru that began in the 1950s soon produced adverse environmental impacts. It was decided in the early 1970s to remove all accommodation related tourist facilities and re-establish them outside the park. In 1975 a reservation of 104 square kilometres of land beyond the park’s northern boundary, 15 kilometres from Uluru, was approved for the development of a tourist facility and an associated airport, to be known as Yulara. The campground within the park was closed in 1983 and the motels finally closed in late 1984, coinciding with the opening of the Yulara resort.

Confusion about representation of Anangu in decision-making associated with the relocation of facilities to Yulara led to decisions being made which were adverse to Anangu interests. It was not until passage of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Land Rights Act) and the subsequent establishment of the Central Land Council that Anangu began to influence the ways in which their views were represented to government.

Establishment of the park

On 24 May 1977 the park became the first area declared under the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1975 (NPWC Act), under the name Uluru (Ayers Rock–Mount Olga) National Park. The NPWC Act was replaced by the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) in 2000; the declaration of the park continues under the EPBC Act. The park was declared over an area of 132,550 hectares and included the subsoil to a depth of 1,000 metres. The declaration was amended on 21 October 1985 to include an additional area of 16 hectares. The Territory Parks and Wildlife Commission (the successor to the Northern Territory Reserves Board) continued with day-to-day management. During this period Anangu indicated their interest in the park and its management, including requesting protective fencing of sacred sites and permission for houses to be built for older people to camp at Uluru to teach young people.

In February 1979 a claim was lodged under the Land Rights Act by the Central Land Council (on behalf of the traditional owners) for an area of land that included the park. The Aboriginal Land Commissioner, Mr Justice Toohey, found there were traditional owners for the park but that the park could not be claimed as it had ceased to be unalienated Crown land upon its proclamation in 1977. The claimed land to the north-east of the park is now Aboriginal land held by the Katiti Aboriginal Land Trust.

At a major ceremony at the park on 26 October 1985, the Governor-General formally granted title to the park to the Uluru–Kata Tjuta Aboriginal Land Trust. The inaugural Board of Management was gazetted on 10 December 1985 and held its first meeting on 22 April 1986. In 1993, at the request of Anangu and the Board of Management, the park’s official name was changed to its present name, Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park.

Because of continuing opposition from the then Northern Territory Government to the new management arrangements for the park, the situation whereby the Conservation Commission of the Northern Territory carried out day-to-day management on behalf of the Director became untenable. During 1986 the arrangements that had been in place since 1977 were terminated, and staff of the Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service, now Parks Australia within the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, have carried out day-to-day management since that time.

Joint management

Joint management is the term used to describe the working partnership between Nguraritja and relevant Aboriginal people and the Director of National Parks as lessee of the park. Joint management is based on Aboriginal title to the land, which is supported by a legal framework laid out in the EPBC Act.

National and international significance

How Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park is significant internationally

Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park is inscribed on the World Heritage List under the World Heritage Convention for its outstanding natural and cultural values. The first listing was declared for the park’s natural values in 1987 and the second listing was declared in 1994 for the park’s cultural values. Uluru is one of the few sites that are listed under the World Heritage Convention for both cultural and natural values. At the time of preparing this plan, the park is one of only 25 World Heritage sites listed for both its natural and cultural heritage. Appendix B to this plan summarises the park’s listing against the World Heritage criteria.

The independent International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), which assessed the cultural values of Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park for the World Heritage Council, gave international recognition of:

- Tjukurpa as a religious philosophy linking Anangu to their environment

- Anangu culture as an integral part of the landscape

- Anangu understanding of and interaction with the landscape.

In 1995 the Director and the Uluru–Kata Tjuta Board of Management were awarded the Picasso Gold Medal, the highest award given by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), for outstanding efforts to preserve the landscape and Anangu culture and for setting new international standards for World Heritage management.

The park is representative of one of the most significant arid land ecosystems in the world. As a Biosphere Reserve under the UNESCO Man and the Biosphere Programme, it joins 13 other biosphere reserves in Australia and an international network aiming to preserve the world’s major ecosystem types.

Numerous migratory species that occur in Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park are protected under international agreements such as the Bonn Convention for conserving migratory species, and Australia’s migratory bird protection agreements with China (CAMBA), Japan (JAMBA) and Korea (ROKAMBA). Appendix G to this plan lists the migratory species that occur in the park.

How Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park is significant nationally

Heritage status

The park is listed on the National Heritage List for its Indigenous cultural heritage and for its natural heritage. At the time of preparation of this plan, the National Heritage List values are the same as the World Heritage values.

