COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA

Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999

APPROVAL OF THE KAKADU NATIONAL PARK

MANAGEMENT PLAN 2016-2026

I, JAMIE BRIGGS, Minister for Cities and the Built Environment, acting pursuant to section 370 of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, hereby approve the Kakadu National Park Management Plan 2016-2026.

Dated this …25... day of …November…, 20 ..15..

JAMIE BRIGGS……………………………

Jamie Briggs

Minister for Cities and the Built Environment

[THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY BLANK – INSIDE COVER]

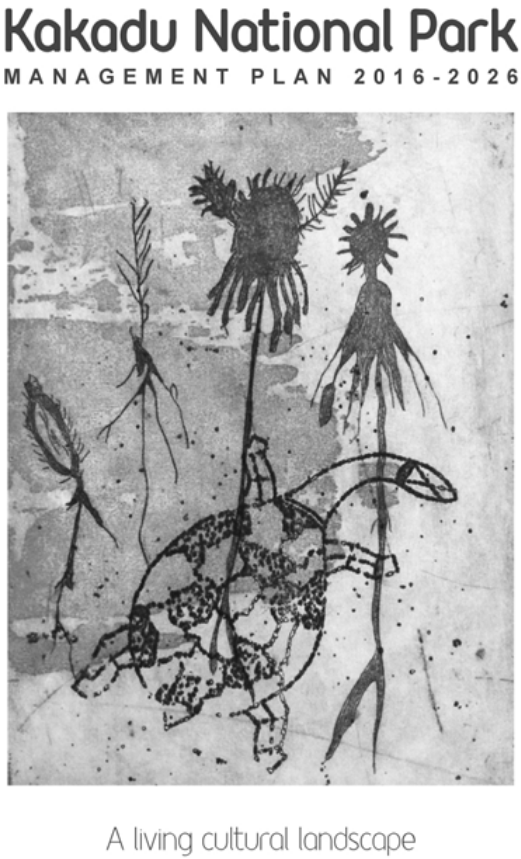

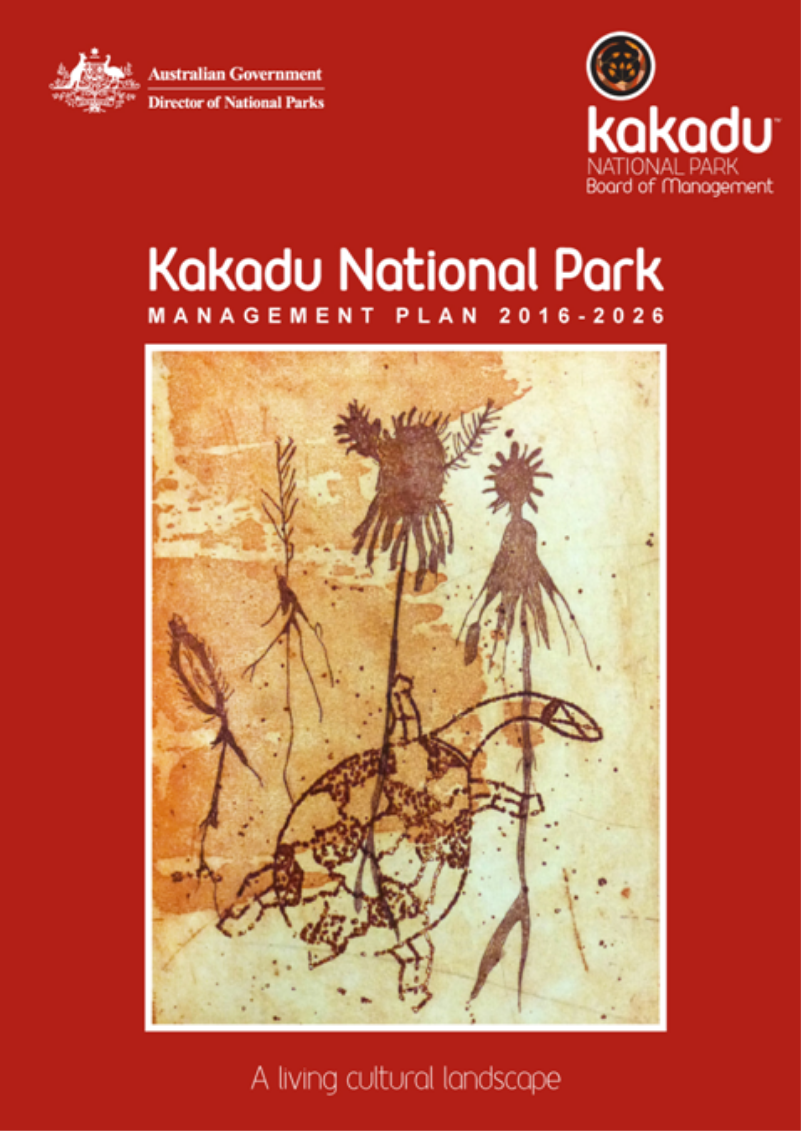

The artwork appearing on the cover of this plan was created by Ina Brown ©

Al-mangeyi

‘This is a picture of an Al-mangeyi (a long neck turtle).

I go hunting for them with my family in the dry season.

My favourite place to hunt for turtle is the Mamukala wetlands.

We use a crow bar to find them in the mud, then we cook them in the coals.’

The cover artwork was created during

The cover artwork was created during

Children’s Ground printmaking workshops

as part of the developing Bininj Kunwaral

Arts Enterprise.

ISBN: 978-0-9807460-7-5 (Print)

ISBN: 978-0-9807460-6-8 (Online)

© Director of National Parks 2016

This plan is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Director of National Parks. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to:

Director of National Parks

GPO Box 787

Canberra ACT 2601

Director of National Parks Australian business number: 13051 694 963

This management plan sets out how it is proposed the park will be managed for the next 10 years.

A copy of this plan is available online at:

www.environment.gov.au/topics/national-parks/parks-australia/publications.

.

Foreword

Kakadu National Park is, and always has been, Bininj/Mungguy land. The evidence for this is in the World Heritage rock art and archaeological sites throughout the park and Bininj/Mungguy people’s traditional connection to their land and culture. The long and continuing history of Bininj/Mungguy custodianship of Kakadu is one of the most important things about the park, recognised in its World Heritage listing.

Traditional owners and managers of Kakadu have strong responsibilities and obligations to care for country and to guide and look after visitors.

From the late 1970s to the time of preparing this plan, about half of the park has been granted as Aboriginal land under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 and the traditional owners have leased back the land to the Director of National Parks to be managed as part of Kakadu National Park. The remaining half of the park may become Aboriginal land during the life of this plan and will also be leased to the Director of National Parks.

Since the park was declared, it has been managed as if it was all Aboriginal land. Through joint management, Bininj/Mungguy have worked hard with the Director of National Parks and park staff to balance the protection of their culture with making the park an outstanding destination for visitors.

The Kakadu National Park Board of Management wrote this management plan. When writing this plan, the Board worked together to:

- decide on the most important values to recognise and protect in the plan

- decide on the most significant issues impacting those values and to provide instructions on how those issues should be dealt with

- provide ways to make sure Bininj/Mungguy are involved in the implementation of the plan

- provide ways to make sure that the things they have said will be done are done and to measure how well they are done.

The plan sets out how Kakadu National Park is to be managed over the next 10 years.

Kakadu National Park Board of Management

Purpose

Purpose

Kakadu National Park was established for the following purposes:

- the preservation of the area in its natural condition

- the encouragement and regulation of the appropriate use, appreciation and enjoyment of the area by the public.

The vision for Kakadu National Park is that it continues to be one of the great World Heritage areas, recognised internationally as a place where:

- the cultural and natural values of the park are protected and Bininj/Mungguy culture is respected

- Bininj/Mungguy guide and are involved in all aspects of managing the park

- knowledge about country and culture is passed on to younger Bininj/Mungguy, and future generations of Bininj/Mungguy have the option to stay in the park to look after country

- world-class visitor experiences are provided, and tourism is conducted in culturally, environmentally, socially and economically sustainable ways

- disturbed areas are rehabilitated and reintegrated into the park

- Bininj/Mungguy gain sustainable social and economic outcomes from the park.

Guiding principles

The guiding principles for the management of Kakadu National Park are that:

- culture, country, sacred places and customary law are one, extend beyond the boundaries of Kakadu, and need to be protected and respected

- Bininj/Mungguy and Balanda keep joint management strong by working together, communicating effectively and sharing decision-making

- consultation with Bininj/Mungguy is conducted appropriately and with

the right people for that country - everyone who lives and works in the park learns from, understands and respects each other

- young Bininj/Mungguy have opportunities to learn about their culture and country

- Bininj/Mungguy and park management maintain and respect each other’s obligations

and work together to look after the natural and cultural values of the park - the progress and development of tourism are undertaken in accordance with the wishes of Bininj/Mungguy, and strong partnerships are maintained with the tourism industry

- visitors are provided with opportunities for safe, enriching and memorable experiences.

The Kakadu Board of Management is grateful to the many individuals and organisations that contributed to this management plan. In particular they acknowledge Bininj/Mungguy, Parks Australia staff, the Northern Land Council, and the Northern Territory and Australian Government agencies that provided information and assistance or submitted contributions that contributed to the development of this management plan.

Members of the Kakadu Board of Management involved in preparing this plan

Frear Alderson Murrumburr clan (Deputy member)

Michael Bangalang Murruwan clan

Sally Barnes Director of National Parks (from June 2014)

Ryan Baruwei Wurrkbarbar (Jawoyn) clan (Chair from 2012 to 2014)

Peter Cochrane Director of National Parks (to December 2013)

Victor Cooper Minitja clan (Deputy member)

Michael Douglas Nature conservation (from 2014)

Melanie Elgregbud Mirarr/Gundjeihmi clan (Deputy member)

Joshua Hunter Wurrkbarbar (Jawoyn) clan (resigned June 2014)

Graham Kenyon Limilngan clan

Violet Lawson Murrumburr clan

Jeffrey Lee Djok clan

Maria Lee Wurrkbarbar (Jawoyn) clan (Chair from 2014)

Yvonne Margarula Mirarr/Gundjeihmi clan

Mick Markham Bolmo clan (Jawoyn) (Chair to 2012)

Tony Mayell Northern Territory Government (from November 2013)

Anna Morgan Assistant Secretary, Parks Australia

Rick Murray Tourism industry

Jonathan Nadji Bunitdj clan (Deputy Chair)

Alfred Nayinggul Maniligar clan

Denise Williams Wurrkbarbar (Jawoyn) clan (Deputy member)

Henry Yates Limilngan clan (Deputy member)

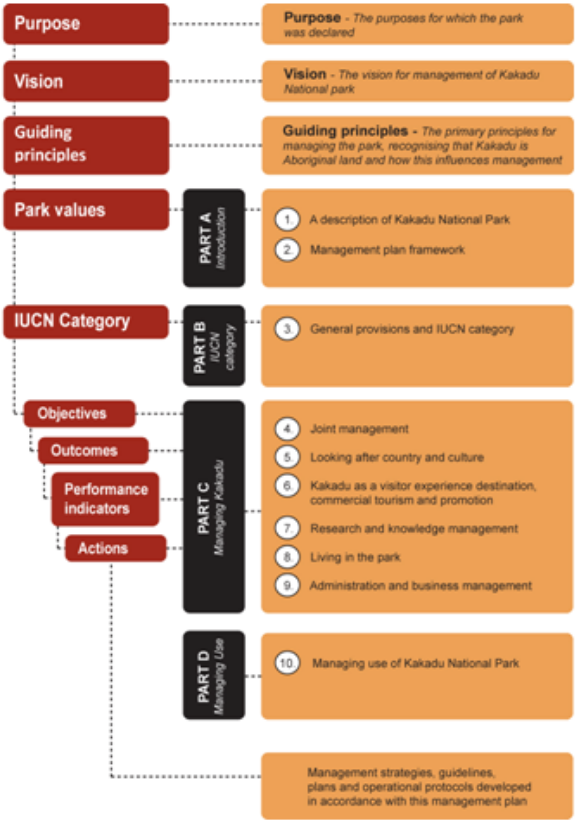

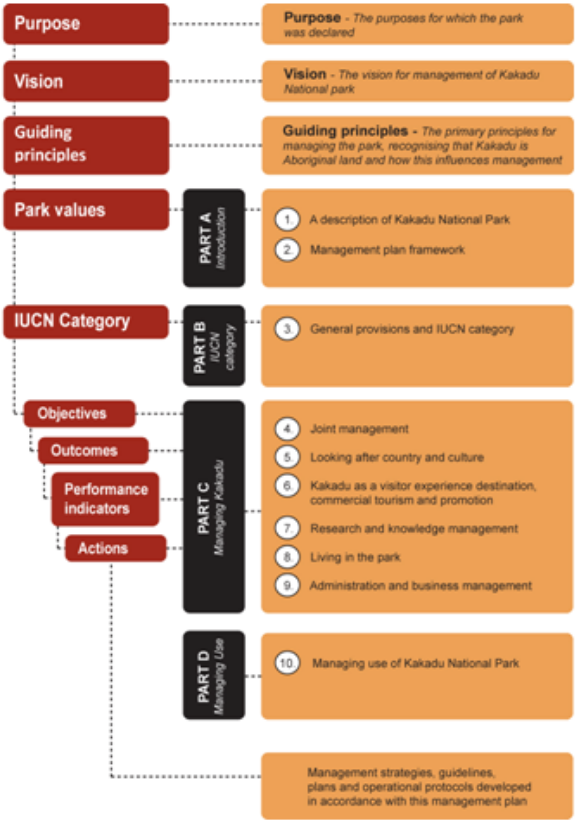

How to read this plan

This management plan takes a different approach to previous management plans for Kakadu National Park. The approach uses the park values statement (see Table 1) to establish the policies and actions needed to protect, present and understand the values of the park over the life of the plan, consistent with the purposes for which the park is established.

