October 2018

Prepared by Prepared for

Prepared by Prepared for

West Block and the Dugout Heritage Management Plan 2022

I, Ben Morton, make the following plan under section 341S of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

The name of this plan is the West Block and the Dugout Heritage Management Plan 2022.

Dated 7 March 2022

Ben Morton

Special Minister of State

West Block and the Dugout Heritage Management Plan 2022

Date | Document status | Reviewed by |

June 2018 | Incomplete draft for comment | Peter Lovell Director and Founding Principal, Lovell Chen |

July 2018 | Draft for review | Adam Mornement Associate Principal, Lovell Chen |

August 2018 | Complete draft | Adam Mornement Associate Principal, Lovell Chen |

August 2018 | Report for review by the Australian Heritage Council | Adam Mornement Associate Principal, Lovell Chen |

| | |

Cover: Oblique aerial photograph looking south-east at West Block (then Secretariat no. 2) from Commonwealth Avenue, 1928

(Source: National Archives of Australia)

West Block and the Dugout Heritage Management Plan Prepared for Geocon October 2018 |

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF FIGURES

PROJECT TEAM

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1.0 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background and brief

1.2 Identification of the place

1.2.1 Note regarding orientation

1.3 Parliamentary Zone

1.4 Methodology and document structure

1.5 Statutory heritage controls

1.5.1 Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999

1.6 Non-statutory heritage listings and classifications

1.6.1 National Trust of Australia (ACT)

1.6.2 Register of the National Estate

1.6.3 Register of Significant Twentieth Century Architecture

1.7 Consultation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

1.8 Social values

1.9 Limitations

2.0 UNDERSTANDING THE PLACE

2.1 Pre-European settlement

2.2 The Griffin plan for Canberra

2.3 Early planning for Canberra (1912-1925)

2.3.1 Walter Burley Griffin, Federal Capital Director of Design and Construction (1913-20)

2.3.2 The Federal Capital Advisory Committee (1921-24)

2.3.3 Federal Capital Commission (1925-30)

2.4 The Parliament House Secretariat group (1922-28)

2.4.1 Design and construction

2.4.2 John Smith Murdoch (1862-1945)

2.4.3 Landscaped setting

2.4.4 Charles Weston (1866-1935)

2.5 West Block, 1927-38

2.5.1 Alterations, 1927-38

2.6 World War II, 1940-45

2.6.1 The Dugout

2.6.2 Alterations and additions, 1940-46

2.7 Post-World War II 1946-60s

2.7.1 Alterations and additions, 1946-60s

2.8 Refurbishment, 1970s-80s

2.8.1 Alterations and additions, 1970s-80s

2.9 Recent history, 1988-present

2.10 Existing conditions

2.10.1 Site overview

2.10.2 West Block

2.10.3 The Dugout

2.10.4 Landscaped setting

2.10.5 Views and visual relationships

3.0 ASSESSMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE

3.1 Assessment of historic value

3.1.1 The Commonwealth of Australia

3.1.2 Canberra as the National Capital

3.1.3 The Dugout

3.1.4 Associations

3.2 Assessment of aesthetic value

3.2.1 The Federal Capital style

3.2.2 Landscaped setting

3.3 Assessment of social value

3.4 Assessment against Commonwealth Heritage criteria

3.5 Statement of significance

3.5.1 Summary Statement of Significance

3.5.2 Comment

3.6 Attributes related to significance

4.0 OPPORTUNITIES AND CONSTRAINTS

4.1 Implications arising from significance

4.2 Legislation

4.2.1 Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Australia)

4.2.2 Commonwealth Heritage List

4.2.3 Australian Capital Territory (Planning and Land Management) Act, 1988 (Commonwealth)

4.2.4 Parliament Act, 1974 (Commonwealth)

4.2.5 Utilities Act 2000 (ACT)

4.2.6 National Construction Code (BCA) compliance

4.2.7 Disability Discrimination Act, 1992

4.3 Crown Lease

4.4 Stakeholders

4.4.1 Department of the Environment and Energy

4.4.2 National Capital Authority

4.4.3 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

4.4.4 Associations and special interest groups

4.4.5 General public

4.5 Condition and presentation of built fabric

4.6 Condition and presentation of setting

5.0 CONSERVATION POLICIES AND MANAGEMENT GUIDELINES

5.1 Definitions

5.2 General policies

5.3 Conservation policies

5.4 Use, adaptation and change

5.5 Management policies

5.6 Implementation plan

5.6.1 Monitoring of implementation

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ENDNOTES

APPENDIX A HERITAGE CITATIONS

APPENDIX B HISTORIC DRAWINGS AND DOCUMENTATION

LIST OF FIGURES

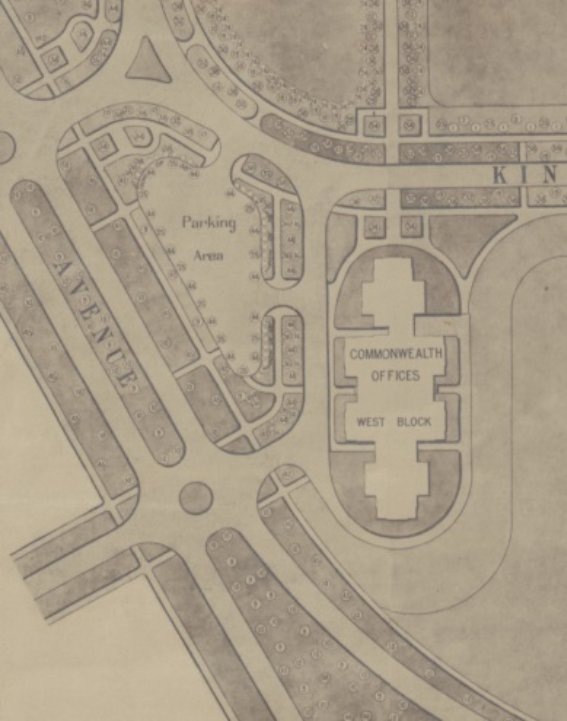

Figure 1 Aerial view of the Parliamentary Triangle: West Block is indicated (17 March 2018)

Figure 2 Plan of survey for Block 3, Section 23 Parkes (part)

Figure 3 Aerial view of West Block and its setting: the Dugout is indicated

Figure 4 The Parliament Zone is hatched

Figure 5 The Government Group: detail of the Griffin’s competition entry, 1911

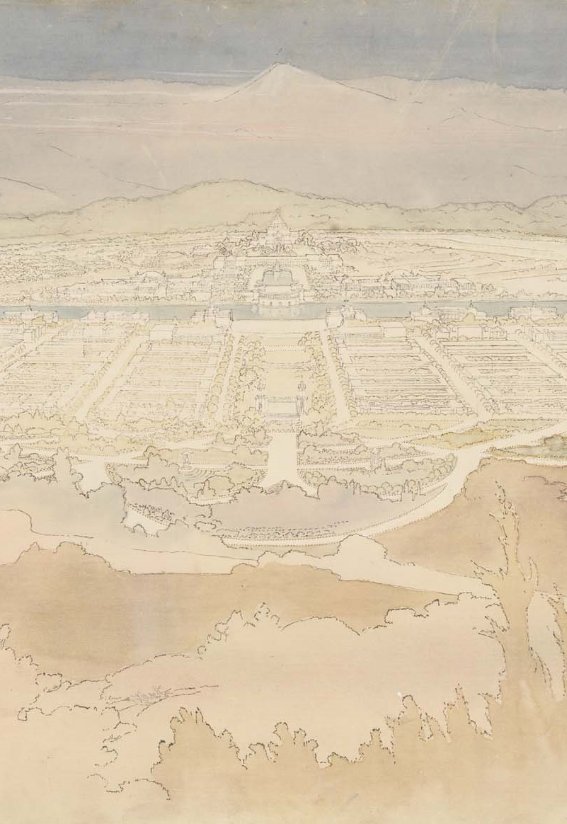

Figure 6 View looking south along the Land Axis from Mount Ainslie, rendering by Marion Mahony Griffin for the 1911 competition