Conservation

The national park status and effective conservation management of Uluru–Kata Tjuta contribute significantly towards meeting the objectives of a number of Australian national conservation strategies. These include the following:

- National Reserve System

The National Reserve System represents the collective efforts of the states, territories, the Australian Government, non-government organisations and Indigenous landholders to achieve an Australian system of terrestrial protected areas as a major contribution to the conservation of Australia’s native biodiversity. Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park makes a significant contribution to the National Reserve System, which aims to contain samples of all regional ecosystems across Australia, their constituent biota and associated conservation values, in accordance with the Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia.

The park is located in the Great Sandy Desert bioregion and is one of five protected areas in the bioregion, which together comprise less than 5 per cent of the bioregion’s total area. The sub-region (GSD2) in which the park is located has only 5.2 per cent of its total area in protected areas. - National Strategy for the Conservation of Australia’s Biological Diversity and the National Strategy for Ecologically Sustainable Development

Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park contributes to these strategies’ objectives of having a comprehensive, adequate and representative system of protected areas. The park contributes to the objectives of the National Strategy for the Conservation of Australia’s Biological Diversity by conserving biological diversity in situ, integrating biological diversity conservation and natural resource management, managing threatening processes, improving knowledge of biological diversity and involving the community in biodiversity conservation.

Economic considerations

Tourism is a major export industry in Australia and is actively promoted by governments at all levels. Along with other places of natural beauty in Australia such as Kakadu National Park and the Great Barrier Reef, Uluru has become a major tourism attraction for overseas visitors.

Joint management

Nguraritja mayatja tjutangku munu park mayatja tjutangku tjungungku wangkara rule tjuta palyanu munu tjakultjunanyi yaaltji-yaaltji Piranpa ranger tjuta wirura tjungu Anangu-wanu munu kumuniti-wanu warkaringkunytjaku.

© Topsy Tjulyata

Nguraritja and park leaders talked together and made rules and they explain how the non-Anangu rangers can work well in cooperation with Anangu and through the Community. ©

The park was one of the first jointly managed parks in Australia. Protected area and land management authorities and groups of Indigenous people interested in joint management from within Australia and overseas regularly visit the park to better understand how joint management arrangements operate.

How Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park is significant regionally

Cultural considerations

Park-angka unngu munu park-angka urilta Tjukurpa palunyatu ngaranyi kutjupa wiya. Ngura miil-miilpa tjuta park –angka ngaranyi – uwankara kutju ngaranyi, Tjukurpangka.

© Tony Tjamiwa

It is one Tjukurpa inside the park and outside the park, not different. There are many sacred places in the park that are part of the whole cultural landscape–one line. Everything is one Tjukurpa. ©

It is an expressed view of Nguraritja that this management plan should acknowledge the links, through Tjukurpa, between the park and adjoining lands in the region. These links have direct implications for the practice and maintenance of Tjukurpa associated with the park.

Conservation

Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park includes habitats not well represented in other protected areas in Central Australia. Other parks in the Central Australian region generally cover hill, mountain range or riverine country and are managed under relevant Northern Territory and state legislation.

The park is listed on the Commonwealth Heritage List for its Indigenous cultural heritage and for its natural heritage.

Several species in the park have conservation status in the Northern Territory – there are six Northern Territory listed vulnerable animal species, one endangered mammal species and two endangered plant species.

Economic considerations

The Central Australian community supports a number of tour operators and others who derive a significant proportion of their income from visitors to the park. Tourism is central to the regional economy, particularly in terms of employment, and it is important that tourism development in the park is compatible with other plans for regional development. The standard of visitor facilities that Parks Australia develops and maintains in the park greatly influences the quality of tourists’ experience of the region.

‘Looking After Uluru’ © Malya Teamay: The painting depicts the main features of the management plan, clockwise from top left: the Tjukurpa of Uluru; a map of the park showing Uluru and Kata Tjuta–inside the park’s boundary sits the Board of Management with Anangu and Piranpa Board Members working together to look after the park; the interpretation of the park’s values, and education about the park; administration and law enforcement; natural and cultural resource management; the Mutitjulu Community; and park infrastructure including bores, roads and telecommunications; the different coloured background shows that Tjukurpa is everywhere, both inside and outside the park.

Management Plan for

Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park

Part 1 – Introduction

1. Background

Part 1 of the plan sets out the context in which this 5th Plan was prepared. It describes previous plans and the network of legislative requirements, lease agreements and international agreements which underpin the content of the plan.

1.1 Previous management plans

This is the 5th Management Plan for Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park. The 4th Plan came into operation on 13 September 2000 and ceased to have effect on 28 June 2007.

1.2 Structure of this management plan

The structure of this plan reflects the Parks Australia Strategic Planning and Performance Assessment Framework, a set of priorities based on Australian Government policy and legislative requirements for the protected area estate that is the responsibility of the Director of National Parks.