This plan also differentiates the actions the Director of National Parks can and will take over the life of the plan to protect, present and understand park values from the rules that apply to activities by park visitors and users; hence it is structured in two discrete parts:

- Managing Kakadu: This part of the plan is structured around joint management, protecting the cultural and natural values of the park, developing and promoting Kakadu as a visitor destination, and increasing our understanding of the park’s values. It sets out policies that will apply to the Director’s activities over the life of the plan as well as describing the actions that will be taken towards achieving the outcomes described in the plan. Any policies relating to provisions of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Regulations 2000 (EPBC Regulations) that specifically apply to the activities of the Director in managing the park are also described.

- Managing use of Kakadu: This part of the plan is structured around how the Director will enable and manage appropriate visitor and stakeholder activities in the park in accordance with the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) and EPBC Regulations. It sets out any policies that apply to park users. Policies include those related to provisions in the EPBC Regulations as well as those that more broadly protect the park values or contribute to the effective management of the park.

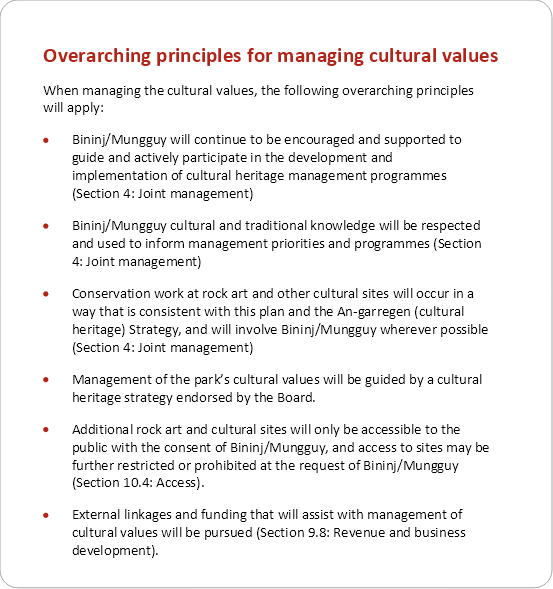

This plan takes a more strategic approach than previous plans. To enable this, each section relating to protecting and presenting park values starts with a set of overarching principles which apply to the management of all aspects of that section. More detailed policies and actions relating to a particular issue are then outlined in the relevant subsections.

Some readers of this plan may find that information which was previously in a single section of the plan is now dealt with in a number of sections, or that material which was previously dispersed across the plan is now in a single section. When looking for particular actions or policies, readers should consider whether they are seeking information on what the Director of National Parks will do over the life of the plan or whether they are seeking information about park visitor and user activities.

Bininj/Mungguy

Throughout this plan the term Bininj/Mungguy is used to refer to the traditional Aboriginal owners of Aboriginal land in the park (within the meaning of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976) and other Aboriginals entitled by Aboriginal tradition to use or occupy land in the park (whether or not the traditional entitlement is qualified as to place, time, circumstance, purpose or permission).

Bininj is a Kunwinjku and Gundjeihmi word, pronounced ‘bin-ing’. This word is similar to the English word ‘man’ and can mean man, male, person or Aboriginal people, depending on the context. The word for woman in these languages is Daluk. Other languages in Kakadu National Park have other words with these meanings – for example the Jawoyn word for man is Mungguy and for woman is Alumka, and the Limilngan word for man is Murlugan and for woman is Ugin-j.

The Kakadu National Park Board of Management has agreed to use the term Bininj/Mungguy for the purposes of this management plan.

Contents

Foreword......................................................i

Purpose......................................................iii

Vision.......................................................iii

Guiding principles...............................................iii

Acknowledgements..............................................iv

How to read this plan.............................................V

Bininj/Mungguy.................................................V

Part A - Introduction.............................................1

1. A description of Kakadu National Park.............................2

1.1 Kakadu – a brief description.................................2

1.2 The Aboriginal custodians...................................2

1.3 Establishment of Kakadu National Park..........................5

1.4 Park values and local, regional, national and international significance.....9

1.5 Joint management.......................................16

2. Management plan framework..................................17

2.1 Management planning process..............................17

2.2 The planning framework...................................18

Part B – General provisions and IUCN Category...........................23

3. General provisions and IUCN category............................24

3.1 Short title.............................................24

3.2 Commencement and termination.............................24

3.3 Interpretation.........................................24

3.4 IUCN category..........................................24

Part C - Managing Kakadu.........................................27

4. Joint management..........................................28

4.1 Making decisions and working together (Board of Management).........30

4.2 Making decisions and working together (on country).................35

4.3 Bininj/Mungguy training and other opportunities...................38

5. Looking after culture and country................................41

5.1 Looking after culture......................................41

5.2 Looking after country......................................57

5.3 Managing park-wide threats affecting values.....................75

6. Kakadu as a visitor experience destination, commercial tourism

and promotion............................................99

6.1 Destination and visitor experience development..................101

6.2 Commercial tourism development and management.................106

6.3 Promotion and marketing...................................108

6.4 Visitor information.......................................110

7. Research and knowledge management...........................113

7.1 Research and knowledge management........................115

8. Living in the park – Jabiru and outstations.........................118

8.1 Outstations and living on country............................118

8.2 Jabiru..............................................120

9. Administration and business management.........................125

9.1 Safety and incident management.............................125

9.2 Compliance and enforcement.............................129

9.3 Authorising and managing activities.........................131

9.4 Capital works and infrastructure.............................133

9.5 Assessment of proposals..................................135

9.6 Resource use in park operations.............................140

9.7 Neighbours, stakeholders and partnerships......................142

9.8 Revenue and business development...........................144

9.9 Carrying out and authorising activities not otherwise specified

and new ways of authorising activities.........................146

9.10 Implementing and evaluating the plan.........................147

Part D – Managing Use Of Kakadu....................................151

10. Managing use of Kakadu National Park.............................152

10.1 Authorisation of allowable activities............................153

10.2 General rules for managing use of the park.......................155

10.3 Living in the park (outstations and Jabiru).......................157

10.4 Access...............................................162

10.5 Commercial use of resources................................165

10.6 Traditional use of land and water.............................168

10.7 Recreational activities....................................170

10.8 Commercial tourism and accommodation.......................175

10.9 Filming and photography (and other commercial image capture)........178

10.10 Commercial fishing......................................179

10.11 Infrastructure and works..................................180

10.12 Research and monitoring activities and access to genetic resources......181

10.13 Bringing plants, animals and other materials into the park............184

Appendices..................................................187

Appendix A: World Heritage attributes...............................188

Appendix B: Ramsar criteria......................................192

Appendix C: International agreements...............................193

Appendix D: EPBC-listed migratory species recorded in Kakadu National Park.....195