Figure 7 The Departmental Board plan for Canberra, 1912 (part)

Figure 8 Aerial view of south Canberra, 1928: the National Triangle (part) is visible to the left

Figure 9 View of West Block from the north-west, 1929: note the corner balconies and verandahs

Figure 10 View looking south from Mount Ainslie, 1927: the area now known as Anzac Parade is in the centre-ground, with East and West blocks to either side of the Provisional Parliament House

Figure 11 Detail of ‘Permanent Planting for the Governmental Group’, 1928, Commonwealth Avenue (part) is to the left: ‘10’ indicates Cedrus deodara (Himalayan cedar) and ‘9’ indicates Cedrus atlantica (Atlantic cedar)

Figure 12 View looking south-east along Commonwealth Avenue, c. 1940s, with cedar plantings maturing: West Block is visible to the rear

Figure 13 Oblique aerial looking south-west over the Parliamentary Gardens, c. 1928: West Block is visible to the rear of the Provisional Parliament House

Figure 14 Detail of the oblique aerial c. 1928: note the avenue of trees aligned to the north elevation of West Block, and the symmetrically-positioned sentinel poplars either side of Queen Victoria Terrace

Figure 15 Oblique aerial, 1928

Figure 16 Aerial view of West Block, 1950

Figure 17 Public servants in the Prime Minister's Department, West Block, 1928

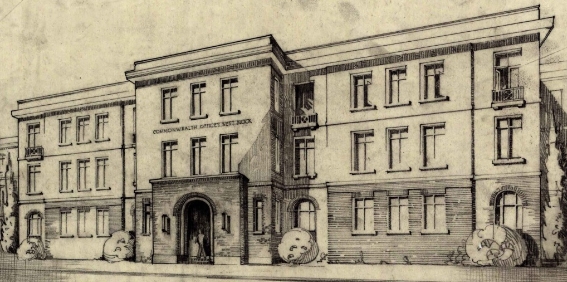

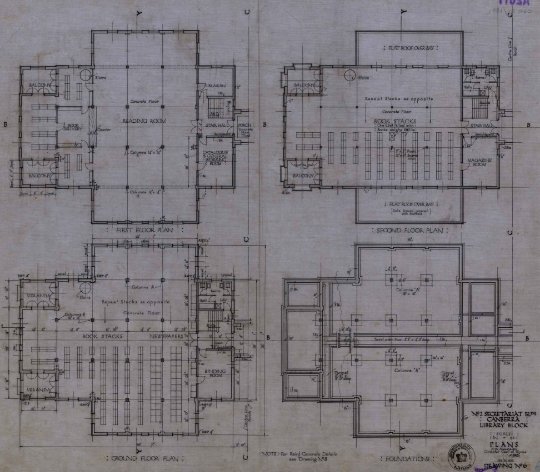

Figure 18 Plans for the National Library at West Block, 1926

Figure 19 Proposed temporary building for the Cables Branch (unbuilt), 1943

Figure 20 ‘D Block’, pictured 1954, as viewed from the south-east

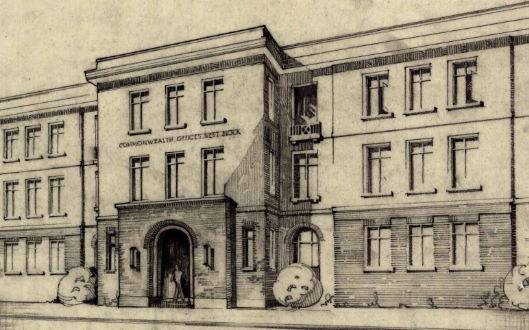

Figure 21 Proposed additional office accommodation and new main entrance, West Block, 1945

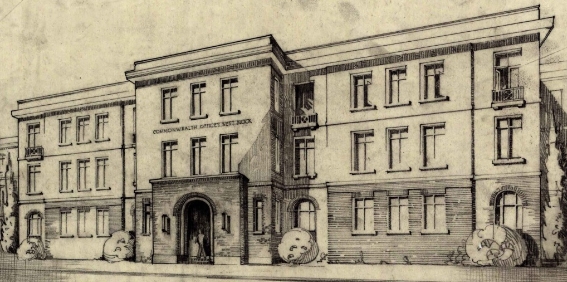

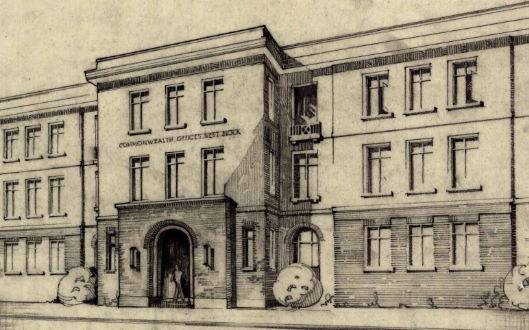

Figure 22 New main entrance to West Block in 1959, showing the original signage ‘Commonwealth Office West Block’

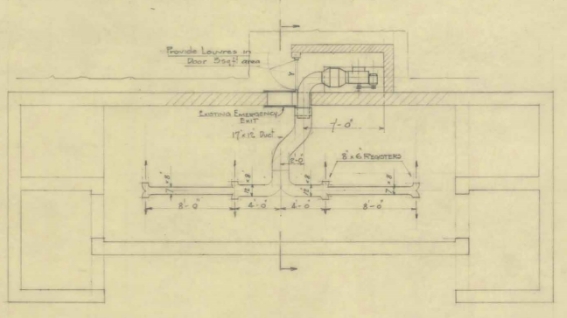

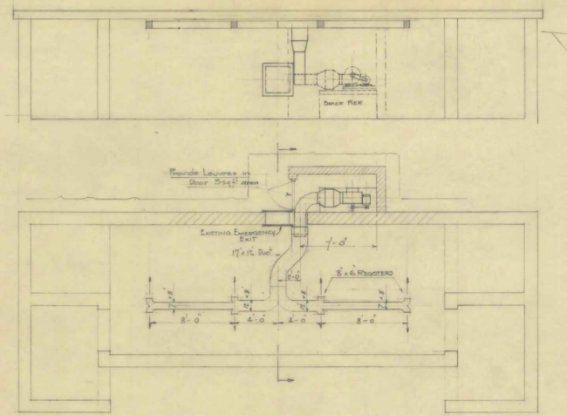

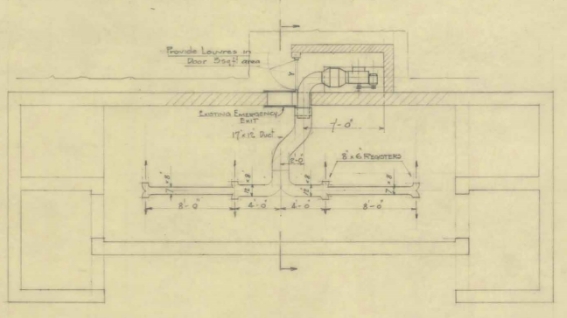

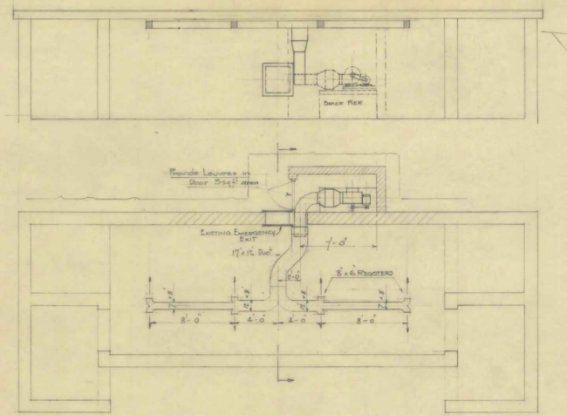

Figure 23 Ventilation and heating was installed at the ‘Dugout’ in 1943, for the adaptation of the air raid shelter to accommodate a Typex decoding machine