The outcomes in the plan are developed against the following Key Result Areas (KRAs) reflected in the Strategic Planning and Performance Assessment Framework:

KRA 1: Natural heritage management (see Section 5 of the plan)

KRA 2: Cultural heritage management (see Section 5)

KRA 3: Joint management (see Section 4)

KRA 4: Visitor management and park use (see Section 6)

KRA 5: Stakeholders and partnerships (see Section 7)

KRA 6: Business management (see Section 8).

Appendix E details outcomes for the KRAs, which are also used to structure the State of the Parks report in the Director of National Parks’ Annual Report to the Australian Parliament.

1.3 Planning process

Section 366 of the EPBC Act requires that the Director of National Parks and the Board of Management (if any) for a Commonwealth reserve prepare management plans for the reserve. In addition to seeking comments from members of the public, the relevant land council and the relevant state or territory government, the Director and the Board are required to take into account the interests of the traditional owners of land in the reserve and of any other Indigenous persons interested in the reserve.

The Uluru–Kata Tjuta Board of Management resolved that consultations be undertaken with Anangu to seek comments on issues related to the management of the park. These meetings covered a range of park management issues including decision-making procedures; natural and cultural resource management; visitor management and park use and Anangu employment. A number of Board meetings were also conducted to enable the Board to consider the draft management plan and submissions received from members of the public.

Other stakeholder groups and individuals that were consulted during the preparation of this management plan include:

- tourism industry representatives, scientists, photography interest groups, representatives from Australian Government and Northern Territory Government agencies, and local community organisations

- the Central Land Council

- Parks Australia staff.

2. Introductory provisions

2.1 Short title

This management plan may be cited as the Uluru–Kata Tjuta Management Plan or the Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park Management Plan.

2.2 Commencement and termination

This management plan will come into operation following approval by the Minister under s.370 of the EPBC Act, on a date specified by the Minister or the date it is registered under the Legislative Instruments Act 2003, and will cease to have effect 10 years after commencement, unless revoked sooner or replaced with a new plan.

2.3 Interpretation (including acronyms)

In this management plan:

Aboriginal means a person who is a member of the Aboriginal race of Australia

Aboriginal land means

(a) land held by an Aboriginal Land Trust for an estate in fee simple under the Land Rights Act; or

(b) land that is the subject of a deed of grant held in escrow by an Aboriginal Land Council under the Land Rights Act.

Aboriginal tradition means the body of traditions, observances, customs and beliefs of Aboriginals generally or of a particular group of Aboriginals and includes those traditions, observances, customs and beliefs as applied in relation to particular persons, sites, areas of Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park, things and relationships

Anangu means an Aboriginal person or people generally (and more specifically those Aboriginal people with traditional affiliations with this region)

Australian Government means the Government of the Commonwealth of Australia

BFC means the Bushfires Council established by the Bushfires Act (NT)

Board of Management or Board means the Board of Management for Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park established under the NPWC Act and continued under the EPBC Act by the Environmental Reform (Consequential Provisions) Act 1999

CAMBA means the Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of the People’s Republic of China for the Protection of Migratory Birds and their Environment, informally known as the China–Australia Migratory Bird Agreement

CLC or Land Council means the Central Land Council established under the Land Rights Act

Commonwealth reserve means a reserve established under Division 4 of Part 15 of the EPBC Act

Community means the Mutitjulu Community

CSMS means the Cultural Site Management System

Director means the Director of National Parks under s.514A of the EPBC Act, and includes Parks Australia and any person to whom the Director has delegated powers and functions under the EPBC Act in relation to Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park

Domestic animal means an animal that is non-native to the local region, including a dog which is part dingo (Canis lupus dingo), which is owned by and/or has a dependent relationship with a person or persons

EPBC Act means the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, including Regulations under the Act, and includes reference to any Act amending, repealing or replacing the EPBC Act

EPBC Regulations means the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Regulations 2000 and includes reference to any Regulations amending, repealing or replacing the EPBC Regulations

Feral animal means a member of a domesticated species that has escaped the ownership, management and control of people and is living and reproducing in the wild

Gazette means the Commonwealth of Australia Gazette

GIS means geographic information system

ICIP means Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property

ICOMOS means the International Council on Monuments and Sites

Introduced species or animal means a species that is non-native to the local region which has been introduced to the park either by human or natural means. For the purposes of this plan, species that were once native to the region and have been reintroduced are excluded

IUCN means the International Union for Conservation of Nature

JAMBA means the Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of Japan for the Protection of Migratory Birds in Danger of Extinction and their Environment, informally known as the Japan–Australia Migratory Bird Agreement

Land Rights Act means the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976

Land Trust means the Uluru–Kata Tjuta Aboriginal Land Trust established under the Land Rights Act