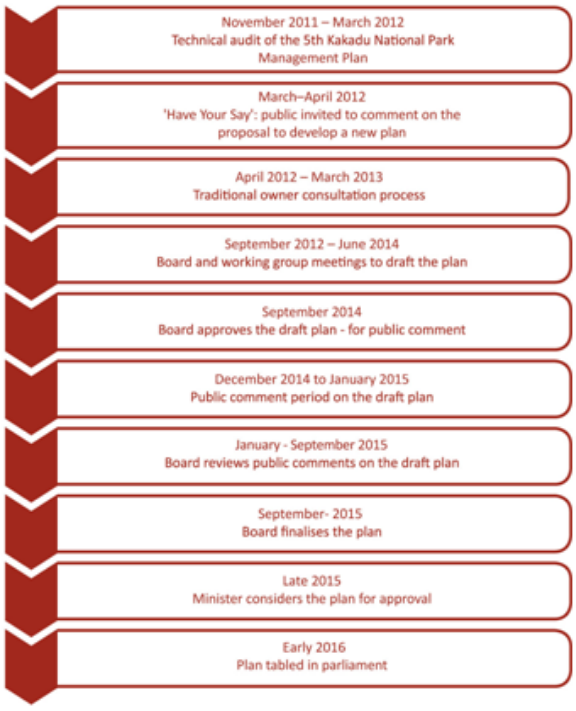

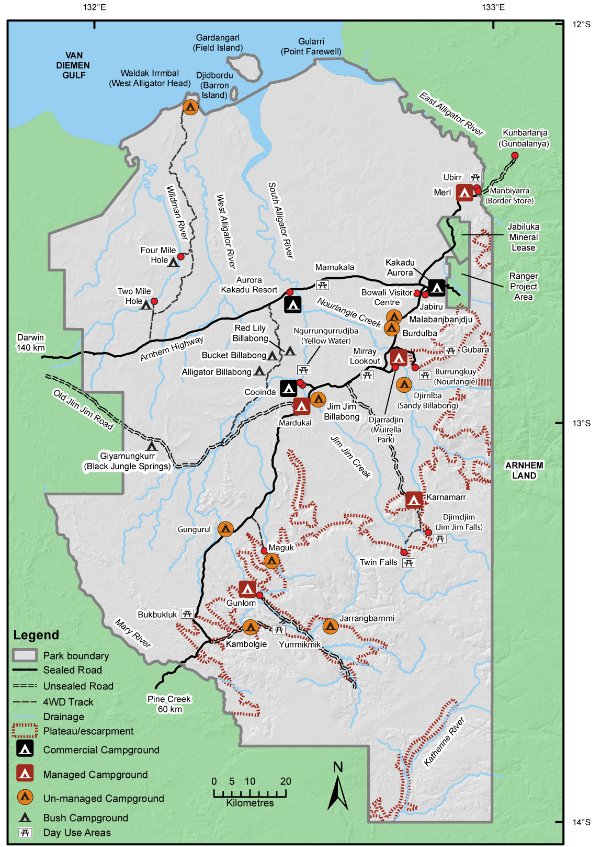

Appendix E: Summary of the timeframes and consultation process

used in developing this plan..............................198

Appendix F: Glossary and interpretation..............................201

Appendix G: Legislative context....................................208

Appendix H: IUCN administrative and management principle schedules...........216

Appendix I: Provisions of leases.....................................220

Appendix J: Species of conservation concern...........................241

Bibliography...................................................245

Map data sources..............................................248

Tables

Table 1: Kakadu National Park Values Statement 10

Table 2: Focus of management for the protection of park values 21

Table 3: Guide to decision-making 34

Table 4: Impact assessment process 137

Table 5: Environmental impact assessment matters and considerations 138

Table 6: Key EPBC requirements for access to biological resources

as they concern the park 183

Figures

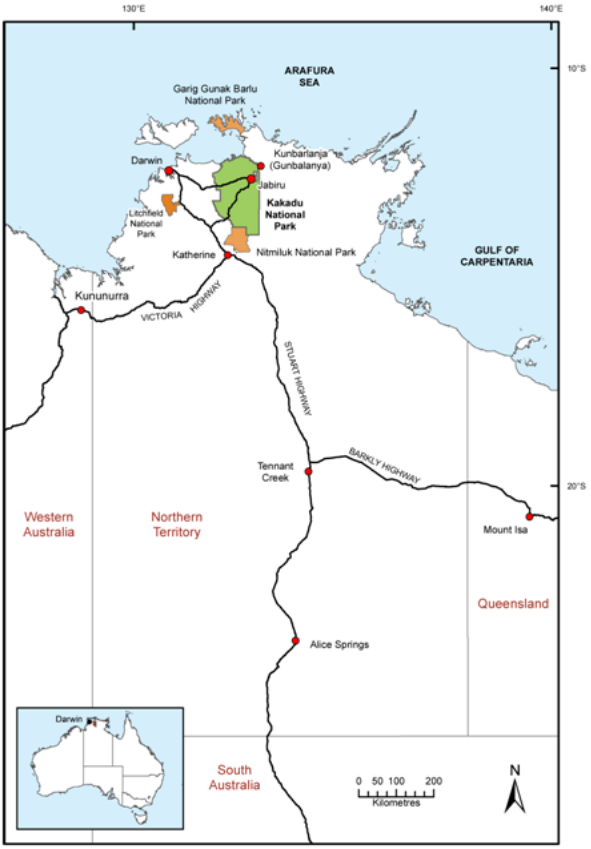

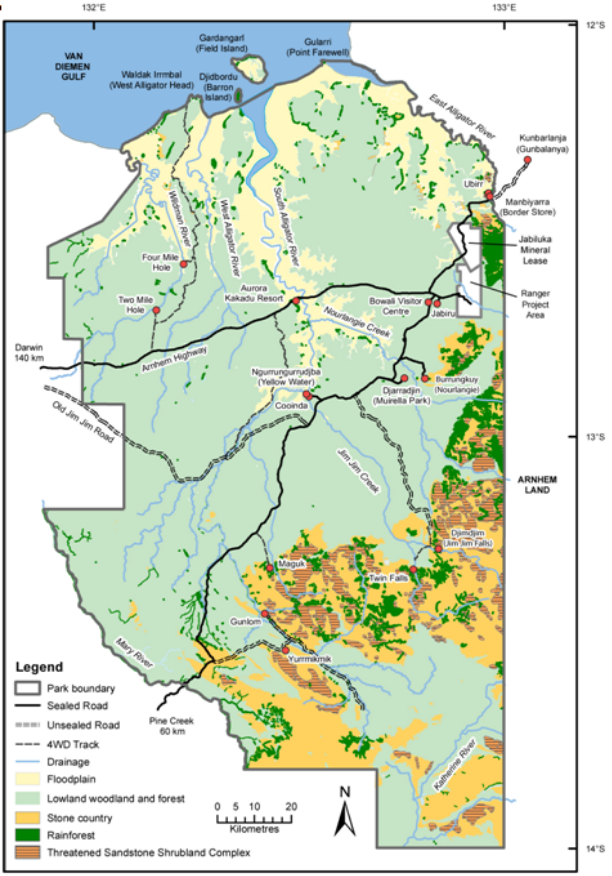

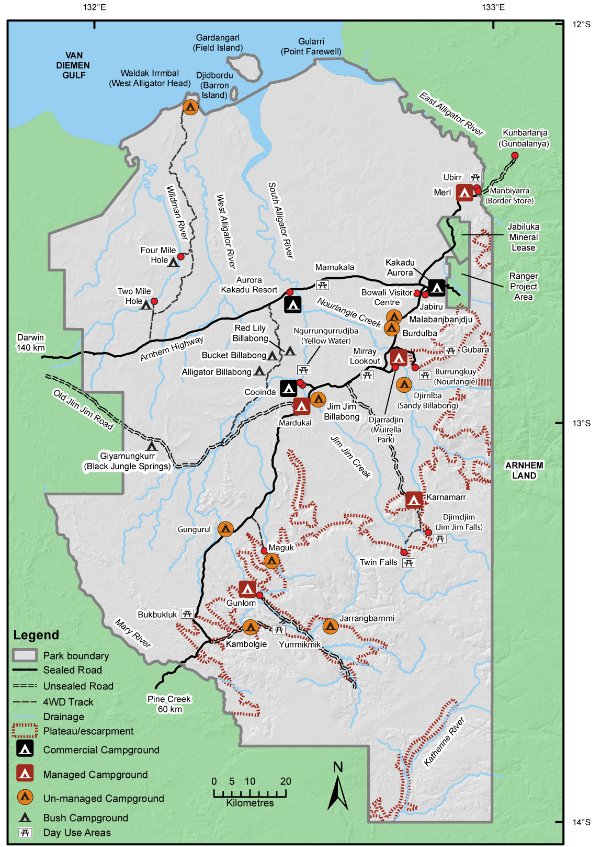

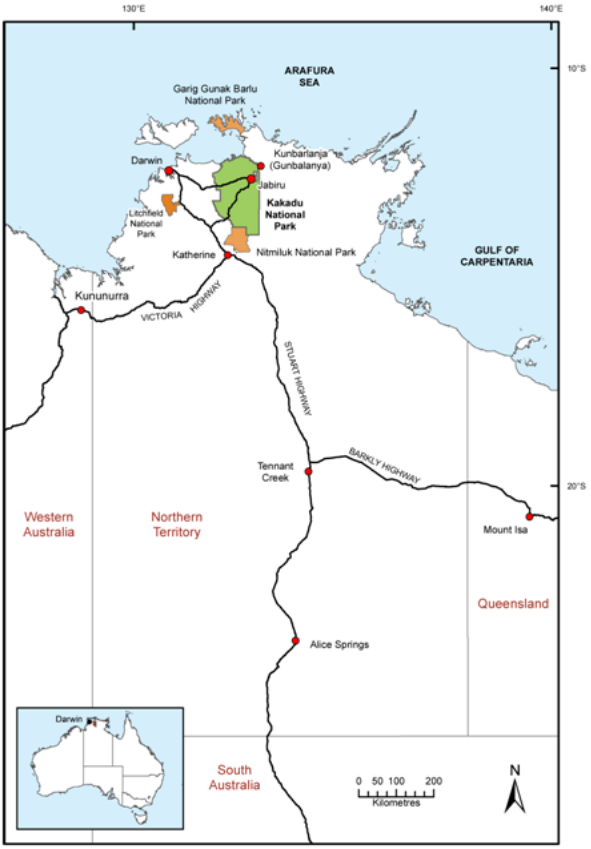

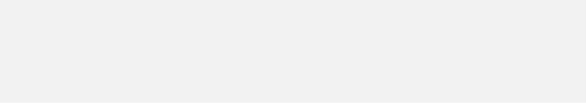

Figure 1 Location of Kakadu National Park 3

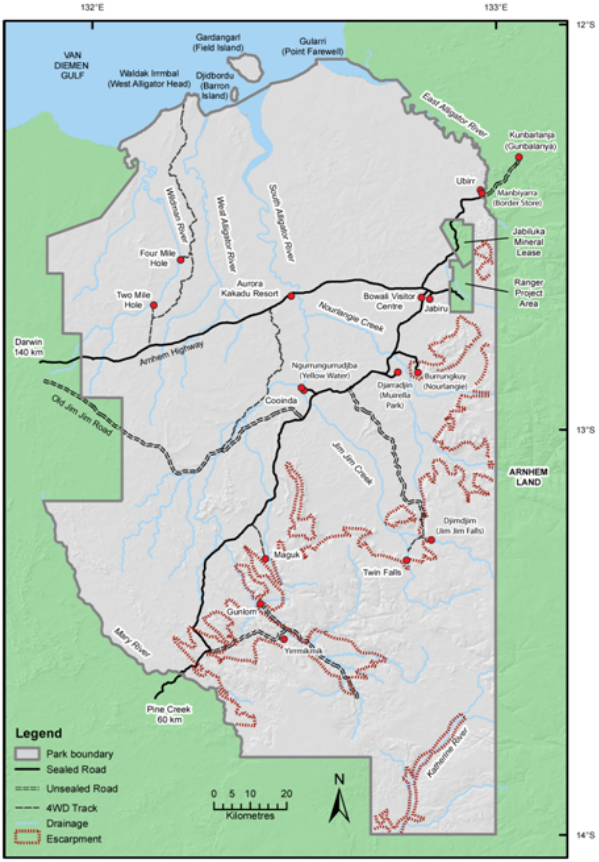

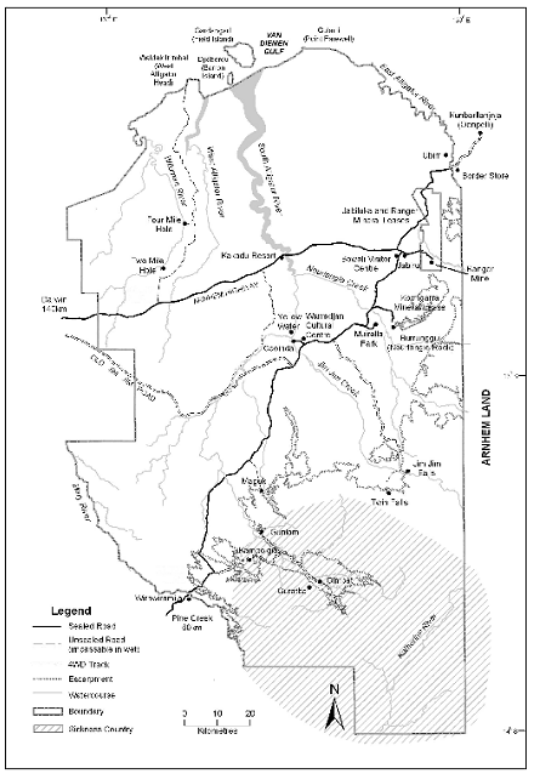

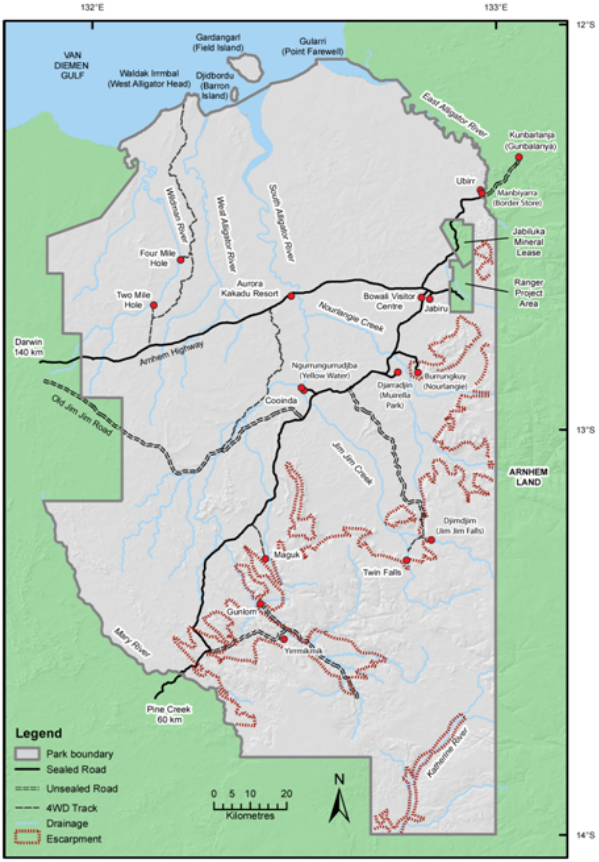

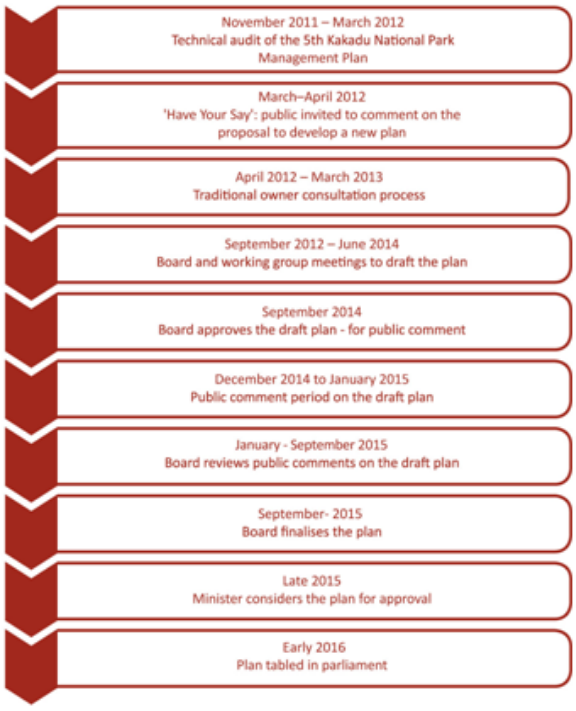

Figure 2: Kakadu National Park 6

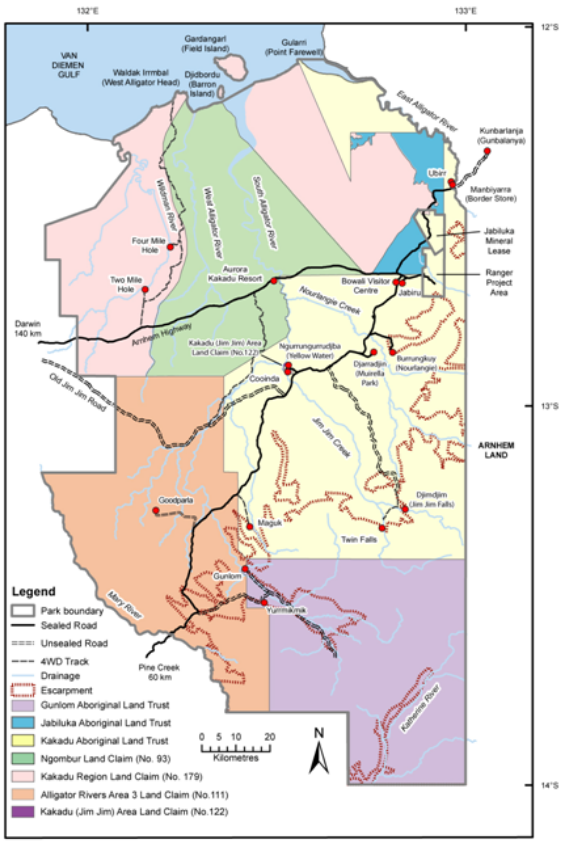

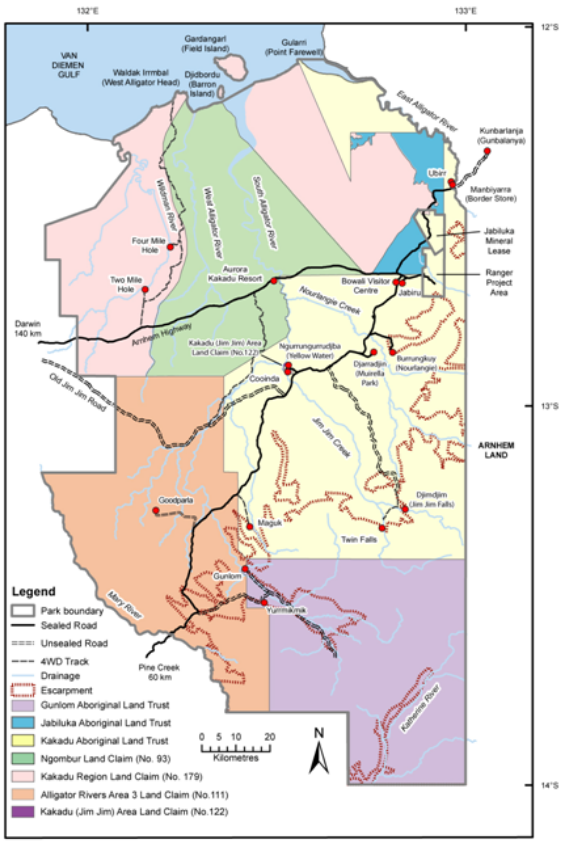

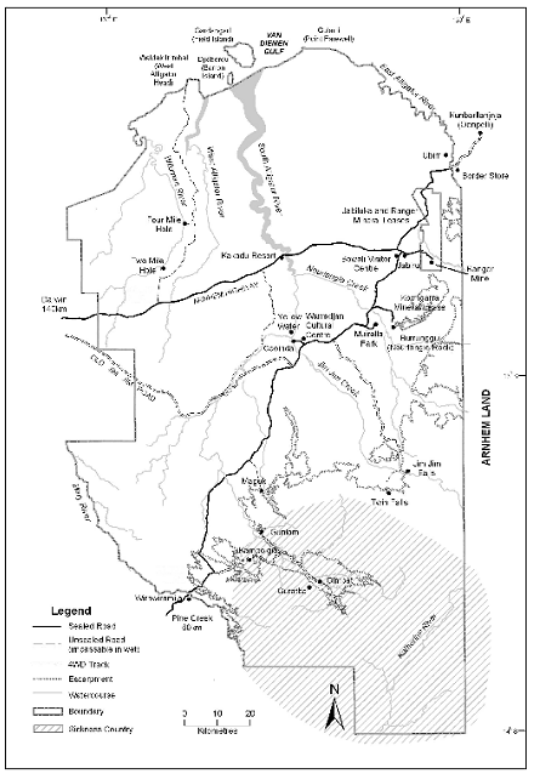

Figure 3: Aboriginal land and land claims in Kakadu National Park as at April 2014 8