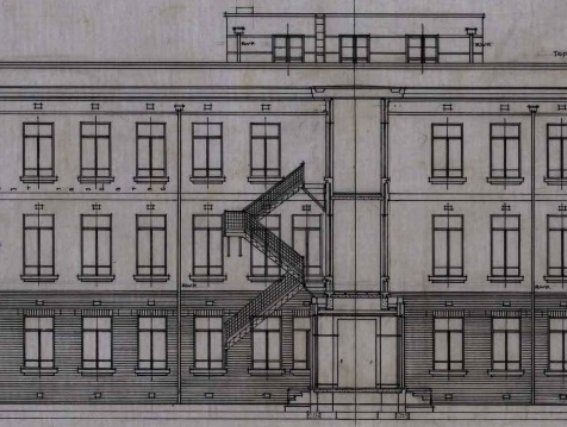

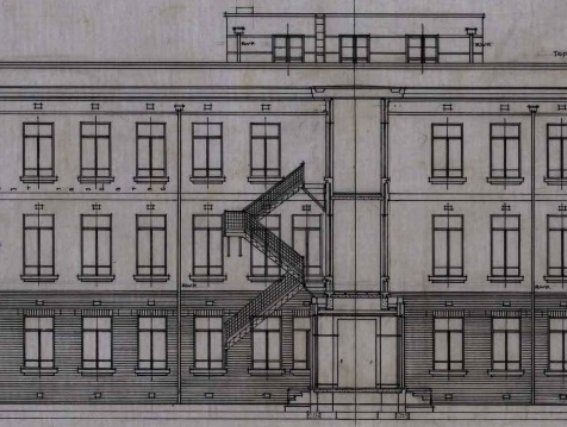

Figure 24 East elevation of B Block, 1944: an external staircase provided access into the building from the Dugout

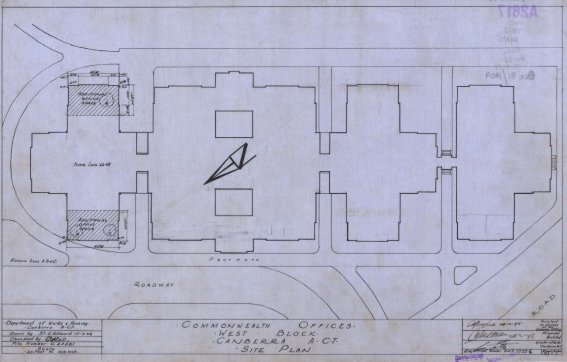

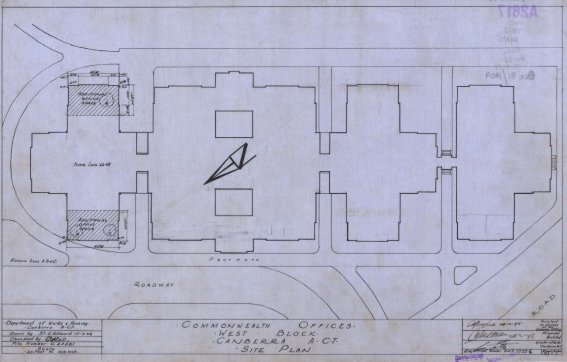

Figure 25 West block – site plan, 1948, showing the extensions made to A block

Figure 26 Sequential development of West Block, ground floor

Figure 27 Sequential development of West Block, First Floor

Figure 28 Sequential development of West Block, Second Floor

Figure 29 Sequential development of West Block, Third Floor/Roof Plan

Figure 30 Ventilation and heating was installed at the ‘Dugout’ in 1943, for the adaptation of the air raid shelter to accommodate a Typex decoding machine

Figure 31 Dugout: view looking north, with the original west elevation at right, and the 1980s screen wall at left

Figure 32 West elevation of the Dugout: the 1980s screen wall is in the foreground

Figure 33 Tree-lined vista extending north from A Block: view looking south to West Block

Figure 34 Native plantings to the east and south-east of West Block

Figure 35 View of West Block from the car park to the east

Figure 36 View of West Block from Commonwealth Avenue, looking south

Figure 37 View of West Block, south elevation, from the slip road to State Circle

Figure 38 West Block (north elevation) as seen from the tree-lined pathway to the north

Figure 39 Typex cypher machines of the type housed in the Dugout, operated by the Women's Auxiliary Air Force (UK)

Figure 40 Mount Stromlo Observatory, established 1924

Figure 41 Albert Hall, Canberra, 1928

Figure 42 Melbourne and Sydney buildings, Civic (1926-27)

Figure 43 Detail of Howard’s vision for a ‘Garden City’

Figure 44 Designated Area Precincts: the Parliamentary Zone is identified as precinct 1

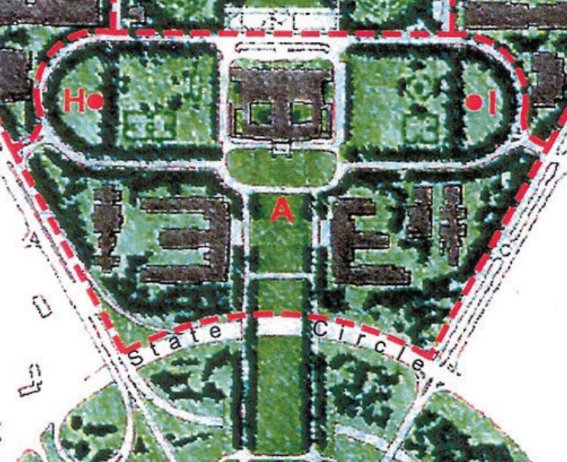

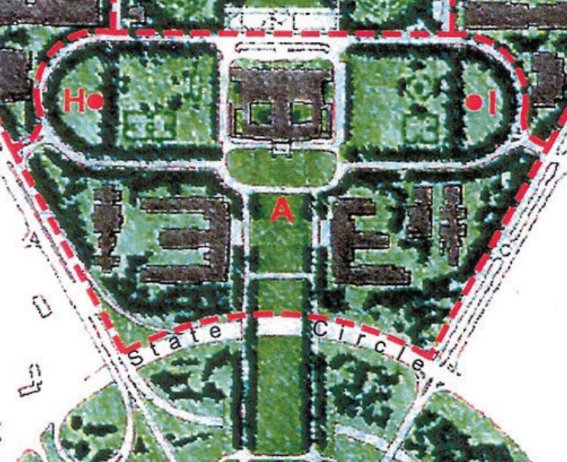

Figure 45 Parliamentary Zone, Indicative Development Plan, detail of the Parliamentary Executive, Campus A (‘H’ is Magna Carta Place, and ‘I’ is Constitution Place)

Figure 46 Perspective view of the Parliamentary Zone ‘campuses’ looking south-west: West Block is indicated

Figure 47 Significant trees and landscape character areas

Figure 48 West Block: heritage curtilage, showing the curtilage extending toward East Block

Figure 49 West elevation of West Block (part), c. 1928: the pull-down awnings in boxed casings were an early addition

Figure 50 West elevation of West Block (part), 1972

Figure 51 Aerial view of West Block: the location of an indicative building envelope is in pink

Figure 52 Lettering reading ‘Commonwealth Offices West Block’ was added over the main entrance in the early post-World War II period

Figure 53 Detail of ‘Permanent Planting for the Governmental Group’, 1928, with the original structured arrangement indicated

Figure 54 Existing interpretation at West Block

PROJECT TEAM

Adam Mornement, Associate Principal, Lovell Chen

Peter Lovell, Director and Founding Principal, Lovell Chen

Felicity Strong, Heritage Consultant, Lovell Chen

Michael Cook, Heritage Consultant, Lovell Chen

Brigitte Samwell, Graphic Design, Lovell Chen

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Eric Martin, Managing Director, Eric Martin and Associates

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This Heritage Management Plan (HMP) for West Block and the Dugout (generally referred to here as West Block) at Block 3, Section 23 Parkes (part), Canberra was commissioned by the Geocon Group. The company signed a 99-year Crown Lease for the property on 20 November 2017. It plans to adapt the redundant three and four-level office building at the site as a hotel.