Lease or Park Lease means the lease agreement between the Uluru–Kata Tjuta Aboriginal Land Trust and the Director in respect of the park, shown as Attachment A to this plan

Management plan or plan means this management plan for the park, unless otherwise stated

Management principles means the Australian IUCN reserve management principles set out in Schedule 8 of the EPBC Regulations (see Section 3 and Appendix H of this plan)

MCAC means the Mutitjulu Community Aboriginal Corporation

Minister means the Minister administering the EPBC Act

Nguraritja means the traditional Aboriginal owners of the park

NPWC Act means the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1975 and the Regulations under that Act

NT means the Northern Territory of Australia

NTFRS means the Northern Territory Fire and Rescue Service

OHS means occupational health and safety

Park means Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park

Parks Australia means the Director of National Parks and the agency that assists the Director in performing the Director’s functions under the EPBC Act. At the time of preparing the plan, the agency assisting the Director is the Parks Australia Division of the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts

Pest means any animal, plant or organism having, or with the potential to have, an adverse economic, environmental or social impact

Piranpa means non-Aboriginal people (literally white)

Ramsar Convention means the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat

Relevant Aboriginals means the traditional Aboriginal owners of the park, Aboriginal people entitled to use or occupy the park and Aboriginal people permitted by the traditional Aboriginal owners (Nguraritja) to reside in the park

Relevant Aboriginal Association means the Mutitjulu Community Aboriginal Corporation or any other incorporated Aboriginal association or group whose members live in or are relevant Aboriginals in relation to the park which is the successor to the Mutitjulu Community Aboriginal Corporation and which is approved as such in writing by the Central Land Council

ROKAMBA means the Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of the Republic of Korea on the Protection Of Migratory Birds, informally known as the Republic of Korea–Australia Migratory Bird Agreement

Traditional owners means the traditional Aboriginal owners as defined in the Land Rights Act (see also Nguraritja)

Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park means the area declared as a national park by that name under the NPWC Act and continued under the EPBC Act by the Environmental Reform (Consequential Provisions) Act 1999

UHF means ultra-high frequency

UNESCO means the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation

World Heritage Convention means the Convention for the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage

2.4 Legislative context

Land Rights Act and the Park Lease

All of the park is Aboriginal land under the Land Rights Act with title held by the Uluru–Kata Tjuta Aboriginal Land Trust. The Land Trust has leased its land to the Director in accordance with the Land Rights Act for the purpose of being managed as a Commonwealth reserve.

EPBC Act

The objects of the EPBC Act as set out in Part 1 of the Act are:

(a) to provide for the protection of the environment, especially those aspects of the environment that are matters of national environmental significance; and

(b) to promote ecologically sustainable development through the conservation and ecologically sustainable use of natural resources; and

(c) to promote the conservation of biodiversity; and

(ca) to provide for the protection and conservation of heritage; and

(d) to promote a co-operative approach to the protection and management of the environment involving governments, the community, land-holders and Indigenous peoples; and

(e) to assist in the co-operative implementation of Australia’s international environmental responsibilities; and

(f) to recognise the role of Indigenous people in the conservation and ecologically sustainable use of Australia’s biodiversity; and

(g) to promote the use of Indigenous people’s knowledge of biodiversity with the involvement of, and in cooperation with, the owners of the knowledge.

The park was declared under the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1975 (NPWC Act) which was replaced by the EPBC Act in July 2000. The park continues as a Commonwealth reserve under the EPBC Act pursuant to the Environmental Reform (Consequential Provisions) Act 1999, which deems the park to have been declared for the following purposes:

- the preservation of the area in its natural condition

- the encouragement and regulation of the appropriate use, appreciation and enjoyment of the area by the public.

The Director is a corporation under the EPBC Act (s.514A) and a Commonwealth authority for the purposes of the Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act 1997. The corporation is controlled by the person appointed by the Governor-General to the office that is also called the Director of National Parks (s.514F of the EPBC Act).

The functions of the Director (s.514B) include the administration, management and control of the park. The Director generally has power to do all things necessary or convenient for performing the Director’s functions (s.514C). The Director has a number of specified powers under the EPBC Act and EPBC Regulations, including to prohibit or control some activities, and to issue permits for activities that are otherwise prohibited. The Director performs functions and exercises powers in accordance with this plan and relevant decisions of the Uluru–Kata Tjuta Board of Management.

The Uluru–Kata Tjuta Board of Management was established under the NPWC Act in 1985 and continues under the EPBC Act. A majority of Board members must be Indigenous persons nominated by the traditional Aboriginal owners of land in the park. The functions of the Board under s.376 of the EPBC Act are:

- to make decisions relating to the management of the park that are consistent with the management plan in operation for the park; and

- in conjunction with the Director, to:

- prepare management plans for the park; and

- monitor the management of the park; and

- advise the Minister on all aspects of the future development of the park.