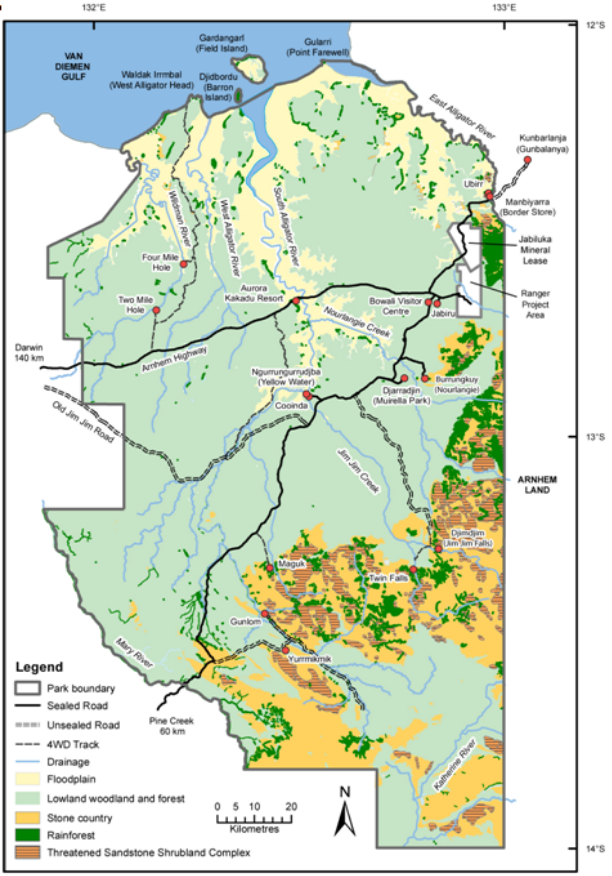

Figure 4: Kakadu’s major landscapes 14

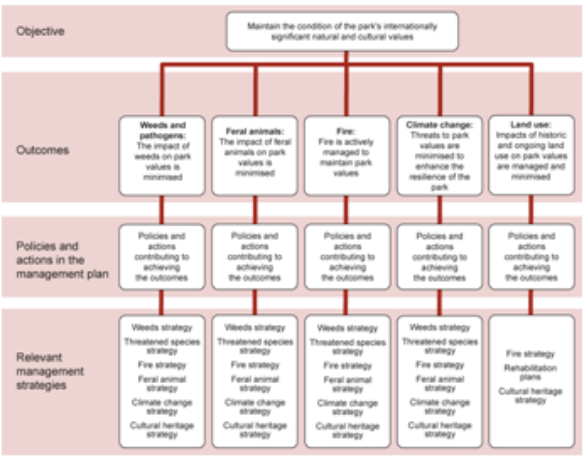

Figure 5: Conceptual framework for the structure of this plan 20

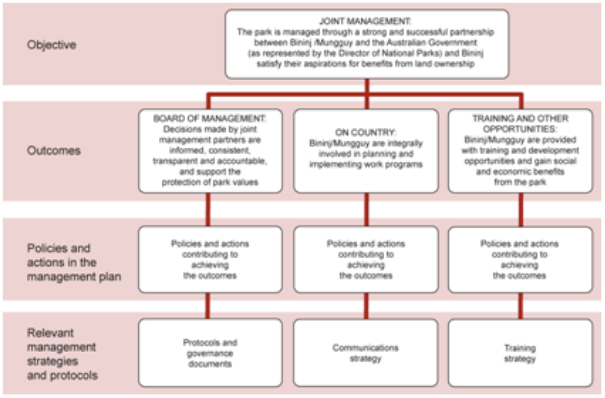

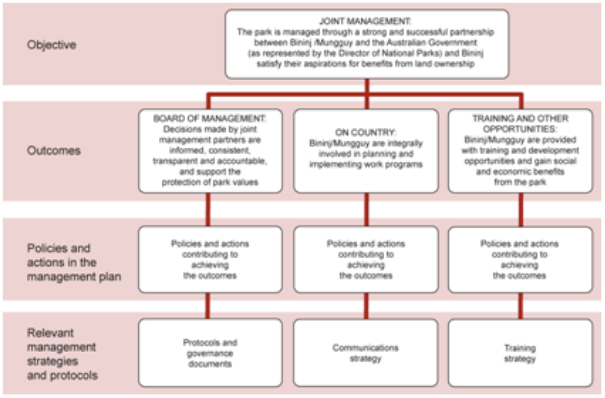

Figure 6: Line of sight for Section 4: Joint management 29

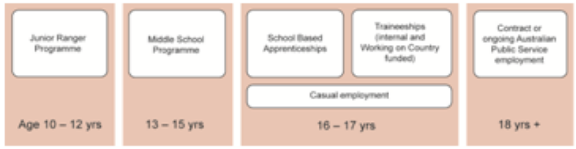

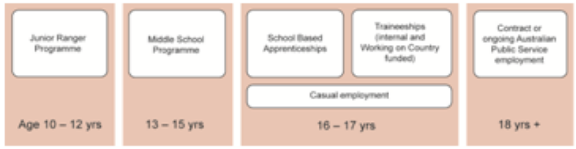

Figure 7: Summary of programmes supporting Indigenous employment

pathways in Kakadu 38

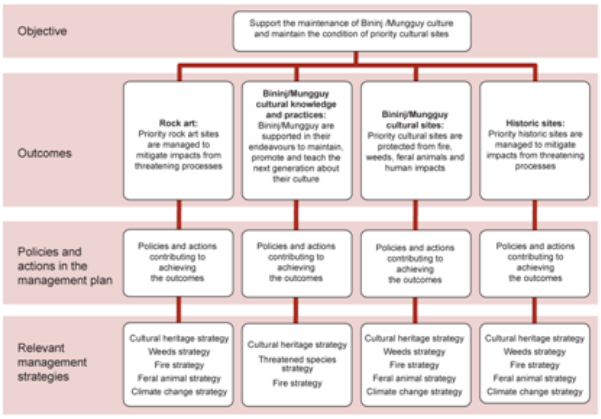

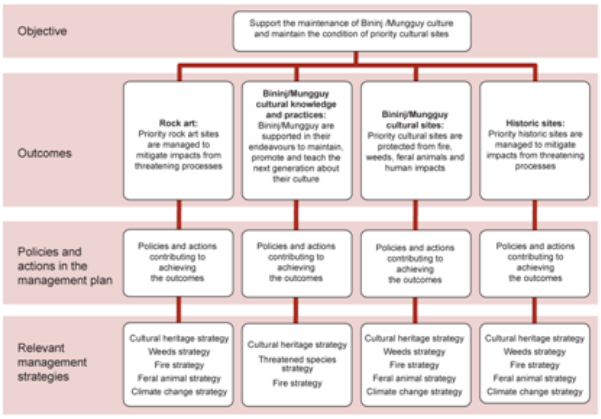

Figure 8: Line of sight for Section 5.1: Looking after culture 42

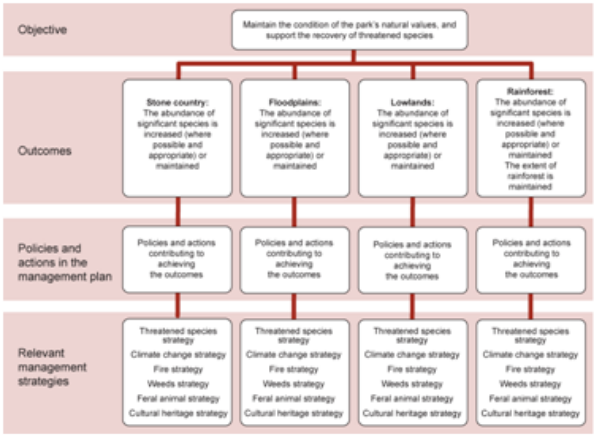

Figure 9: Line of sight for Section 5.2: Looking after country 58

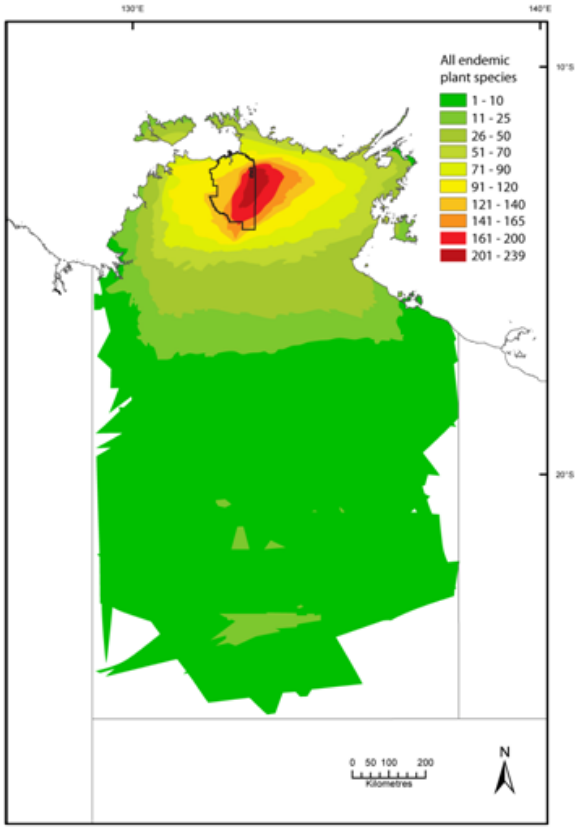

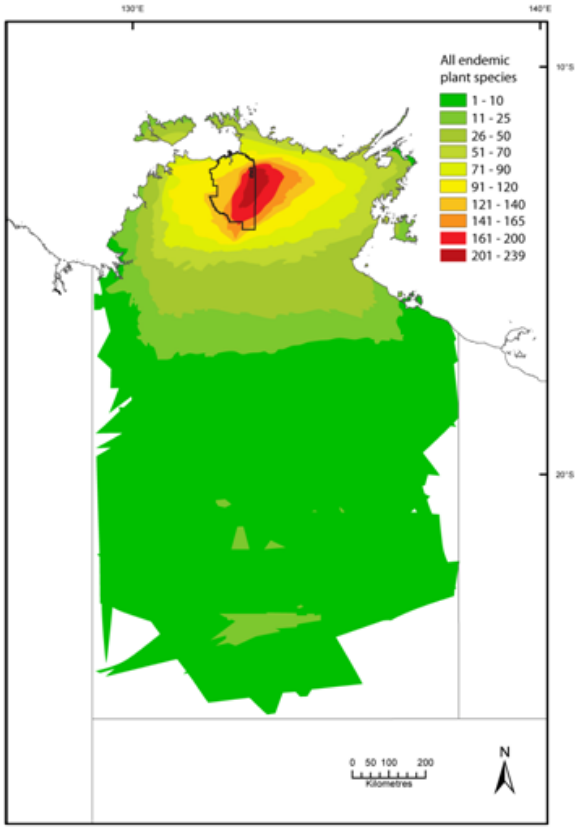

Figure 10: Endemic plants in the Northern Territory 61

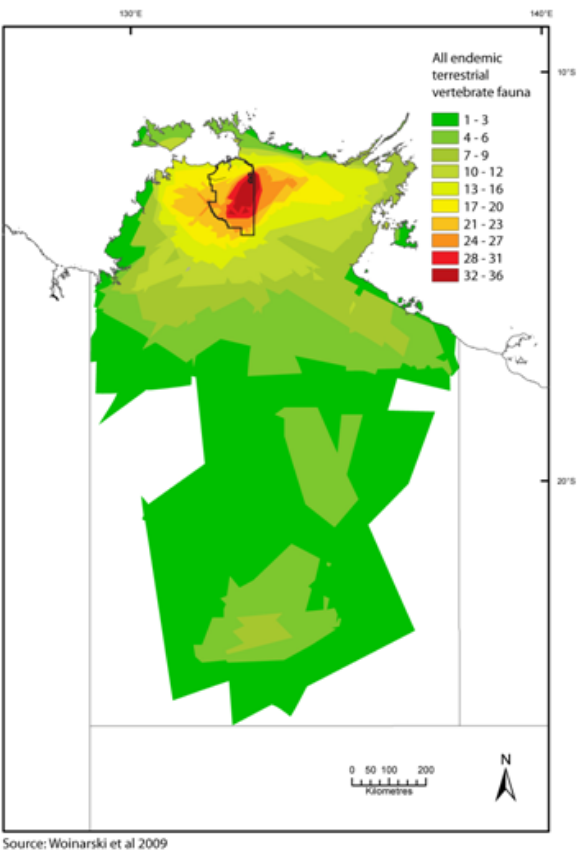

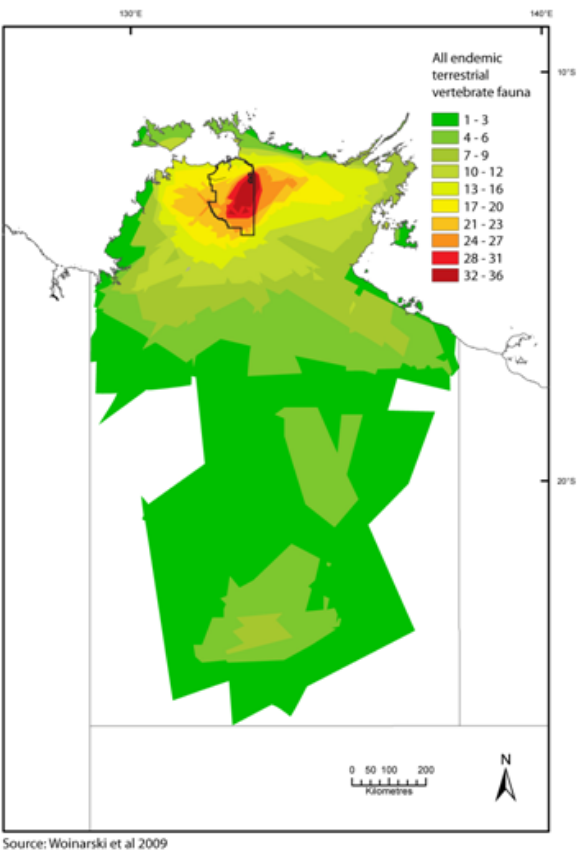

Figure 11: Endemic vertebrates in the Northern Territory 62

Figure 12: Line of sight for Section 5.3: Managing park-wide threats affecting values 77

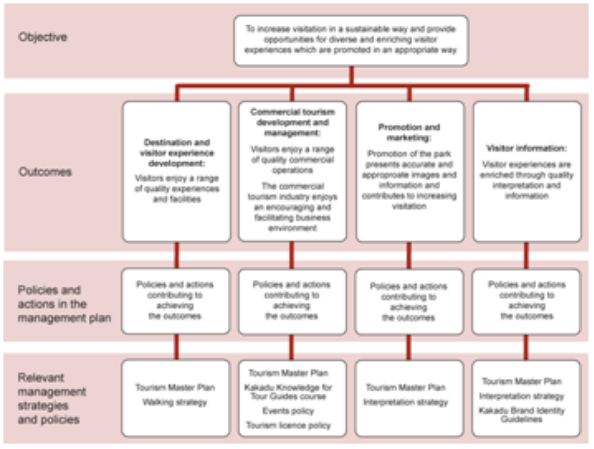

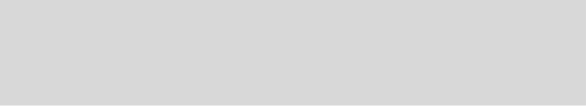

Figure 13: Line of sight for Section 6: Kakadu as a visitor experience 100

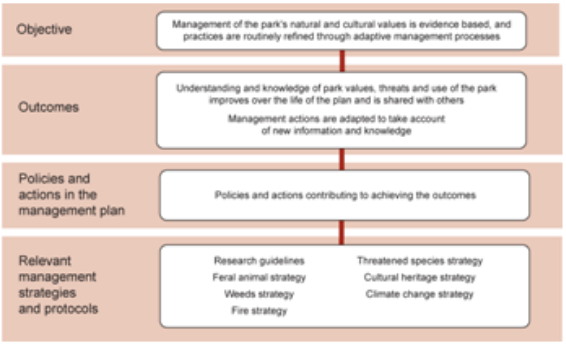

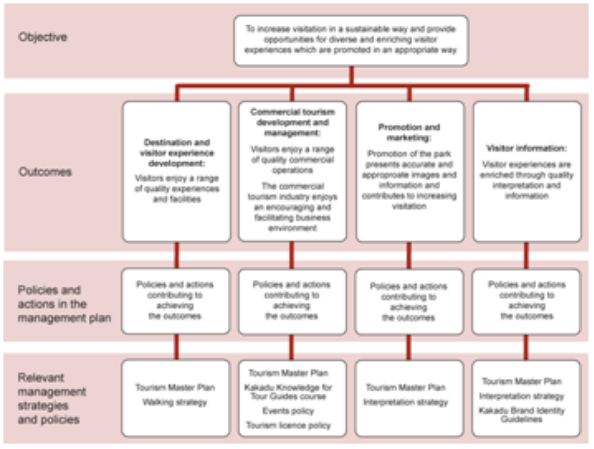

Figure 14: Line of sight for Section 7: Research and knowledge management 114

Figure 15: Parks Australia’s Management Effectiveness Framework 147

Figure 16: Camping areas in Kakadu 172

PART A

Introduction

Introduction

Kakadu National Park covers an area of 19,810 square kilometres within the Alligator Rivers Region of the Northern Territory of Australia. It extends from the coast in the north to the southern hills and basins 150 kilometres to the south, and 120 kilometres from the Arnhem Land sandstone plateau in the east, through wooded lowlands to the western boundary (Figure 1).

Kakadu is a cultural landscape that displays evidence of cultural practices dating back thousands of years and, in many cases, continue to be observed by Bininj/Mungguy in the park today. The park is diverse in language and tradition as it is home to many Aboriginal clan groups. Each clan group has responsibility for looking after and speaking for their own area of country. This responsibility is passed down through generations, along with the knowledge necessary to understand, manage and respect the ancient land. Use and management of the land by past and present generations of Bininj/Mungguy has helped to shape the landscape that we see today.

The park’s natural environment is a vast one of exceptional beauty and unique biodiversity. The rugged and ancient stone country provides refuge for a great diversity of native species, and is a hotspot of endemic plants and animals. Extensive floodplains support diverse habitats and a great concentration of waterbirds and other aquatic species. Largely intact woodlands and open forest dominate the lowlands and represent the largest area of savanna within a protected area in the world, while pockets of rainforest provide a cool and shady refuge for many other species.

Both the natural and cultural heritage values of the park have been recognised by its inscription on the World Heritage List under the World Heritage Convention. The park is also listed on the National Heritage List under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), and as a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar Convention. Many species that occur in the park are protected under international agreements including the Bonn Convention for conserving migratory species and Australia’s migratory bird protection agreements with China (CAMBA), Japan (JAMBA) and the Republic of Korea (ROKAMBA).

Creation

Every culture has a creation story. Aboriginal people believe that they have been here from the time of the first ancestors, or Nayuhyunggi (in the Gundjeihmi language), when landscapes formed, ancestral beings transformed themselves into animals and sacred places were created.

The Nayuhyunggi were the first people who formed the landscape, planted foods and left people and language behind. At the completion of their creative activities, they ‘sat down’ and left their essence in the landscape. The whole landscape is evidence of not only their past activities but also their current presence (Chaloupka 1993).

Figure 1: Location of Kakadu National Park

Figure 1: Location of Kakadu National Park

Creation Ancestors came in many forms. The Rainbow Snake (Almudj/Alyod in Gundjeihmi and Bolung in Jawoyn) is a spiritual being of great significance in Aboriginal culture in Kakadu. Other ancestral beings include Bula (important creator), Namarrgon (Lightning Man) and Warramurrungundji (Earth Mother). The landscape and its features were left by the Creation Ancestors. They instituted and created ceremonies, rules to live by, laws, plants, animals and people, then they turned into djang (dreaming places and their spiritual essence). They taught Aboriginal people how to live with the land, and from then on Aboriginal people became keepers of their country.