West Block is included in the Commonwealth Heritage List (CHL place ID 105428), which is established under the Environment Protection Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). This HMP has been prepared in accordance with Schedule 7A of the Commonwealth Environment Protection Biodiversity Conservation Regulations, 2000: ‘Management Plans for Commonwealth Heritage Places’. The overarching objective of Schedule 7A of the EPBC Act is to provide frameworks to inform the future conservation and management of the cultural heritage values of places included in the Commonwealth and National heritage lists. This document also follows the principles and processes set out in heritage best practice guidelines, including the Burra Charter (2013).

Overview of the asset

West Block was designed in 1925, built in 1926-27 and was in use from August 1927. It formed part of the Parliament House Secretariat group, which also includes East Block and the Provisional Parliament House.

West Block comprises a series of four three-storey wings (or blocks) of varying footprint connected on a north-south axis. It was designed in the interwar Stripped Classical style (also referred to as Modern Renaissance). Distinguishing characteristics of the architectural language include horizontal massing, symmetrical façades divided into vertical bays, classical proportions and a general absence of applied detail. It was a pragmatic and well-resolved solution to the challenge of accommodating a variety of official uses and operations within a tight timeframe. The building has been subject to incremental change since 1937-38, when the first major works were carried out, including infilling of the original corner verandahs and balconies. The last phase of external alterations was completed in 1948.

There is a triangular at-grade car park to the west of the building, which is contemporary with the site’s establishment and is within Block 3, Section 23 Parkes (part). A larger car park to the east of West Block, which dates from the late-1950s and is located on higher ground, is not within the site boundary. There is a service road to the west of the West Block, separating the building from the triangular integral car park.

An embankment to the east of the office building dates to 1925-26, when the site was partially levelled. The Dugout, a 1942 air raid shelter, is built into the embankment. At the beginning of 1943, the shelter was adapted to accommodate a Typex cypher machine, used for coding and decoding cables. The Typex machine enabled Prime Minister John Curtin to communicate directly with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and American President Franklin Roosevelt during World War II. The building has been in use as a substation since 1945.

The landscape treatment to the north and west of West Block, including around the triangular car park, was established in the 1920s, as part of the broader landscaping for the south end of the Parliamentary Triangle. Remnants of the formal 1920s landscape treatment, including mature deciduous trees and some hedges, are extant both within the subject site and addressing both sides of Queen Victoria Terrace. The native plantings to the south and south-east of West Block are generally more recent.

The site includes no significant objects or items of moveable heritage.

Findings

The assessment of significance undertaken for this HMP has found that West Block satisfies the CHL threshold for: Criterion A (historical significance), Criterion D (principal characteristics), Criterion E (aesthetic significance), Criterion F (creative/technical significance) and Criterion H (significant associations).

West Block is of historical significance to Australia for its association with Federation. The building is a component of the Parliament House Secretariat group, the first premises purpose-built for Australia’s democratic government. The principal component of the group is the Provisional Parliament House itself, as reflected in its siting on the Land Axis, and its visual prominence within the national capital. West and East blocks were supporting elements. The primary role of these multi-purpose buildings was office accommodation. The buildings within the Parliament House Secretariat group were conceived as temporary, pending the construction of a permanent Parliament House, completed in 1988.

The Dugout is of historical significance as the building from which Prime Minister Curtin communicated with Australia’s allies during World War II, using a Typex cypher machine. The building is also significant as a remnant of the World War II defences introduced within the Parliamentary Zone during World War II.

West Block is significant for demonstrating the principal characteristics of the Federal Capital style, an interpretation of interwar Stripped Classicism which is now strongly associated with Canberra’s establishment phase. Internal evidence of the building’s original/early character and layout is generally limited.

The buildings that make up the Parliament House Secretariat group are symmetrically positioned within a large-scale landscape (the Parliamentary Triangle, south of King Edward Terrace) that was conceived in the 1920s as the centrepiece of the Federal Capital. The landscape of the Parliamentary Triangle, although much altered, is of aesthetic significance. The formality of the planned landscape provides an appropriately distinguished setting for the Provisional Parliament House. It also contributed to the establishment of Canberra’s ‘Garden City’ identity.

The Parliament House Secretariat group is located at the southern end of the Land Axis (Parliament House Vista), a key symbolic and planning component of Walter Burley Griffin’s concept for the National Capital. The three buildings were designed by the office of J S Murdoch, Chief Architect of the Commonwealth Department of Works and Railways, and were sited to reinforce the formal qualities of the Land Axis. The landscape treatment was designed and planted by Thomas Weston, with input from Murdoch. Collectively, the planning and presentation of the Parliament House Secretariat group as a key component of Land Axis is a work of creative (technical) significance.

West Block is significant for its associations with Walter Burley Griffin, J S Murdoch and Charles Weston, each of whom, variously, contributed to the planning, design and setting for the building.

Recommendations

The core recommendations of this HMP are summarised below:

Conservation

Conservation objectives for West Block include:

- Maintaining the external presentation of West Block as a free-standing structure with a general consistency of character and details expressive of the Federal Capital style.

- Conserving original/early (pre-1950) internal features and fabric specifically: the north-south axis that connects the four blocks on each level; the two staircases in B Block; timber ceiling panels where extant in A, B and C blocks, including a section that is known to survive on the ground floor of B Block; and timber structural framing on levels 1 and 2, which provide an insight into the ‘temporary’ (provisional) nature of the building.

- Conserving the Dugout, to the extent of fabric dating to the 1940s, and exploring opportunities to enhance an understanding of the building’s historical significance.

- Maintaining key structural landscape elements, including the original integral car park and the service road to the west of West Block, including a mixed plantation of exotic specimens to the north and west of West Block and native plantings to the east and south-east.

- Maintaining landscape characteristics as established in the 1920s.

- Maintaining trees dating to the 1920s.

Management

- Geocon should comply with all applicable legislation in the management of West Block’s Commonwealth heritage values, including the EPBC Act.

- Programs of priority maintenance, remedial works and cyclical maintenance should form the basis for on-going care of the significant built fabric at West Block.

- The heritage curtilage for West Block should be understood as extending beyond the boundaries of Block 3, Section 23 Parkes (part) to include elements that connect West Block to the broader planned landscape,

- Future uses of West Block, including adaptation as a hotel, should be compatible with the assessed values of the place so that its cultural significance is maintained and conserved. These values are both tangible (built fabric and landscape setting) and intangible (historical significance). The values that relate to tangible elements can be maintained through conservation works and on-going management. The historical values can be maintained through conservation of the original/early (pre-1950) building fabric and landscape elements, supplemented by on-site interpretation.

- Alterations to the Dugout to reveal its original form should be encouraged, supported by in-situ interpretation (see also final bullet point below).