The EPBC Act requires the Board, in conjunction with the Director, to prepare management plans for the park. When prepared, a plan is given to the Minister for approval. A management plan is a ‘legislative instrument’ for the purposes of the Legislative Instruments Act 2003 and must be registered under that Act. Following registration the plan is tabled in each House of the Commonwealth Parliament and may be disallowed by either House on a motion moved within 15 sitting days of the House after tabling.

A management plan for a Commonwealth reserve has effect for 10 years, subject to being revoked or amended earlier by another management plan for the reserve.

See Section 2.5 in relation to EPBC Act requirements for a management plan.

The EPBC Act (ss.354 and 354A) prohibits certain actions being taken in Commonwealth reserves except in accordance with a management plan. These actions are:

- kill, injure, take, trade, keep or move a member of a native species; or

- damage heritage; or

- carry on an excavation; or

- erect a building or other structure; or

- carry out works; or

- take an action for commercial purposes.

These prohibitions, and other provisions of the EPBC Act and Regulations dealing with activities in Commonwealth reserves, do not prevent Aboriginal people from continuing their traditional

use of Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park for hunting or gathering (except for purposes of sale) or for ceremonial and religious purposes (s.359A).

The EPBC Act also does not affect the operation of s.211 of the Native Title Act 1993, which provides that holders of native title rights covering certain activities do not need authorisation required by other laws to engage in those activities (s.8 EPBC Act).

Mining operations are prohibited in Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park by the EPBC Act (ss.355 and 355A) except when authorised under a management plan.

The EPBC Regulations control, or allow the Director to control, a range of activities in Commonwealth reserves, such as camping, use of vehicles, littering, commercial activities, and research. The Director applies the Regulations subject to and in accordance with the EPBC Act and management plans. The Regulations do not apply to the Director or to wardens or rangers appointed under the EPBC Act. Activities that are prohibited or restricted by the EPBC Regulations may be carried on if they are authorised by a permit issued by the Director and/or they are carried on in accordance with a management plan or if another exception prescribed by r.12.06(1) of the Regulations applies.

Access to biological resources in Commonwealth areas is regulated under Part 8A of the EPBC Regulations. Access to biological resources is also covered by ss.354 and 354A of the EPBC Act if the resources are members of a native species and/or if access is for commercial purposes. Access is covered by r.12.10 of the EPBC Regulations if it is in the course of scientific research; in that case access must be in accordance with a management plan.

Actions that are likely to have a significant impact on ‘matters of national environmental significance’ are subject to the referral, assessment and approval provisions of Chapters 2 to 4 of the EPBC Act (irrespective of where the action is taken).

At the time of preparing this plan, the matters of national environmental significance identified in the EPBC Act relevant to Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park are:

- World Heritage properties

- National Heritage places

- nationally listed threatened species and ecological communities

- listed migratory species.

In the case of World Heritage and National Heritage places, the matter of national environmental significance protected under the EPBC Act is the listed World Heritage and the listed National Heritage values of the properties and places.

The referral, assessment and approval provisions also apply to actions on Commonwealth land that are likely to have a significant impact on the environment and to actions taken outside Commonwealth land that are likely to have a significant impact on the environment on Commonwealth land. The park is Commonwealth land for the purposes of the EPBC Act. Places on the Commonwealth Heritage List are defined as forming part of the environment for the purposes of the EPBC Act. In this case, the listed Commonwealth Heritage List values are the matter protected.

Responsibility for compliance with the assessment and approvals provisions of the EPBC Act lies with persons taking relevant ‘controlled’ actions. A person proposing to take an action that the person thinks may be or is a controlled action should refer the proposal to the Minister for the Minister’s decision whether or not the action is a controlled action. The Director of National Parks may also refer proposed actions to the Minister.

The EPBC Act also contains provisions (Part 13) that prohibit or regulate actions in relation to listed threatened species and ecological communities, listed migratory species, cetaceans (whales and dolphins) and listed marine species. Appendix F to this plan identifies species in the park that are listed as threatened under the EPBC Act and Northern Territory legislation, and Appendix G identifies migratory species that are listed under the EPBC Act and under international conventions, treaties and agreements at the time of preparing this plan.

As noted above, the listed World Heritage, National Heritage and Commonwealth Heritage values of the park are protected under the EPBC Act.

Sections 313 to 324 of the EPBC Act provide for the protection of World Heritage properties, including the protection of values and the requirements for management, including the preparation of management plans. As required by the Act, Australia’s obligations in relation to the park under the World Heritage Convention have been taken into account in preparation of this management plan for the park.