‘We Aboriginal people have obligations to care for our country, to look after djang, to communicate with our ancestors when on country and to teach all of this to the next generations.’

Combined statement from the Aboriginal members of the

Kakadu National Park Board of Management

Kinship

Every aspect of life and the responsibilities for looking after country is governed by kinship ties. Aboriginal languages have special linguistic features that eloquently express these ties and responsibilities.

Aboriginal society is organised into many kinds of social divisions. All people, plants, animals, places, weather, landscapes and ceremonies are divided into halves or moieties: the patrilineal moieties Duwa and Yirridjdja, and the matrilineal moieties Mardku and Ngarradjku.

Each moiety is subdivided into four pairs of subsections or ‘skin groups’, and a child’s skin group is determined by that of their mother. Skin groups are used in regulating marriages and addressing or referring to Aboriginal people in culturally appropriate ways.

Each clan and moiety has a number of clan totems and emblems. Sacred sites and other special places on each clan estate are the focus of religious life. If the totem is a plant or animal that is relied upon as a food source, then members of the owning clan traditionally had responsibilities to ensure a plentiful supply.

Clan estates and traditional owners

Kakadu includes the traditional lands of a number of Aboriginal clan groups.

‘Land and people go together. Every place has a clan name, and every place has a clan.’

Jacob Nayinggul, Manilikar clan

In English the term ‘traditional owner’ is commonly used to refer to someone who is a member of the clan associated with a particular clan estate. The term has a particular meaning under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Land Rights Act). In the Kakadu area primary responsibility to land is determined according to traditional Aboriginal law and custom and involves making important decisions about the management of country such as protecting resources and sacred sites. While a person belongs to the clan of their father they still have responsibilities to their mother’s clan estate. Both men and women may be acknowledged as senior traditional Aboriginal owners.

‘These laws need to be explained to non-Aboriginal people in the same way it is taught to children so we can all hold on to it and teach it to children who will grow up learning about their land with this law.’

Jacob Nayinggul, Manilikar clan

Language and language groups

Creation Ancestors were also responsible for the various languages that exist in the Park. These languages are associated with different tracts of land and the people who are the traditional owners. The traditional countries of some language groups are large and divided into distinct estates, others are smaller.

Making decisions about country

Bininj/Mungguy who have cultural responsibilities for management of a clan estate are key people in the planning and management of the park. Everyone who lives, works in or visits Kakadu must respect Bininj/Mungguy rules and it is important that these rules are passed on to young Bininj/Mungguy.

‘When I want to do something on country I have to ask the right person. To go and burn country or do weed control I have to ask the right person, traditional way, because there’s many important sites there or whatever. This is our way.’

Bessie Coleman, Wurrkbarbar clan

Background

Kakadu National Park (Figure 2) was established at a time when the Australian community was becoming more interested in the declaration of national parks for conservation and in recognising the land interests of Aboriginal people. A national park in the Alligator Rivers Region was first proposed in1965. Over the next decade several proposals for a major national park in the region were put forward by interested groups and organisations. One of these proposals suggested the name ‘Kakadu’, after the Gagudju people, for the national park. ‘Kakadu’ was the original spelling of the word as given by the biologist and anthropologist W Baldwin Spencer in 1912.

In 1973, the Australian Government set up a commission of inquiry into Aboriginal land rights in the Northern Territory. This commission considered how to recognise Aboriginal people’s land interests while providing for conservation management of the land. The commissioner in charge of this inquiry, Mr Justice Woodward, concluded: ‘It may be that a scheme of Aboriginal title, combined with national park status and joint management would prove acceptable to all interests’ (Woodward 1973).

In the early 1970s, significant uranium deposits were discovered in the Alligator Rivers Region at Ranger, Jabiluka and Koongarra. A formal proposal to develop the Ranger deposit was submitted to the Australian Government in 1975. The Government established the Ranger Uranium Environmental Inquiry to investigate the proposal, focusing on environmental issues and the social impact on Aboriginal people.