- The extent of change at West Block since 1927 is such that reconstruction to an earlier or original form would be neither viable nor appropriate – the building’s evolved form should be understood as part of its historical significance. There is, however, potential for that process of evolution to continue, subject to the recommendations of this HMP.

- The introduction of new buildings at the subject site should be sensitive to the heritage values of the place, including the presentation of West Block and its siting in relation to the Land Axis.

- Small-scale additions to support a viable and sustainable new use for West Block, such as pergolas or a porte-cochère, should be of generally light weight construction and set clear from the historic building fabric.

- The cultural heritage values of West Block and the Dugout should be actively promoted through a comprehensive package of heritage interpretation.

The character and presentation of Commonwealth Avenue has been subject to almost wholesale change, with the removal of trees to the median strip and to both sides. In response, the NCA has initiated a proposal to re-establish aspects of its original and early character. [6]

This Heritage Management Plan (HMP) has been prepared for the Geocon Group, lease holder of West Block and the Dugout at Block 3, Section 23 Parkes (part). NG Landholdings Hotel Pty Ltd signed a 99-year Crown Lease for West Block on 20 November 2017 and plans to adapt the existing three and four-level office building at the site as a hotel. The site is owned by the West Block Trust (WBT), a discretionary trust the beneficiaries of which are Nick Georgalis, founder and managing director of Geocon, and associated entities/persons. The trustee of WBT is West Block Pty Ltd. Nick Georgalis is the sole director, member and office holder of West Block Pty Ltd.

West Block and the Dugout (generally referred to here as West Block) is included in the Commonwealth Heritage List (CHL) as Place ID: 105428 (see Appendix A for citation). As noted in the CHL citation for the property, West Block satisfies the following criteria Commonwealth Heritage criteria: ‘A, Processes’, ‘B, Rarity’, ‘D, Characteristic values’, ‘E, Aesthetic characteristics’, ‘F, Technical achievement’ and ‘H, Significant people’.

This HMP has been prepared to satisfy Clause 2 ‘e’ part (ii) (a) which requires that the lessee must:

… not later than the day which is 12 months after the date of commencement of the Lease, carry out and provide to the Department of the Environment and Energy a final version of the Heritage Management Plan for its review and approval …

It is consistent with the requirements of Schedules 7A and 7B of the Commonwealth Environment Protection Biodiversity Conservation Regulations, 2000, respectively ‘Management Plans for Commonwealth Heritage Places’ and ‘Commonwealth Heritage management principles’ (see also Section 1.4).

This document supersedes an HMP dated 2014 (but substantially drafted in 2010) for West Block prepared by Eric Martin and Associates Architects.

The primary objectives of this HMP are to:

- Confirm the cultural heritage significance of West Block and the Dugout;

- Provide policies for the conservation of the place, taking into account the care of significant fabric, the appropriate management of hazardous materials and the use and management of the site; and

- Provide a heritage framework to inform future management of the place, including guidance on new works and development.

West Block is located to the south-west of the Provisional Parliament House at the southern apex of the Parliamentary Triangle (Figure 1). The office building was constructed in 1926-27 and in use from August 1927 as part of the Parliament House Secretariat group. East Block and the provisional Parliament House itself are the other components of the group. The three buildings were designed by John Smith Murdoch, Chief Architect of the Commonwealth. West Block, which was originally known as Secretariat No. 2, has been subject to incremental change and evolution over the past 90 years. Its current extent is shown at Figure 2.

The Dugout is a small, single-storey electrical substation to the east of the West Block (Figure 3). It was built in 1942 as an air raid shelter. The building’s significance derives from its adaptation in 1943 to accommodate a Typex cypher machine which enabled secure coded communication between Prime Minister John Curtin and the leaders of Australia’s key allies, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and American President Franklin Roosevelt.

An approximately triangular at-grade carpark is located to the west of Block 3, Section 23 Parkes, and there are remnants of the original 1920s landscaping treatment to all sides of West Block, as well as more recent native plantings to the east and south-east. The subject site covers an area of 1.689ha and includes three easements (see Figure 3).

The axis connecting the four blocks that comprise West Block is oriented on a diagonal to true north – technically north-northeast to south-southwest. For ease of understanding, the elevation facing Queen Victoria Terrace is referred to in this report as north; the elevation oriented to Commonwealth Avenue as west; the elevation facing the embankment and the large car park south-east of the Provisional Parliament House is east; and the elevation oriented towards the New Parliament House is south.

Figure 1 Aerial view of the Parliamentary Triangle: West Block is indicated (17 March 2018)

Source www.nearmap.com, 18 April 2018

Figure 2 Plan of survey for Block 3, Section 23 Parkes (part)

Source: LANData Surveys Pty Ltd, Canberra, May 2017

Figure 3 Aerial view of West Block and its setting: the Dugout is indicated

Source: ACTmap, actmapi.act.gov.au, accessed 18 April 2018

The term Parliamentary Zone in this document, consistent with the Parliament Act 1974 and as amended by the Parliamentary Precincts Act 1988 (Schedule 2, Section 3), captures:

… the area of land bounded by a line commencing at a point where the eastern boundary of Commonwealth Avenue intersects the inner boundary of State Circle and proceeding thence in a northerly direction along the eastern boundary of Commonwealth Avenue until it intersects the southern shore of Lake Burley Griffin, thence in a generally easterly direction along that shore until it intersects the western boundary of Kings Avenue, thence in a south westerly direction along that boundary until it intersects the inner boundary of State Circle, and thence clockwise around that inner boundary to the point of commencement.[7]

This area is illustrated at Figure 4.

Figure 4 The Parliament Zone is hatched

Source: Parliament Act 1974

This HMP broadly follows the principles and processes set out in the Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance, 2013 (The Burra Charter) and its Practice Notes. The Burra Charter establishes a standard of practice for those involved in assessing, managing and undertaking works to places of cultural significance.

Specifically, the report has been prepared in accordance with Schedule 7A of the Commonwealth Environment Protection Biodiversity Conservation Regulations, 2000: ‘Management Plans for Commonwealth Heritage Places’. As a Commonwealth Heritage place, an HMP for West Block must address a range of issues identified in the Regulations to the EPBC Act, at Schedules 7A and 7B. The purpose of these issues is to ensure that the place meets the Commonwealth Heritage Management Principles set out in the Regulations.

Table 1 below sets out the EPBC Act Regulations requirements for management plans and provides a comment about how the requirements are satisfied in the present HMP.

Table 1 EPBC Act Regulation requirements for management plans

EPBC Act Regulations, 2000, Schedule 7a | Relevant section(s) of this HMP |

(a) establish objectives for the identification, protection, conservation, presentation and transmission of the Commonwealth Heritage values of the place | Objectives to identify and conserve the cultural heritage significance of West Block were informed by best practice guides, notably the Burra Charter. These objectives are discussed at Section 1.4, and chapters 4 and 5 of this HMP. |

(b) provide a management framework that includes reference to any statutory requirements and agency mechanisms for the protection of the Commonwealth Heritage values of the place | Statutory requirements and agency mechanisms for the protection of the Commonwealth Heritage values of West Block are identified in chapter 4 with particular reference to the EPBC Act. |

(c) provide a comprehensive description of the place, including information about its location, physical features, condition, historical context and current uses | A description of West Block as it exists is at Chapter 2 ‘Understanding the Place’. A contextual history at Chapter 2 refers to notable changes to West Block, the Dugout and the site’s landscape setting over time. |

(d) provide a description of the Commonwealth Heritage values and any other heritage values of the place | An assessment of significance, including a description of West Block’s Commonwealth Heritage values is at Chapter 3 |

(e) describe the condition of the Commonwealth Heritage values of the place | A description of the site’s historic and aesthetic values is in Chapter 2. |