In addition to the protection provided to the park by the EPBC Act as a World Heritage property, the park is listed on both the National Heritage List and the Commonwealth Heritage List under the EPBC Act.

In terms of National and Commonwealth Heritage listed places, the EPBC Act heritage protection provisions (ss.324A to 324ZC and ss.341A to 341ZH) relevantly provide:

- for the establishment and maintenance of a National Heritage List and a Commonwealth Heritage List, criteria and values for inclusion of places in either list and management principles for places that are included in the two lists

- that Commonwealth agencies must not take an action that is likely to have an adverse impact on the heritage values of a place included in either list unless there is no feasible and prudent alternative to taking the action, and all measures that can reasonably be taken to mitigate the impact of the action on those values are taken

- that Commonwealth agencies that own or control places must:

i. make a written plan to protect and manage the Commonwealth Heritage values of each of its Commonwealth Heritage places;

ii. prepare a written heritage strategy for managing those places to protect and conserve their Commonwealth Heritage values, addressing any matters required by the EPBC Regulations, and consistent with the Commonwealth Heritage management principles; and

iii. identify Commonwealth Heritage values for each place, and produce a register that sets out the Commonwealth Heritage values (if any) for each place (and do so within the time frame set out in their heritage statements).

The prescriptions within this management plan are consistent with World Heritage, National Heritage and Commonwealth Heritage management principles and other relevant obligations under the EPBC Act for protecting and conserving the heritage values for which the park has been listed.

Civil and criminal penalties may be imposed for breaches of the EPBC Act.

2.5 Purpose, content and matters to be taken into account in a

management plan

The purpose of this management plan is to describe the philosophy and direction of management for the park for the next 10 years in accordance with the EPBC Act. The plan enables management to proceed in an orderly way; it helps reconcile competing interests and identifies priorities for the allocation of available resources.

Under s.367(1) of the EPBC Act, a management plan for a Commonwealth reserve (in this case, the park) must provide for the protection and conservation of the reserve. In particular, a management plan must:

(a) assign the reserve to an IUCN protected area category (whether or not a Proclamation has assigned the reserve or a zone of the reserve to that IUCN category); and

(b) state how the reserve, or each zone of the reserve, is to be managed; and

(c) state how the natural features of the reserve, or of each zone of the reserve, are to be protected and conserved; and

(d) if the Director holds land or seabed included in the reserve under lease—be consistent with the Director’s obligations under the lease; and

(e) specify any limitation or prohibition on the exercise of a power, or performance of a function, under the EPBC Act in or in relation to the reserve; and

(f) specify any mining operation, major excavation or other work that may be carried on in the reserve, and the conditions under which it may be carried on; and

(g) specify any other operation or activity that may be carried on in the reserve; and

(h) indicate generally the activities that are to be prohibited or regulated in the reserve, and the means of prohibiting or regulating them; and

(i) indicate how the plan takes account of Australia’s obligations under each agreement with one or more other countries that is relevant to the reserve (including the World Heritage Convention and the Ramsar Convention, if appropriate); and

(j) if the reserve includes a National Heritage place:

(i) not be inconsistent with the National Heritage management principles; and

(ii) address the matters prescribed by regulations made for the purposes of paragraph 324S(4)(a); and

(k) if the reserve includes a Commonwealth Heritage place:

(i) not be inconsistent with the Commonwealth Heritage management principles; and

(i) address the matters prescribed by regulations made for the purposes of paragraph 341S(4)(a).

In preparing a management plan the EPBC Act (s.368) also requires account to be taken of various matters. In respect to Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park these matters include:

- the regulation of the use of the park for the purpose for which it was declared

- the interests of:

- the traditional owners of the park

- any other Indigenous persons interested in the park

- any person who has a usage right relating to land, sea or seabed in the park that existed (or is derived from a usage right that existed) immediately before the park was declared

- the protection of the special features of the park, including objects and sites of biological, historical, palaeontological, archaeological, geological and geographical interest

- the protection, conservation and management of biodiversity and heritage within the park

- the protection of the park against damage

- Australia’s obligations under agreements between Australia and one or more other countries relevant to the protection and conservation of biodiversity and heritage.

2.6 IUCN category and zoning

In addition to assigning a Commonwealth reserve to an IUCN protected area category, a management plan may divide a Commonwealth reserve into zones and assign each zone to an IUCN category. The category to which a zone is assigned may differ from the category to which the reserve is assigned (s.367(2)).

The provisions of a management plan must not be inconsistent with the management principles for the IUCN category to which the reserve or a zone of the reserve is assigned (s.367(3)). See Section 3 for information on Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park’s IUCN category.