During the time the inquiry was held, the Land Rights Act was passed by the Commonwealth Parliament. The Act allowed the commission set up to conduct the Ranger Inquiry to determine the merits of a claim to traditional Aboriginal ownership of land in the Alligator Rivers Region. This was the first claim heard under the Land Rights Act.

Figure 2: Kakadu National Park

The Ranger Inquiry tried to work out a compromise between the problems of conflicting and competing land uses, including Aboriginal people living on the land, establishing a national park, uranium mining, tourism and pastoral activities in the Alligator Rivers Region. In August 1977, the Australian Government responded to the recommendations of the Ranger Inquiry. It accepted almost all the recommendations including those about granting Aboriginal title to areas in the Alligator Rivers Region and establishing Kakadu National Park in stages.

An arrangement was made for the traditional owners to lease land granted to them to the Australian Government for management as a national park. Mining would not be permitted in the park but was provided for on areas excluded from the park.

Establishment of the park and the park as Aboriginal land

Kakadu National Park was declared under the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1975 (NPWC Act) in three stages between 1979 and 1991. The NPWC Act was replaced by the EPBC Act in 2000. The park continues as a Commonwealth reserve under the EPBC Act pursuant to the Environmental Reform (Consequential Provisions) Act 1999, which deems the park to have been declared for the following purposes:

- the preservation of the area in its natural condition

- the encouragement and regulation of the appropriate use, appreciation and enjoyment of the area by the public.

Each stage of the park includes Aboriginal land under the Land Rights Act that is leased to the Director of National Parks (the Director), or land that is subject to a claim to traditional ownership under the Land Rights Act (see Figure 3).

Most of the land that was to become part of Stage One of Kakadu National Park was granted to the Kakadu Aboriginal Land Trust under the Land Rights Act in August 1978 and, in November 1978, the Land Trust and the Director signed a lease agreement for the land to be managed as a national park. Stage One of the park – covering the leased land and land required for the township of Jabiru and some adjoining areas – was declared on 5 April 1979.

Stage Two was declared on 28 February 1984, originally as Kakadu (Stage 2) National Park and later incorporated into Kakadu National Park on 20 December 1985. In March 1978, a land claim was lodged under the Land Rights Act for the land included in Stage Two of Kakadu. The land claim was partly successful and, in 1986, three areas in the eastern part of Stage Two were granted to the Jabiluka Aboriginal Land Trust. A lease between the Land Trust and the Director of National Parks was signed in March 1991. At the time of preparing this plan the rest of Stage Two (except the commercial lease near the South Alligator River) is subject to ‘repeat’ land claims under the Land Rights Act. The land may become Aboriginal land during the life of this plan and will be leased to the Director.

In June 1987, a land claim was lodged for the land in the former Goodparla and Gimbat pastoral leases that were to be included in Stage Three of Kakadu. The other areas to be included in Stage Three – the area known as the Gimbat Resumption and the Waterfall Creek Reserve (formerly known as UDP Falls, UDP standing for Uranium Development Project) – were later added to this land claim. Stage Three of Kakadu National Park was declared progressively on 12 June 1987, 22 November 1989 and 24 June 1991.

Figure 3: Aboriginal land and land claims in Kakadu National Park

as at April 2014

The progressive declaration resulted from the debate over whether mining should be allowed at Guratba (Coronation Hill), which is located in the middle of the culturally significant area referred to as the Sickness Country. The traditional owners’ wishes were ultimately respected and the Australian Government decided that there would be no mining at Guratba. In 1996 the land in Stage Three, apart from the former Goodparla pastoral lease, was granted to the Gunlom Aboriginal Land Trust and leased to the Director of National Parks to continue being managed as part of Kakadu National Park. At the time of preparing this plan the land claim to the Goodparla area is still ongoing. The land may become Aboriginal land during the life of this plan and will be leased to the Director.

In 1997 the High Court found the Proclamation for Stage Three of Kakadu was invalid in relation to a number of mining leases including Coronation Hill and El Sherana. Following negotiation of a settlement with the holder of the Stage Three mining leases (Newcrest Operations Ltd), all affected areas were eventually incorporated into the park by a proclamation under the EPBC Act in May 2007.

In 1997 the Mirarr people, acknowledged as the traditional owners of the Jabiru township land, made a native title claim under the Native Title Act 1993 to the township area and two adjoining areas of the park. Agreement to settle the claim was reached in 2009. Under the agreement the claim areas would be granted as Aboriginal land under the Land Rights Act. At the time of preparing this plan the settlement has been partially implemented by the granting of the two areas adjoining the town to the Kakadu Aboriginal Land Trust and leased-back to the Director. The claim over the town area should be resolved during the life of this plan.

The Koongarra Project Area, which had been excluded from the declaration of Stage One of Kakadu in 1979, was incorporated into the park by a proclamation under the EPBC Act in February 2013.

As well as being important to Bininj/Mungguy, many things about Kakadu are special and important to other people. However, there are some attributes of the park which are fundamental to the park’s purpose and significance. These cultural and natural (or country) values are summarised in the park values statement and reflect aspects of the park that are recognised through World Heritage, Commonwealth Heritage and Ramsar listings.

This values statement (Table 1) identifies and separates the cultural and country values of the park because each have distinct threats and management priorities. Identification and separation of the cultural and country values assists in planning and management for them.

For Bininj/Mungguy, there are no local language words that equate exactly with the Western concepts of ‘culture’ and ‘country’. For Bininj/Mungguy the word ‘country’ not only refers to the landscape but also captures the rich interconnections between land and people – they are inseparable. Professor of Anthropology, Deborah Bird Rose, describes this concept in the following way:

‘Indigenous people talk about country in the same way they talk about a person; they speak to country, sing to country, visit country, worry about country, feel sorry for country, and long for country. People say that country knows, hears, smells, takes notice, takes care, is sorry or happy .... country is a living entity with a yesterday, today and tomorrow, with a consciousness and a will toward life.’ (Rose 1996)

Identification and recognition of the park’s values ensures a shared understanding about what is most important about the reserve, and the value statement helps to focus management and planning on the important aspects. If the values are allowed to decline the park’s purpose and significance would be jeopardised.

The foundation for managing these values and the related threats and management issues includes the protection provided by the EPBC Act. Under the EPBC Act the park is assigned an Australian International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) category (national park) in this management plan, and the park must be managed in accordance with the management principles relevant to the assigned category and the obligations prescribed in the EPBC Regulations, and with regard to World Heritage, National Heritage and Ramsar listings.

Table 1: Kakadu National Park Values Statement

|

Kakadu National Park – Values Statement Background Kakadu National Park is Aboriginal land located in the Top End of Australia’s Northern Territory. It has been home to Indigenous people for more than 50,000 years. The people of this country, Bininj in the north and Mungguy in the south, have always cared for the land. Kakadu is an ancient landscape of exceptional beauty and unique biodiversity. It stretches almost 20,000 square kilometres and is located at the convergence of four distinct bioregions: the Arnhem Plateau, Arnhem Coast, Darwin Coast and Pine Creek bioregions. Kakadu includes mangrove-fringed tidal plains in the north, vast floodplains, lowlands and the sandstone cliffs of the Arnhem Land escarpment. These landscapes undergo spectacular changes throughout the year with the passing of each of the six seasons of Kakadu. The park is home to a remarkable variety and concentration of wildlife, and many plants and animals are threatened or found nowhere else in the world. The park was proclaimed under the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1975 in three stages between 1979 and 1991 for the purposes of: - the preservation of the area in its natural condition

- the encouragement and regulation of the appropriate use, appreciation and enjoyment of the area by the public.

The park is first and foremost home to Bininj/Mungguy. The long and continuing history of Bininj/Mungguy custodianship of Kakadu is one of the most important things about the park. Bininj/Mungguy have leased their land to the Australian Government to be jointly managed as a national park to protect and manage its priceless natural and cultural heritage. The management of the park is subject to a number of competing value systems, with Bininj/Mungguy and park staff working hard through joint management to balance the protection of Bininj/Mungguy culture and the park’s natural values with the needs of park visitors and other stakeholders. |

International listings |

Kakadu National Park was first inscribed on the World Heritage list in 1981 and was subsequently expanded and re-inscribed in 1987 and again in 1992. The Koongarra area was added to the World Heritage Area in June 2011. The park meets five criteria of outstanding universal values as set out in the World Heritage Convention. The park meets all nine criteria for identifying wetlands of international importance under the Ramsar Convention. Numerous migratory species that occur in Kakadu are protected under international agreements such as the Bonn convention for conserving migratory species, and Australia’s migratory bird protection agreements with China (CAMBA), Japan (JAMBA) and the Republic of Korea (ROKAMBA). |

Values |

This values statement identifies and separates the cultural and country values of the park. However, it must be remembered that for Bininj/Mungguy the word ‘country’ not only refers to the landscape but also captures the rich interconnections between land and people – they are inseparable and there are no Bininj/Mungguy words that equate exactly with the Western concepts of ‘culture’ and ‘country’. |

Cultural valuesThe park is an internationally significant cultural landscape inscribed with the signs of an ancient and continuing Bininj/Mungguy presence. ‘Bininj culture really strong ... very strong for us Bininj. When I was a girl my grandmother, I learn. Same thing I do with younger generation. You have to look after country, for your grandfather country, like mother country, take care.’ Yvonne Margarula, Mirarr/Gundjeihmi clan - Stone country in the park protects one of the world’s greatest concentrations of rock art sites, estimated to range in age from more than 20,000 years to the recent present, and constituting one of the longest historical records of any group of people in the world.

- The park is a home for Bininj/Mungguy. It represents the oldest culture in the world with continuous occupation over 50,000 years, and is a place where Bininj/Mungguy have the opportunity to live and maintain their culture and pass it on to future generations.

- The park protects a rich collection of Bininj/Mungguy cultural sites, including sacred and ceremonial sites, and archaeological sites that are some of the oldest occupation sites in Australia.

- The park includes a collection of historic sites that tell the important story of the park‘s recent history and represent a way of life and use of country that no longer exist.

|

Values - continued |

Country valuesThe park is an internationally significant natural landscape (including landforms and biota of great antiquity) comprising outstanding representation of interconnected ecosystems whose extent, intactness and integrity provides for a distinctive and rich biodiversity including viable populations of threatened, endemic and culturally significant species. ‘The park is one big living space ... the stone country is where everything comes from and is connected to the floodplains. It is important for the bush tucker, breeding, but everything is equally important as Kakadu is a living space.’ Jeffrey Lee, Djok clan The park is a vast and continuous natural environment that comprises four main landscape types, each with distinct natural and cultural values: - The rugged, ancient and spectacular stone country within the park comprises a great diversity of native species, including many threatened species, and at least 160 plant species and many animals that occur nowhere else in the world.

- The freshwater and saltwater country within the park encompasses some of the largest and most diverse river systems in northern Australia, including extensive wetlands, floodplains and mangroves that support vast numbers of waterbirds and other aquatic and marine species.

- The vast, largely intact and dominant lowland woodlands and open forest in the park represents the largest area of savanna within a protected area in the world and provides habitat for the majority of the park’s plants and animals.

- The rainforest areas within the park contribute a rich set of very different plant and animal species to those otherwise found in the park, including restricted, threatened and culturally significant species.

|

As a result of these values, the park has great economic, social, research and regional significance. |

How Kakadu is significant locally

To Bininj/Mungguy, Kakadu is of particular importance as it is their home and they have important cultural obligations to look after country. Many Bininj/Mungguy consider that they cannot or should not move to other places to live or work. The park is their traditional homeland and it is important to them that they are able to look after their country and culture and make sure that visitors to their country are safe. Many other people also enjoy the benefits that come from living in the park. For many residents in Jabiru and the Kakadu region, Kakadu is not only a place to live and work but also a place for recreation and a place where they can appreciate and learn about the park’s natural and cultural heritage.

How Kakadu is significant regionally

Conservation

The park is both representative and unique. It is representative of the ecosystems of a vast area of northern Australia. It is unique because it incorporates a large drainage basin (the South Alligator River) in its near entirety and all of the major habitat types of the Top End. It is where the Arnhem Land Plateau meets the southern hills and basins and the Alligator Rivers coastal floodplains (see Figure 4).

The stone country in Kakadu is part of the plateau of western Arnhem Land, which is the most significant region in the Northern Territory for biodiversity. It contains the greatest number of endemic and threatened species in the Northern Territory and also supports a high proportion of the Northern Territory’s rainforest estate. Kakadu is important for conservation in the region because it is a large area managed as a national park, whereas other areas of Top End habitats are managed primarily for purposes such as pastoralism, mining, or defence force use.

Most of Kakadu is included within two Northern Territory Sites of Conservation Significance, the Western Arnhem Plateau and the Alligator Rivers coastal floodplain, due to the occurrence of large numbers of threatened and endemic species and large aggregations of waterbirds.