(f) describe the method used to assess the Commonwealth Heritage values of the place | The assessment of the Commonwealth Heritage values of West Block is based on an understanding of the place (site history and physical description, Chapter 2). |

(g) describe the current management requirements and goals, including proposals for change and any potential pressures on the Commonwealth Heritage values of the place | The proposed adaptation of West Block as a hotel, and issues arising in relation to anticipated change at the place are addressed in policies 15, 16, 17 and 18, Chapter 5. |

(h) have policies to manage the Commonwealth Heritage values of a place, and include in those policies, guidance in relation to the following: | A suite of conservation policies and management guidelines have been prepared to manage the identified Commonwealth Heritage values of West Block. See Chapter 5. |

(i) the management and conservation processes to be used | See ‘General policies’, Section 5.2, Chapter 5. |

(ii) the access and security arrangements, including access to the area for Indigenous people to maintain cultural traditions | See Policy 24. |

(iii) the stakeholder and community consultation and liaison arrangements | Policy 6 in Chapter 5 relates to the requirement for community consultation with the stakeholders identified in Chapter 4. (A draft of this HMP was placed on public exhibition from 9 November to 7 December 2018, through an advertisement in the Australian newspaper (page 33) and the website of Geocon. This opportunity for the community and/or interested parties to comment on the document did not yield any responses). |

(iv) the policies and protocols to ensure that indigenous people participate in the management process | Policy 6, Chapter 5 outlines the requirement for stakeholder consultation, with the Indigenous identified as a stakeholder in section 4.4.3 in Chapter 4 |

(v) the protocols for the management of sensitive information | See Policy 7, Chapter 5. |

(vi) the planning and management of works, development, adaptive reuse and property divestment proposals | Section 5.4 generally relates to the use, adaptation and change, see particularly policies 17 and 18. |

(vii) how unforeseen discoveries or disturbance of heritage are to be managed | Policy 26, Chapter 5 relates to the management of archaeological discoveries on site. |

(viii) how, and under what circumstances, heritage advice is to be obtained | See Policy 4, Chapter 5. |

(ix) how the condition of Commonwealth Heritage values is to be monitored and reported | See Policy 12, Policy 14 and Policy 21, Chapter 6. |

(x) how records of intervention and maintenance of a heritage places register are kept | See Policy 21, Chapter 5. |

(xi) the research, training and resources needed to improve management | See Policy 23, Chapter 5. |

(xii) how heritage values are to be interpreted and promoted | See Policy 25, Chapter 5. |

(i) include an implementation plan | See Section 5.6, Chapter 5 |

(j) show how the implementation of policies will be monitored | See Section 5.6.1, Chapter 5 |

(k) show how the management plan will be reviewed | See Policy 8, Chapter 5. |

West Block and the Dugout is included in the Australian Heritage Council’s CHL as a Listed Place (Place ID: 105428). It has been assessed as satisfying the following criteria: ‘A, Processes’, ‘B, Rarity’, ‘D, Characteristic values’, ‘E, Aesthetic characteristics’, ‘F, Technical achievement’ and ‘H, Significant people’. The citation is included at Appendix A.

West Block is included in the National Trust of Australia’s (ACT) Register of Classified Places. The citation is included at Appendix A.

West Block and the Dugout were included in the Register of the National Estate in August 1987 (RNE 100476). Following amendments to the Australian Heritage Council Act 2003, the RNE was frozen on 19 February 2007, which means that no new places can be added, or removed. Since 2012 the RNE has been maintained on a non-statutory basis as a publicly available archive. The citation is included at Appendix A.

‘West Block Government Offices’ is included in the Register of Significant Twentieth Century Architecture (RSTCA), maintained by the Australian Institute of Architects (RSTCA, place no. R067). It was included in the RSTCA in December 1983 as a place of national significance. The citation is included at Appendix A.

The outcomes of consultation with Representative Aboriginal Organisations (RAO) undertaken in December 2013 have been relied upon for this HMP. The consultation process followed at that time included a meeting on site attended by: Dr Peter Dowling, a consultant engaged in the preparation of an HMP for West Block on behalf of the Department of Finance; Wally Bell of Buru Ngunawal Aboriginal Corporation; and James Mundy of Ngarigu Currawong Clan. A site walk was preceded by discussion of traditional land use and the site’s history generally.

As recorded in the HMP (2014) for West Block:

The consensus of opinion was that there were no concerns regarding Aboriginal cultural heritage for the area. But a need was agreed that the use of the area as a pathway from Black Mountain to the site occupied by New Parliament House should be acknowledged.[8]

Had the outcomes of the 2013 consultation process yielded outcomes that were contested or otherwise contentious, Lovell Chen would have initiated report-specific consultation with RAOs.

No formal appraisal of social values, as might be informed by a community consultation process, was undertaken in the course of this HMP. It is, however, contended that neither West Block nor the Dugout satisfy the CHL threshold for social value. See further discussion at Chapter 3, Section 3.3.

The Dugout is in use as an electrical substation by ActewAGL. During research for this HMP it was not possible to gain access to the building.

As a consequence, it has not been possible to establish the extent to which the building interior has the ability to demonstrate its World War II-era use for coding/decoding messages from key allies.

Commentary regarding the building’s condition in this report is based on external visual inspection.

The following presents a chronological history of key events in the conception, construction, use and development of West Block, with a particular emphasis on the built fabric and landscape setting. Consistent with the Burra Charter, the aim is to gather information about the place sufficient to understand significance.[9]

Architectural drawings relating to the various phases of development are at Appendix B.

Canberra is located on underlying sedimentary and volcanic rock formed over the past 450 million years. Considerable evidence exists in the region of Indigenous occupation, primarily dating to the mid-late Holocence. The Australian Capital Territory is located within the traditional boundary of the Kamberri, a Walgalu-speaking group who occupied the Murrumbidgee west and south west of Lake George at the time of European arrival in the region in the 1820s.[10]

At the time of European settlement, the site of the national capital was native grassland with eucalypt forest on the surrounding hills. With the introduction of pastoral activities in the early nineteenth century, the natural vegetation was largely destroyed by overstocking and clearing of the forests which caused extensive soil erosion. By the time the site was selected for the new capital (discussed below) the land had become degraded and some of the surrounding hills had been largely denuded of tree cover.

Even before Australia became a federated nation, the need for a national capital for the colonies was apparent. A direction to hold land for a capital was included within the Australian Constitution (1901), and in 1908 the area of Yass-Canberra was named as the site of the federal capital. After an extensive survey, the current location of Canberra was selected.

In April 1911 the Minister for Home Affairs, on behalf of the Commonwealth Government, initiated an international competition for designs for the layout of the federal capital. The 137 entries were judged by a three-man panel comprising James Alexander Smith (engineer), John Kirkpatrick (architect) and John Montgomery Coane (licensed surveyor). On 14 May 1912, two of the panel members, (Smith and Kirkpatrick) selected Walter Burley Griffin's entry as the winner, and on 23 May 1912 the Minister for Home Affairs concurred with the majority decision and Griffin was awarded first prize. Entries by Eliel Saarinen (Helsinki) and Alfred Agache (Paris) placed second and third respectively.

It was not the Government’s intention to fully implement the winning design. Rather, the terms of the competition were that, ‘the premiated designs shall become the property of the Government for its unrestricted use, either in whole or in part.’[11] Accordingly, the three winning entries, as well as the scheme placed first by Coane (prepared by Sydney practice Griffiths, Coulter and Caswell) were purchased by the Government.