2.7 Lease agreement

The park is owned by the Uluru–Kata Tjuta Aboriginal Land Trust (representing Ngurarita) and leased to the Director of National Parks as a national park. The Lease expires on 25 October 2084. With the exception of the term, the provisions of the Lease may be reviewed by the Land Trust, the Central Land Council and the Director every five years, or at any agreed time. Five years before the Lease expires the Land Trust and the Director will negotiate for its renewal or extension. The Land Trust and the Director may agree in writing to terminate the Lease at any time.

If any legislation enacted in connection with the park is inconsistent with the Lease and substantially detrimental to the Land Trust or to ‘relevant Aboriginals’ in terms of the park’s administration, management or control, the Lease is deemed to be breached. Such action may lead to termination of the Lease on 18 months’ notice being given by the Land Trust, subject to an obligation to negotiate bona fide with a view to a new lease being granted.

Under the Lease the following rights of ‘relevant Aboriginals’ are reserved, subject to the directions or decisions of the Board and any such reasonable constraints mentioned within the management plan:

- the right to enter, use and occupy the park in accordance with Aboriginal tradition

- the right to continue to use the park for hunting and food gathering and for ceremonial and religious purposes

- the right to reside in the park in the vicinity of the present Mutitjulu Community or at other locations as may be specified in the management plan.

The Director’s responsibilities under the Lease include:

- at the request of the Land Trust, sub-letting any reasonable part of the park to the Mutitjulu Community Aboriginal Corporation (MCAC) or other relevant Aboriginal association that replaces the corporation provided the sublease is in accordance with the EPBC Act, the Land Rights Act and the management plan

- paying rent to the Central Land Council on behalf of the Land Trust. (At the time of preparing this plan the rent is $150,000 per year, indexed from May 1990, plus an amount equal to 25 per cent of park revenue)

- complying with the EPBC Act and Regulations, other laws and the plan and managing the park in accordance with world best practice

- promoting and protecting the interests of ‘relevant Aboriginals’ and their Aboriginal traditions and areas of significance and promoting Aboriginal administration, management and control of the park

- promoting the employment and training of ‘relevant Aboriginals’

- promoting understanding of and respect for Aboriginal traditions, languages, cultures, customs and skills

- consulting the Central Land Council and the relevant Aboriginal association (currently MCAC) about management of the park

- encouraging Aboriginal business and commercial enterprises

- providing funding to MCAC to employ a community liaison officer

- providing maintenance of roads and other facilities

- implementing a licensing scheme for tour operators

- properly collecting and auditing entrance fees and other charges

- funding the administration of the Board of Management

- maintaining specified staffing arrangements

- restricting public access to areas of the park for the purpose of Aboriginal use of these areas

- assisting the Central Land Council in identifying and recording sacred sites in the park

- exchanging research information with the Central Land Council.

The full provisions of the Lease at the time of preparing this plan are at Appendix A.

2.8 International agreements

This management plan must take account of Australia’s obligations under relevant international agreements. The following agreements are relevant to the park and are taken into account in this management plan.

World Heritage Convention

The World Heritage Convention is an international agreement which encourages countries to ensure the protection of their natural and cultural heritage which has outstanding universal value. The convention aims to define and conserve the world’s most outstanding heritage places by drawing up a list of sites whose outstanding universal value should be preserved for all humanity and to ensure their protection through cooperation among nations. Parties to the Convention undertake to identify, protect, conserve, present and transmit to future generations the World Heritage sites on their territory.

Australia was one of the first countries in the world to ratify the convention, which came into force in 1975. At the time of preparing this plan, the park is one of only 25 World Heritage sites listed for both its natural and cultural heritage.

The listing of Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park as a World Heritage Cultural Landscape provides international recognition of Tjukurpa as a major religious philosophy which links Anangu to their environment. Appendix B summarises the park’s World Heritage criteria and attributes.

In 1995 the Director and the Uluru–Kata Tjuta Board of Management were awarded the Picasso Gold Medal, UNESCO’s highest award, for outstanding efforts to preserve the landscape and Anangu culture and for setting new international standards for World Heritage management.

CAMBA

CAMBA provides for China and Australia to cooperate in the protection of migratory birds listed in the annex to the agreement and their environment, and requires each country to take appropriate measures to preserve and enhance the environment of migratory birds. Thirteen species listed under this agreement occur in the park.

JAMBA

JAMBA provides for Japan and Australia to cooperate in taking measures for the management and protection of migratory birds, birds in danger of extinction, and the management and protection of their environments, and requires each country to take appropriate measures to preserve and enhance the environment of birds protected under the provisions of the agreement. Fourteen species listed under this agreement occur in the park.

ROKAMBA

ROKAMBA provides for the Republic of Korea and Australia to cooperate in taking measures for the management and protection of migratory birds and their habitat by providing a forum for the exchange of information, support for training activities and collaboration on migratory bird research and monitoring activities. Twelve species listed under this agreement occur in the park.