Regional economy

Tourism is very important to the regional economy, particularly in terms of employment. For the financial year 2013–14, Tourism NT reported that the direct value of tourism to the Northern Territory was $790 million (Tourism NT 2014a) and in the year ending March 2015 the Northern Territory attracted 1.34 million visitors (Tourism NT 2015a). It is estimated that in 2013–14 Kakadu National Park attracted 190,400 visitors. In addition to its significant contribution via the tourism market, the park purchases significant quantities of goods and services from regional suppliers.

It is important to the Northern Territory Government, Bininj/Mungguy and park management that tourism development in the park complements the tourism marketing strategies and plans for regional tourism development. The park is a significant provider of direct and indirect employment in the regional economy and provides opportunities for Bininj/Mungguy people and organisations through direct employment and outsourcing of services.

Recreation

Many people from Darwin, Katherine and Pine Creek use the park for recreation. Fishing, camping, bushwalking and visiting with relatives and friends are some of the most popular activities. Kakadu offers recreational opportunities that complement those offered in the other parks, reserves and attractions in the region, such as the Mary River National Park, Nitmiluk, Litchfield and Gurig national parks, Fogg Dam, Window on the Wetlands and the Territory Wildlife Park.

Figure 4: Kakadu’s major landscapes

How Kakadu is significant nationally

Conservation

Nearly 1,600 plant species have been recorded in Kakadu, including 15 species considered threatened. More than one-third of Australia’s bird fauna (271 species) and about one-quarter of Australia’s land mammals (77 species) are found in the park, along with 132 species of reptiles and 27 species of frogs. The region is the most species-rich in freshwater fish in Australia, and over 246 species of fish have been recorded in tidal and freshwater areas within the park. Additional species new to western science have also been discovered in the park since its inscription, most recently a gudgeon and a goby fish in 2013.

Kakadu is one of 19 World Heritage places in Australia and is included on the National Heritage List under the EPBC Act. At the time of preparing this plan, Kakadu is on the list of indicative places under consideration for inscription on the Commonwealth Heritage List.

The national park status and effective conservation management of Kakadu contribute significantly to meeting the objectives of a number of Australian national conservation strategies including the National Strategy for the Conservation of Australia’s Biological Diversity; the National Strategy for Ecologically Sustainable Development; and the National Forest Policy. The park also plays a major role in protecting representative examples of ecosystems within the Arnhem Plateau and Pine Creek bioregions, and contributing to the National Reserve System’s network of protected areas across Australia.

National economy

Tourism is a significant contributor to the Australian economy providing for $43 billion or 2.7 per cent of the national gross domestic product in 2013-14 (Tourism Research Australia 2014) and is actively encouraged and promoted nationally and internationally by government agencies and tourism industry stakeholders. Along with other places of natural beauty and cultural significance in Australia, such as Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park and the Great Barrier Reef, Kakadu is a major tourism attraction for domestic and overseas visitors.

Joint management

The management arrangements in the park between Bininj/Mungguy and the Director of National Parks continue to be cited as an example of an innovative cooperative management arrangement. Protected area and land management authorities and groups of Indigenous people interested in joint management from within Australia and overseas regularly visit the park, and the model of joint management used in Kakadu and Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Parks has been a blueprint for joint management more broadly.

How Kakadu is significant internationally

Kakadu is inscribed on the World Heritage List under the World Heritage Convention for its outstanding natural and cultural values. These values are described in the Retrospective Statement of Outstanding Universal Value (UNESCO 2014). Stage One of the park was inscribed on the list in 1981 and Stage Two in 1987. The whole of the park was listed in December 1992. In recognition of its outstanding natural and cultural values, the Koongarra area was added to the Kakadu World Heritage Area by the World Heritage Committee on 27 June 2011. As of 2013 Kakadu was one of only 29 World Heritage sites listed internationally for both natural and cultural heritage.

Appendix A: summarises the World Heritage criteria and attributes of Kakadu.

As a listed World Heritage site Kakadu is recognised internationally for its rock art and archaeological sites which record a living cultural tradition that continues today.

The archaeological sites and rock art sites within the park exhibit great diversity, both in space and through time, yet embody a continuous cultural development. These sites are recognised internationally as preserving a record, not only in the form of archaeological sites but also through rock art, of human responses and adaptation to major environmental change including rising sea levels. Kakadu also contains archaeological sites which are currently some of the oldest dated within Australia.

Kakadu is also listed as a Wetland of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention. The park was previously listed as two separate Ramsar sites. These were Stage One, listed on 12 June 1980 and extended in 1995; and Stage Two, listed on 15 September 1989. On 28 April 2010 the two Ramsar sites were combined to form a single Ramsar site encompassing the entire park. Appendix B summarises the Ramsar criteria of the park.

In March 1996, the parties to the Ramsar Convention agreed to establish an East Asian–Australasian Flyway to protect areas used by migratory shorebirds. The flyway provides for an East Asian–Australasian shorebird reserve network of sites that are critically important to migratory shorebirds. The wetlands of Kakadu are part of this reserve network.

Numerous migratory species that occur in the park are protected under international agreements which include the Bonn Convention for conserving migratory species, and Australia’s migratory bird protection agreements with China (CAMBA), Japan (JAMBA) and the Republic of Korea (ROKAMBA) (Appendix C). Forty of the species listed under the Bonn Convention are found in Kakadu, as are 51 of the birds listed under CAMBA and 46 of the birds listed under JAMBA. Appendix D provides the EPBC Act listed migratory species that occur in the park.

The park encompasses all or most of three contiguous internationally recognised Important Bird Areas (Arnhem Plateau, Kakadu savanna and Alligator Rivers floodplain) substantially due to the presence of large numbers of globally threatened bird species.

Joint management is a partnership between Bininj/Mungguy and government to share the land in Kakadu, and share responsibility for managing the land. Through joint management the partners work to protect the park’s values and share it with the public, bringing together traditional knowledge and modern science, and creating opportunities for Bininj/Mungguy to be involved in park management at all levels, establish businesses and preserve their culture for future generations.

The lease of Aboriginal land associated with the declaration of Stage One of Kakadu National Park in 1979 set out terms for consultation with traditional owners. At the same time the government committed to manage all of the land in the park as if it were Aboriginal land.

This effectively commenced joint management of the park and joint management of protected areas in Australia. Kakadu was also one of the first formally co-managed protected area arrangements in the world (Zurba et al. 2012). Since the commencement of joint management, the relationship between the Director of National Parks and Bininj/Mungguy has matured and evolved to the joint management relationship it is today.

Joint management in Kakadu is formally based on a legal framework set in place by the NPWC Act (continued under the EPBC Act) and the Land Rights Act. The Land Rights Act provides for the granting of land to Aboriginal Land Trusts for the benefit of relevant Aboriginals (the traditional Aboriginal owners and other Aboriginals with rights of use and occupation) and requires land granted in the Alligator Rivers Region to be leased to the Director of National Parks. The EPBC Act provides for the park to be managed by the Director in conjunction with Bininj/Mungguy through the Board of Management. The Director is assisted by Parks Australia, whose staff are employees of the Department of the Environment assigned to the Director (see also Section 9.10: Implementing and evaluating the plan).

This is the sixth management plan for Kakadu National Park. The fifth plan came into operation on 1 January 2007 and ceased to have effect on 31 December 2013.

Section 366 of the EPBC Act requires that the Director of National Parks and the Board of Management for a Commonwealth reserve prepare management plans for the reserve. In addition to seeking comments from members of the public, the relevant land council and the relevant state or territory government, the Director and the Board of Management are required to take into account the interests of the traditional owners of land in the reserve and of any other Indigenous persons interested in the reserve.

Prior to preparing this plan an audit (DNP 2012) was conducted to review the implementation of the fifth plan and to provide recommendations to assist with the preparation of this plan. For that purpose, nine independent auditors were engaged based on their expertise relevant to different sections of the plan. The auditors were asked to investigate whether the actions and policies in the plan were implemented and whether they successfully met the aims of each section of the plan.

The audit’s findings suggest that some aspects of park management could be improved, including:

- monitoring and reporting to provide evidence-based measures of progress

- monitoring and treatment of invasive plants and animals

- addressing threatened species decline

- supporting and improving consultation with Bininj/Mungguy

- assisting with proposals for establishing new living areas within the park

- improving opportunities for:

- direct employment of Bininj/Mungguy

- Bininj/Mungguy contracts for park maintenance activities.

The auditors also suggested that there should be a clearer link (or line of sight) between the park’s management actions and the desired outcomes and objectives, and that the performance indicators should be able to clearly demonstrate if management of the park is achieving the desired outcomes and objectives.

In February 2012 a notice was published inviting the public and relevant stakeholders to have their say towards the development of this plan. Seven formal submissions were received and the views expressed in those submissions were considered in the development of this plan.

The Kakadu National Park Board of Management (the Board) resolved that consultations be undertaken with Bininj/Mungguy on a clan-by-clan basis to seek comments on issues related to the management of the park. During the drafting stage of this plan, park staff conducted extensive consultations with over 128 Bininj/Mungguy during 14 participatory planning meetings. These meetings covered a range of park management issues including decision-making procedures; natural and cultural resource management; visitor management and park use; and Bininj/Mungguy employment. A number of Board meetings were also conducted to consider the development of the draft management plan and comments made by stakeholders. Appendix E summarises the consultations and planning timeframes undertaken in developing this plan.

Other stakeholder groups and individuals who were consulted during the preparation of this management plan include:

- Kakadu Tourism Consultative Committee (KTCC) members

- Kakadu Research and Management Advisory Committee (KRMAC) members

- external natural and cultural resource management experts including Dr John Woirnaski,

Dr Sandy Blair and Dr Sally May - Northern Land Council and local Aboriginal associations and corporations

- neighbours and residents including the Nitmiluk National Park Board of Management and Energy Resources Australia

- Amateur Fisherman’s Association of the Northern Territory and Tourism NT

- park staff.

On 3 December 2014 a draft version of this plan was released and a notice was published seeking comments from the public, relevant stakeholders and anyone with an interest in the park. The public comment period closed on 14 February 2015 and a total of 31 submissions were received. The comments contained in these submissions were considered when finalising this plan.

The framework of this plan is structured around two discrete elements

Part C. Managing Kakadu: actions the Director can and will do over the life of this plan.

- This part of the plan is structured around joint management, protecting the cultural and natural values of the park, developing and promoting Kakadu as a visitor destination, and increasing our understanding of the park’s values. It sets out policies which will apply to the Director’s activities over the life of the plan as well as describing the actions that will be taken towards achieving the outcomes described in the plan. Any policies relating to provisions of the EPBC Regulations that specifically apply to the activities of the Director in managing the park are also described.

Part D. Managing use of Kakadu: what park users need to understand about accessing the park.

- This part of the plan is structured around how the Director will enable and manage appropriate visitor and stakeholder activities in the park in accordance with the EPBC Act and EPBC Regulations. It sets out any policies which apply to park users. Policies include those related to provisions in the EPBC Regulations as well as policies which more broadly protect the park values or contribute to the effective management of the park.

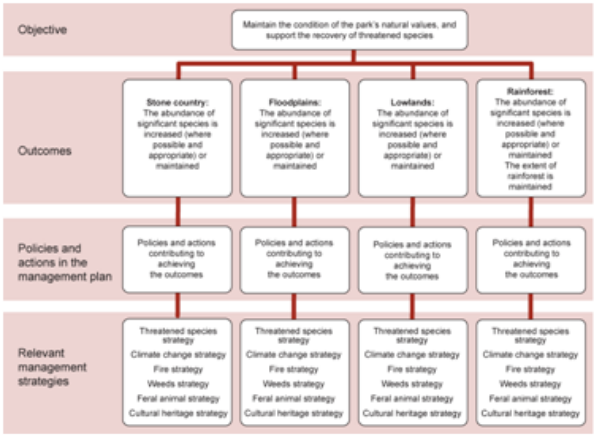

A values-based approach to planning

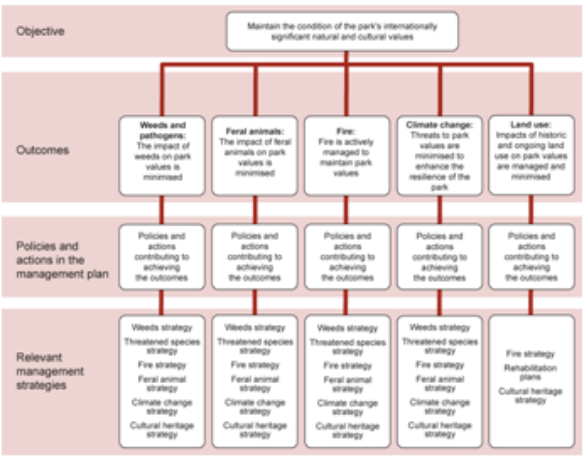

The essential natural and cultural values of the park identified in Table 1 clearly define what management of the park seeks to protect and present. Planning in the park and the structure of this management plan are based around these values so that the links (or line of sight) between the values, the desirable outcomes and objectives, the management actions and policies, and the performance indicators are visible and understood. Figure 5 illustrates this line-of-sight and simplified line-of-sight diagrams are used throughout this management plan.

Prioritisation

Section 5 of this plan (Looking after culture and country) is about managing the park values and identifies the existing and potential threats to the values. A number of the threats to the values were identified by a range of experts as being of high significance and are the basis for developing management actions to protect the values.