The Griffin scheme – planned by Walter and rendered by his wife Marion Mahony Griffin – was distinguished by an intimate relationship with the landscape. The central component of the proposal was an equilateral triangle (the National Triangle) whose corners were aligned on topographic outcrops or elevated land, specifically Mount Vernon in the north-west, Mount Kurrajong in the south, and the saddle between Russell Hill and Mount Pleasant in the north-east. The sides of the triangle formed the major avenues connecting the three primary centres of activity in the new city: the national government at the apex, and the municipal and market centres at the east and west of the base respectively.

A series of axes provided a further organisational underpinning for the plan, specifically the Land Axis, Water Axis and the Municipal Axis. The Land Axis formed the central alignment of the plan. The line extended from Mount Ainslie to distant Mount Bimberi via Mount Kurrajong, bisecting the central triangle and tying the city to its site. The formality and definition of this broad central axis was reinforced by the symmetrical siting of buildings at major intersections.

Griffin’s plan for Canberra envisaged the government complex as a symmetrical group of buildings overlooked by Parliament House on Camp Hill at the south (Figure 5). Historian Paul Reid has described the composition:

Griffin’s concept for government is simple: Parliament at the head, courts of justice at the foot and departments on the flanks. The geometric response to topography [however] causes a response. The keyhole-shaped government site has two parts: one dominant (the Kurrajong circle), and the other subordinate (the triangle including Camp Hill). With the axial layout of the Griffin plan, Kurrajong became absolutely dominating. It is the climax of the whole city design, the obvious site for Parliament …[12]

Griffin located Parliament House on the Land Axis, with the Senate and the House of Representatives clearly expressed to east and west of the building mass. Ornamental ponds extended along the balance of the Land Axis to the lake, giving Parliament House a degree of prominence in the city (Figure 6). Capitol Hill (Mount Kurrajong) was terminus of the ensemble, with accommodation for the Governor-General and the Prime Minister either side of a central administration building.[13]

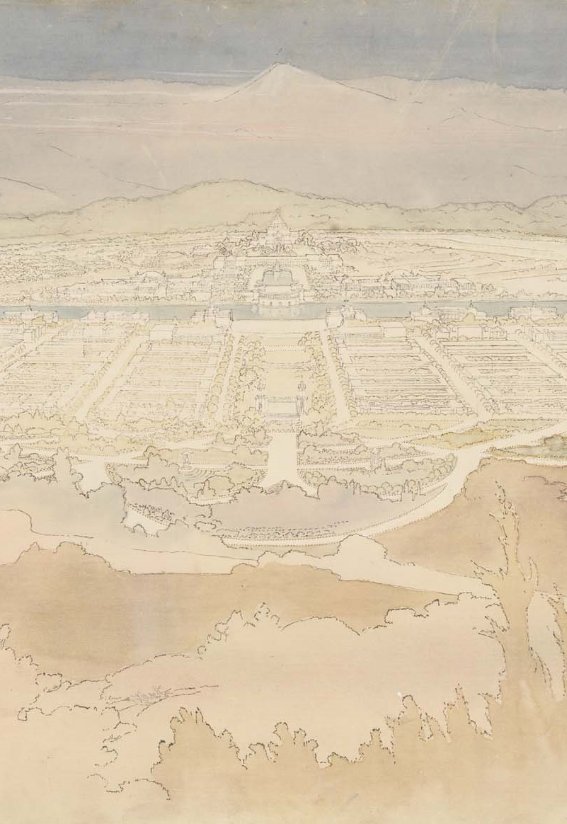

Figure 5 The Government Group: detail of the Griffin’s competition entry, 1911

Source: National Library of Australia, NAA A710, 38

Figure 6 View looking south along the Land Axis from Mount Ainslie, rendering by Marion Mahony Griffin for the 1911 competition

Source: National Archives of Australia, NAA A710 49

Between 1912 and 1925, when the layout of the city of Canberra and its environs was gazetted, the plan for the federal capital was the subject of numerous modifications and revisions. The first of these, in November 1912, was a plan prepared by the Departmental Board, a body charged with implementing the city structure (Figure 7). The Board’s plan, which was approved in 1913, retained Griffin’s Land Axis and the axial siting of Parliament house, but generally incorporated very little of Griffin’s scheme, which was deemed extravagant, costly and impractical.

The first peg of the city was driven on 20 February 1913, six months before the Griffins arrived in Australia (18 August 1913), at the invitation of William Kelly who followed King O’Malley as minister responsible for the national capital following a change of government.

Figure 7 The Departmental Board plan for Canberra, 1912 (part)

Source: National Archives of Australia, NAA A767 1

On 26 August 1913, the Departmental Board met with Walter Burley Griffin in Melbourne and expressed a number of fundamental concerns about the proposal, including its scale and siting.[14] Griffin revised his scheme later that year, seeking to address a number of the matters raised by the Board, but the distance between the architect’s vision and that proposed by the government officials remained significant. The working relationship between the two was also increasingly dysfunctional. Forced to choose between the two, Minister Kelly disbanded the Board in October 1913 and appointed Griffin as Federal Capital Director of Design and Construction on a three-year contract (the contract eventually expired at the end of 1920). Also in 1913, Kelly revoked the approval of the Board plan and formally sanctioned support for Griffin’s revised plan. As noted by heritage consultant Duncan Marshall:

This plan now became the basic planning document, informing all of the Griffins’ later revisions, including the final version of the design prepared in 1918. The final version served, in turn, as the model for the official gazetted plan of 1925 which was to have a long-lasting effect.[15]

In the revised scheme Griffin’s original vision for the central National Triangle was re-established, as was the symmetrical composition of the Government Group to either side of the Land Axis.

Griffin’s tenure as Federal Capital Director of Design was mired by tensions between government officials and departments and hampered by changes in government. In addition, the Great War of 1914-18 was a significant distraction and drain on resources.

The tensions between Griffin and government officials were addressed in a Royal Commission on Federal Capital Administration (1916-17), which found that Griffin had been obstructed.[16] Following the Royal Commission, responsibility for the national capital shifted from the Department of Home Affairs to a new branch within the Department of Home and Territories under Griffin’s control, allowing him a freer rein in his remaining years as the Federal Capital Director of Design.[17]

The pace of development in Canberra between 1913 and the mid-1920s was slow. In the period to 1924, a total of £3.4 million was invested in the construction of the city,[18] and in 1916 and 1917 annual expenditure on capital works was only £8,000.[19] By 1920 development in the city included the Power House complex at Kingston (1916), the brickworks at Yarralumla (1913), Cotter Dam (1912), sewerage works and transmission lines. As noted by Reid, by the time Griffin left Canberra at the end 1920, ‘[his] design was apparent only in some road forming and finishing east of [Mount] Vernon and west of Kurrajong’.[20]

The Federal Capital Advisory Committee (FCAC) was established in January 1921 to advise the Government on the development of Canberra. The Committee recommended a three-phase approach:

- The transfer of Parliament and essential departments to Canberra;

- The development of rail connections, engineering works and the establishment of the central administration of other government departments; and

- The damming of the Molonglo River and construction of major architectural projects.[21]

The FCAC’s role was primarily advisory. Works were undertaken by the executive officers of the Departments of Home & Territories and Works & Railways, and subsequently by the Federal Capital Commission (FCC, Section 2.3.3).

Planning for the transfer of Parliament commenced in 1921. From the outset, there was broad acceptance that the new Parliament House would be temporary. Construction of a permanent structure would be both costly (a pertinent consideration in the context of managing post-war debt) and time-consuming, potentially delaying the transfer of Parliament for many years. Options canvassed in 1921 and 1922 included construction of a Conference Hall that could be augmented for use as a Parliament House when required, and a building of demonstrably temporary character – perhaps built of corrugated sheet metal, fibro-cement of weatherboard – that might serve for 10-20 years before replacement.[22] Discussion also focused on whether the city would evolve around the temporary building, or whether the location of the permanent structure would be the key determinant for the city’s evolution. This question required consideration of how temporary the provisional Parliament House would be. That is to say, would it be removed or repurposed when the permanent structure was completed?