Bonn Convention

The Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (Bonn Convention) aims to conserve terrestrial, marine and avian migratory species throughout their range. Parties to this convention work together to conserve migratory species and their habitats. Eleven species listed under this convention occur in the park.

Species that are listed under the above migratory agreements and conventions are listed species under Part 13 of the EPBC Act. Appendix G to this management plan describes listed migratory species found in the park.

UNESCO Man and the Biosphere Programme

In January 1977 Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park was accepted as a biosphere reserve under the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Man and the Biosphere Programme, an international network of biosphere reserves that aims to protect and preserve examples of the world’s major ecosystem types.

Part 2 – How the park will be managed

3. IUCN category

3.1 Assigning the park to an IUCN category

Our aim

The park is managed in accordance with a designated IUCN protected area category and relevant management principles.

Measuring how well we are meeting our aim

- Degree of compliance of management with the relevant Australian IUCN reserve management principles.

Background

Nganana National park tjukarurungku atunymankupai.

© Tony Tjamiwa

We are protecting this national park according to our Law. ©

As noted in Section 2.6, the EPBC Act requires this management plan to assign the park to an IUCN category. The EPBC Regulations prescribe the management principles for each IUCN category. The category to which the park is assigned is guided by the purposes for which the park was declared (see Section 2.4, Legislative context). The purposes for which Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park was declared are consistent with the characteristics for IUCN protected area category II ‘national park’.

What we are going to do

3.1.1 The park is assigned to IUCN protected area category II ‘national park’ and will be managed in accordance with the management principles set down in Schedule 8 of the EPBC Regulations and listed in Appendix H:

- Natural and scenic areas of national and international significance should be protected for spiritual, scientific, educational, recreational or tourist purposes.

- Representative examples of physiographic regions, biotic communities, genetic resources, and native species should be perpetuated in as natural a state as possible to provide ecological stability and diversity.

- Visitor use should be managed for inspirational, educational, cultural and recreational purposes at a level that will maintain the reserve or zone in a natural or near natural state.

- Management should seek to ensure that exploitation or occupation inconsistent with these principles does not occur.

- Respect should be maintained for the ecological, geomorphologic, sacred and aesthetic attributes for which the reserve or zone was assigned to this category.

- The needs of Indigenous people should be taken into account, including subsistence resource use, to the extent that they do not conflict with these principles.

- The aspirations of traditional owners of land within the reserve or zone, their continuing land management practices, the protection and maintenance of cultural heritage and the benefit the traditional owners derive from enterprises established in the reserve or zone, consistent with these principles, should be recognised and taken into account.

4. Joint management

Joint management is Nguraritja and Parks Australia working together, consulting and sharing decision-making to manage the park. Joint management is based on mutual trust and respect, working together as equals, and sharing knowledge. At the heart of joint management for Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park is the commitment to look after country and culture by keeping Tjukurpa strong and meeting obligations under Piranpa law. Joint management also aims to ensure visitors have the best opportunity to enjoy, share in and appreciate the park and Anangu culture. |

4.1 Making decisions and working together

Our aim

The park is managed to the highest standards for protection of natural and cultural values and provision of quality visitor experiences and for Nguraritja to meet their obligations to country and satisfy their aspirations for benefits from land ownership. Parks Australia and Nguraritja will work together to make shared and informed, consistent, transparent and accountable decisions.

Measuring how well we are meeting our aim

- Extent to which natural and cultural values are conserved by maintaining abundance and distribution of significant species and ongoing protection of cultural values.

- Percentage of visitors who give positive feedback about their experience.

- Level of increase in the number of Anangu who are employed directly or indirectly within the park.

- Extent to which the Board feels that obligations to country are being met.

- Extent of opportunities provided for intergenerational transfer of Anangu knowledge and skills related to maintaining the cultural landscape.

- Level of Board satisfaction that the Director and Nguraritja are working together to make shared and informed, consistent, transparent and accountable decisions.

Background

Law Kutjaraku ngaranyi tjunguringkunytjaku munu pula ara tjutangka wirura ngaranytjaku. Law kutjara watalpi tjunguringu munulta kuwari ngaranyi kunpuntjaku kutju. Mara Kutjara tjunguringkula pulkara kunpungku witini.

© Tony Tjamiwa

There are two laws to be joined and both sets of law need to be properly respected. The two laws have been brought together already and now only the bond needs to be strengthened - like two interlocking hands really strongly held together. ©

The Director of National Parks and Nguraritja have entered into an agreement to jointly manage the park. Joint management is based on Aboriginal title to the land through the Land Rights Act and on the Lease between the Director and the Uluru–Kata Tjuta Aboriginal Land Trust, which