In addition to management focusing on significant threats, priority areas reflecting country values, priority cultural sites and significant species (see Table 2) will also be identified

(see Section 7: Research and knowledge management). This acknowledges that in a resource-constrained environment, it may not be possible to manage threats to values across all landscapes or to actively manage all rock art or other cultural sites. Defining priority areas will form part of a broader approach to prioritising actions from the management plan (see Section 9.10: Implementing and evaluating the plan). For example, a site where a ‘highly significant’ threat overlaps a priority area is likely to be prioritised for action before other sites.

The performance monitoring plan (Section 9.10) will further describe which areas, sites, species and threats will be routinely monitored and the methods to be used for monitoring.

For other sections of the management plan – those relating to joint management, tourism, Jabiru and other living areas and business management – a series of management issues are presented rather than threats to values. These issues are not assessed for significance but actions are included to address them unless noted otherwise.

The park’s planning hierarchy

This management plan provides the strategic direction for managing the park over the next 10 years. It refers to management strategies, guidelines, plans and operational protocols that have been developed or will be developed with the explicit purpose of contributing to the achievement of objectives and outcomes described in this plan. These strategies, plans, guidelines and operational protocols will be reviewed and updated in accordance with this management plan and the Parks Australia Management Effectiveness Framework. Development of such documents is guided by relevant policies and actions in this plan; involves consultation with traditional owners, other relevant Aboriginals and other stakeholders; and is subject to final endorsement by the Board of Management. Strategies and guidelines for the implementation of management programmes for the park are often made available on the park website.

Figure 5: Conceptual framework for the structure of this plan

Table 2: Focus of management for the protection of park values

Values | Focus | Comments |

Cultural values | Priority sites | Identified sites with high cultural values that are a priority for management and/or monitoring |

Country/natural values | Priority areas | Identified areas within the major park landscapes with high natural values that are a priority for management and/or monitoring |

Country/natural values | Significant species | Species that are threatened, endemic, have cultural value or are of conservation concern for other reasons (declining, fire sensitive etc.) |

Country and cultural values | Significant threats | The threats to values in this plan that are described as ‘highly significant’ will have actions specifically tailored to address them within the same section of the plan. Actions for threats to values that are identified as being ‘moderately significant’ or of ‘low significance’ may be included in the same section of the plan or in Section 5.3: Managing

park-wide threats affecting values. |

PART B

General provisions

General provisions

and IUCN category

This management plan may be cited as the Kakadu National Park Management Plan 2016-2026.

This management plan will come into operation following approval by the Minister under s.370 of the EPBC Act, on a date specified by the Minister or the day after it is registered under the Legislative Instruments Act 2003, whichever is later, and will cease to have effect ten years after commencement, unless revoked sooner or replaced with a new plan.

Definitions of terms, concepts, legislation and acronyms used in this plan are provided in the glossary in Appendix F.

The EPBC Act requires this management plan assign the park to one of the seven Australian International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) categories. The Australian IUCN categories correspond to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) protected area categories. The EPBC Regulations (Schedule 8) prescribe the Australian IUCN management principles for each IUCN category. The Australian management principles for IUCN protected area category II require taking account of the needs and aspirations of traditional owners and other Indigenous people in the park, specifically:

- The needs of Indigenous people including subsistence resource use, to the extent that they do not conflict with the Australian IUCN management principles.

- The aspirations of traditional owners of land within the reserve or zone, their continuing land management practices, the protection and maintenance of cultural heritage and the benefit the traditional owners derive from enterprises, established in the reserve or zone, consistent with Australian IUCN management principles should be recognised and taken into account.

The category to which the park is assigned is guided by the purposes for which the park was declared (see Appendix G: Legislative context). The purposes for which Kakadu National Park was declared are consistent with the characteristics for IUCN protected area category II ‘national park’.

Under the IUCN categorisation system (Dudley 2008), it is acknowledged that the primary objective for a protected area should apply to at least three-quarters of the protected area–known as the 75 per cent rule. The IUCN thus recognises that up to 25 per cent of land or water within a protected area can be managed for other purposes so long as these are compatible with the primary objective of the protected area.

Within Kakadu it is estimated that less than one per cent of the park is utilised for residential and visitor accommodation, infrastructure and other uses. Use of the park for these purposes is clearly consistent with the IUCN guidelines for applying protected area management categories (Dudley 2008) and not inconsistent with the Australian IUCN management principles for the National Park category.

Policies

3.4.1 The park is assigned to IUCN protected area category II ‘national park’ and will be managed in accordance with the prescribed management principles in Schedule 8 of the EPBC Regulations for that category and listed in Appendix H (IUCN administrative and management principle schedules).

3.4.2 Any areas that may be added to the park during the life of the plan will be managed in accordance with the IUCN protected area category II management principles and relevant policies and actions in this plan.

PART C

Managing Kakadu

What the Director will do to:

work with Bininj/Mungguy

work with Bininj/Mungguy

support the aspirations of Bininj/Mungguy to be actively involved in decision-making and park management

support the aspirations of Bininj/Mungguy to be actively involved in decision-making and park management

protect and present the values of Kakadu

protect and present the values of Kakadu

ensure effective park management.

ensure effective park management.

This section sets out the policies for supporting joint management in Kakadu, including any EPBC Act provisions which directly relate to the Director of National Parks (the Director), and the actions the Director will take over the life of the plan to work towards achieving the objective and outcomes of this section.

Objective

The park is managed through a strong and successful partnership between Bininj/Mungguy and the Australian Government (as represented by the Director of National Parks), and Bininj/Mungguy satisfy their aspirations for benefits from land ownership

Joint management is about Bininj/Mungguy and Parks Australia working together and deciding what should be done to manage the park with and on behalf of Bininj/Mungguy and for other interests. The partners work together to solve problems, sharing decision-making responsibilities and exchanging knowledge, skills and information. An important objective of joint management is to ensure that Bininj/Mungguy traditional knowledge and skills associated with looking after culture and country, and cultural rules regarding how decisions are made, continue to be respected and maintained.

Overarching principles for joint management

This section of the plan provides the framework for effective joint management processes across all elements of this plan. In jointly managing the park the following overarching principles apply:

- Bininj/Mungguy cultural and traditional knowledge, customs, values and priorities will be respected and will inform management priorities and programmes

- Bininj/Mungguy will be encouraged and supported to guide and actively participate in the development, implementation and review of management programmes and all aspects of park management

- the land management skills and expertise of both joint management partners will be utilised to manage the park

- the joint management partners will share responsibility for decision-making and managing the park.

The joint management relationship in Kakadu has evolved since the lease agreement was signed for Stage One of the park in 1978. The elders who ‘foot walked’ the country and were intimately connected to the land have now passed on. The next generation of Bininj/Mungguy have grown up with the park joint management relationship and have stepped up as the decision makers. Some people have expressed concerns about the pace of change (both Bininj/Mungguy and Balanda changes) and the effects that these changes are having on people’s lives today. It is vitally important that Bininj/Mungguy continue to be involved in park management, and equally important that management of the park continues to actively negotiate a balance that ensures the values of the park are looked after, the aspirations of Bininj/Mungguy are met, and the interests of other stakeholders are accommodated as far as possible. The joint management relationship will continue to change and evolve over the life of this plan and into the future. Ongoing investment in training and other capacity building will help to nurture new leaders, and new opportunities, such as the outsourcing of park tasks, will continue to be identified and further developed.

Figure 6 illustrates the line of sight for this section of the plan.

Figure 6: Line of sight for Section 4: Joint management

Outcome

- Decisions made by the joint management partners are informed, consistent, transparent and accountable, and support the protection of park values

Performance indicators

- Board governance processes followed in accordance with the Board of Management meeting rules and handbook

- Board satisfaction with Kakadu Research and Management Advisory Committee and Kakadu Tourism Consultative Committee

Background

As noted in Section 1.5, joint management was established when the lease of land in Stage One of the park was signed between the Kakadu Aboriginal Land Trust and the Director of National Parks in 1978 and the government committed to managing all of the park as if it were Aboriginal land. The lease agreements between the Director and the Kakadu, Jabiluka and Gunlom Aboriginal Land Trusts include obligations on the Director to:

- manage the park to the highest possible standard

- protect the interests of Bininj/Mungguy and areas and things that are important to them

- encourage the maintenance of Bininj/Mungguy traditions

- use traditional skills in park management

- promote Bininj/Mungguy engagement in park management and service delivery

- encourage businesses within the park.

The leases also say the Director will regularly consult the Northern Land Council and Bininj/Mungguy associations about management of the park.

Joint management responsibility for decision-making was formalised when the Board of Management was established (see below). Successful joint management is based on a partnership of trust, commitment, and shared responsibility which involves bringing together Bininj/Mungguy and Balanda knowledge and experience and interweaving the two law systems together in making decisions. Making this work requires Bininj/Mungguy and Balanda learning from each other, respecting each other’s culture and bringing together the different approaches. At the core of shared decision-making is open communication and mutual commitment to looking after country and culture.

Shared decision-making in the park requires consultation and active participation in the process from both Bininj/Mungguy and Balanda to ensure decisions respect cultural protocols and meet obligations under the EPBC Act and other relevant Australian laws.

Under Bininj/Mungguy cultural protocols and practices, Bininj/Mungguy are responsible for making decisions about their country and are guided by customary decision-making structures, seniority and kinship obligations.

‘Bininj laws must be followed, with Balanda law backing up Bininj law.’

Jonathon Nadji, Bunitj clan

Board of Management

The Board of Management for the park was established in 1989 under the NPWC Act and continued under the EPBC Act. The composition of the Board must be agreed between the Minister (who appoints Board members) and the Northern Land Council, but the Act requires a majority of Board members must be Indigenous persons nominated by the traditional owners of land in the park. Bininj/Mungguy representation on the Board covers the geographic spread of Aboriginal people within the Kakadu region as well as the major language groups, and the Board has determined that the Chairperson be appointed from the Aboriginal members of the Board. Under the EPBC Act, the Board of Management has the functions of preparing the management plan with the Director, making decisions concerning implementation of the plan (including allocation of resources and setting priorities), monitoring management of the park and providing advice to the Minister on all aspects of the future development of the park.

Governance workshops and training were held for Board members in 2010 and 2011 to facilitate and support shared decision-making by the Board within the joint management partnership. This resulted in a number of governance documents being produced including Board meeting rules and member handbook.

Director of National Parks

The EBPC Act gives the Director the function of administering, managing and controlling the park and protecting biodiversity and heritage in the park. The Act and the EPBC Regulations give the Director a number of specific powers to assist in the performance of these functions, for example power to determine park entry and use charges (subject to approval of the Minister), to control certain activities and to issue permits. The Director must carry out these functions and use these powers in accordance with this plan.

As noted above the Director has a number of obligations under the current lease agreements with the Kakadu, Jabiluka and Gunlom Aboriginal Land Trusts to protect Bininj/Mungguy interests and culture. Together with the EPBC Act, the leases are key documents for guiding decision-making and the EPBC Act requires this plan to be consistent with the Director’s lease obligations. The full provisions of the leases at the time of preparing this plan are included as Appendix I to this plan. The Park Manager makes day-to-day management decisions and exercises powers on behalf of the Director in accordance with this plan, Board decisions, the EPBC Act and other legislation.

Northern Land Council

The Northern Land Council (NLC), which is established under the Land Rights Act, has broad functions to assist and represent the interests of the traditional Aboriginal owners of land and other Aboriginals. Under the park leases the NLC has a number of specific roles, including to be consulted regularly about the management of the park. Under the EPBC Act the Director is required to consult the NLC about park management generally and in relation to preparation of management plans in particular.

Board consultative committees

To help the Board make informed decisions, it has established the Kakadu Tourism Consultative Committee (KTCC) and the Kakadu Research and Management Advisory Committee (KRMAC). The KTCC provides the Board with advice on tourism issues and the views of tourism stakeholders. The primary purpose of the KRMAC is to provide advice to the Board on research and management issues and priorities for the park. The KRMAC members are researchers with expertise in natural and cultural resource management or tourism, Indigenous economic interests or other areas related to park management.

Management issues

- The Board, Director and park staff need to make decisions and manage the park in accordance with the EPBC Act and Regulations, the leases, this plan, and other Australian laws, but must include Bininj/Mungguy cultural protocols, practices, laws and customs (including clan-based decision-making) to the greatest extent possible.

- At the time of preparing this plan not all the land in the park was Aboriginal land under the Land Rights Act but management to date (including the composition of the Board and previous management plans) has been based on the principle, established when the park was first declared in 1979, of managing the whole park as if it is Aboriginal land.

- Values important to Bininj/Mungguy, as well as other recognised values, need to be understood and protected.

- People involved in decision-making should have equal access to accurate and relevant information.

- Good communication is needed between the joint management partners so that expectations are understood and issues can be resolved.

- The joint management relationship is a dynamic one and changes over time depending on the people involved and their expectations of, and aspirations for, joint management. Regular checks are needed to ensure joint management continues to be successful in the future.

- The Board needs adequate resources to carry out its functions under the EPBC Act.

- Bininj/Mungguy should be consulted appropriately to inform Board decisions.

- Other stakeholders should be consulted in structured and timely ways as far as possible.