In February-March 1923, a Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works considered the issue and interviewed approximately 50 witnesses. The outcome was a report in July 1923 with two options: a nucleus of permanent buildings for Parliamentary use located on Camp Hill, to be expanded as required; and a provisional structure on the north-facing slope of Camp Hill. In August 1923 the Government, anxious to expedite the relocation of Parliament, selected the provisional option, for which a design was already underway (see 2.4).[23] The first sod was turned on 28 August 1923.[24]

The Government established the Federal Capital Commission (FCC) under the Seat of Government (Administration) Act of 1924. The FFC’s immediate task was to oversee the relocation of Parliament from Melbourne to Canberra. The FCC was also responsible for the gazettal of the Griffin plan of 1918.

Griffin’s plan was, in the main, ignored by the FCC, as was his recommended pattern of settlement. The FCC chose to focus on the delivery of isolated buildings; Griffin’s intent had been to concentrate development around the Municipal Axis (Constitution Avenue). The FCC promoted the development of an ‘Initial City’ to the south of the Molonglo River flood plain, close to the Civic Centre indicated on the Departmental Board plan of 1913; Griffin had recommended that the core of the city be located around Mount Vernon, the Civic Centre indicated on his original competition entry.

The FCC was a dynamic, fast-acting agency which oversaw the first concerted wave of development at Canberra. By the time it was wound up in 1930 development delivered by the FCC south of the Molonglo River valley included, but was not limited to:

- The ‘Initial City’, including the present suburbs of Kingston, Griffith, Barton and Forrest

- The Provisional Parliament House and two Secretariat buildings (East and West blocks), collectively the Parliament House Secretariat group (see Section 2.4)

- Albert Hall

- Hotel Canberra

The 1923 decision to relocate Parliament from Melbourne to Canberra was the catalyst for an enormous logistical exercise of bureaucracy and construction. Within the space of only four years Canberra was transformed from two nascent communities (or villages) either side of the Molonglo River valley into the seat of national government with facilities and amenities to support the population influx.

The provision of office space to accommodate Government departments was considered from early 1923. An early option, put forward by the FCAC, was for the construction of 18 temporary buildings connected by walk-ways and with a central refectory on a site to the north-west of the provisional Parliament House.[25] The proposal was not supported by the Public Works Committee (PWC) which in July 1923 recommended to Parliament the construction of two two-storey buildings to the south of the provisional Parliament House. The PWC’s advice was for:

… two units of two-storied brick or concrete buildings on the east and west of the two blocks to the north of the proposed Parliament House … If this is to be done [the Committee considered that] two units of permanent buildings [would] be available approximately 1,000 feet [c. 350 metres] apart, and a similar distance from the permanent Parliament House site on Camp Hill, and in positions allocated for office purposes on the accepted plan.[26]

The FCAC did not support the PWC’s recommendation, and instead drafted competition terms for one permanent administration building, on a site to the north-east of the provisional Parliament House. A design competition for this building was held in 1924 and was won by Sydney architect George Sydney Jones.[27] His design was modified extensively after his sudden death in 1927.[28] The Administrative Building, now known as the John Gorton Building, was not completed until after World War II and was the largest office building in Australia at the time.[29]

Figure 8 Aerial view of south Canberra, 1928: the National Triangle (part) is visible to the left

Source: National Library of Australia, nla.obj-232839573

As the new permanent Administration Building could not be completed before the first session of Parliament a ‘Secretariat Scheme’ was put forward as an alternative. This would see a nucleus of each Department temporarily relocated to Canberra to assist with Parliamentary work.[30] Although it was recognised that this arrangement may cause some additional administrative burden for the departments, it was considered the best way to balance the requirement for space and the conflicting views about permanence of new buildings.[31]

This scheme was approved by the Minister and the recommendations made by the PWC in 1923 were ultimately implemented – although the buildings as completed were primarily of three levels, not two.

As noted, the Parliament House Secretariat group is comprised of: the provisional Parliament House, East Block and West Block. Each was designed by the Public Works Department under the leadership of Commonwealth Architect John Smith Murdoch and built between 1922 and 1928 (see Section 2.4.2). They were the first buildings completed in the Parliamentary Triangle.

The decision to construct a provisional Parliament House on the Land Axis below (to the north of) Camp Hill, leaving Camp Hill itself for a permanent Parliament building, had a bearing on the height and massing of the temporary structure; views along the Land Axis were to be unimpeded by the temporary building. It also influenced the character and massing of East and West blocks.

In 1924, Murdoch described the Secretariat buildings to the Parliamentary Standing Committee for Public Works:

The two buildings will remain a symmetrical balance with the Provisional Parliament House. While being architecturally sympathetic with the Provisional Parliament House their size will be subordinated to the larger structure. The style is Modern Renaissance, to which the British and Americans are now working. It is a style which depends on proportions and lines rather than details.[32]

Additional information about the design approach was provided by Colonel P T Owen, Director General of Works and Railways in evidence to the Standing Committee:

The general idea is to avoid the domestic in favour of the Official style so far as may be compatible with reasonable expenditure …. A tiled roof for an official building would be regarded as ‘fussy’ although it would be quite correct for hotels and residences … I believe the flat roofs of the Secretariat buildings can be made very beautiful in this way.[33]

Of the two, the building now known as East Block, was completed first, in 1927. ‘Secretariat No. 1’ provided 2,579 square metres (27,760 square feet) of floor space and accommodated a telephone exchange, post office and space for 150 staff. It was anticipated that the building might eventually be used as offices for Members of Parliament.[34] Today it houses the National Archives of Australia.

In January 1925 the FCC Architects Branch reported that the construction of West Block had commenced:

Steady progress has been made by the contractors, Messrs Hutcherson Bros, in the erection of West Block (Secretariat No. 2), and the completion of the central blocks and south block should be affected by the end of July. In order to give proper divisions for the various Departments who will be occupying this building, a large amount of coke breeze partitions [a light concrete building block made with cinder aggregate] have been erected and Ministerial Office(s) have been panelled. The various mechanical services covering lifts, heating, electrical installation, and fire alarm system, are well advanced, and in some cases are now completed.[35]

It is assumed that construction would have been preceded by excavation works to level the sloping site, creating the embankment that remains to the east of West Block.

Although there was a preference for the two Secretariat buildings to be completed in time for the official opening of Parliament in May 1927, only East Block was ready in time.[36] The fit-out of West Block was at least partially completed in August 1927, as reported in the ‘Canberra News’ section The Week periodical.[37]

Distinguishing characteristics of the architectural language adopted by Murdoch for the two buildings included the following (see Figure 9 and 1926 drawings at Appendix A):

- Horizontal massing

- Symmetrical façade divided into vertical bays

- Classical proportions

- Plinths and ground level treatments of face brickwork, with the upper levels rendered and painted white

- Corner balconies and verandahs

- A general absence of applied details, an exception being the Greek-pattern metal railings to the balconies and verandahs

- Screened courtyards

- Flat roof areas concealed by parapets

The design response was a pragmatic and well-resolved solution to the challenge of accommodating a variety of uses quickly. The buildings are architecturally unpretentious, adopting a neutral, or official character; by the mid-twentieth century, the two buildings were recognised as early and influential examples of the Federal Capital style. See Section 3.2.1 for discussion of the Federal Capital style in Chapter 3).

While the two buildings were not mirror images in plan – possibly relating to their original uses, which were quite distinct (see discussion of West Block’s original occupants at Section 2.5) – both East Block and West Block are arranged on a north-south axis with main entrances on the east-west axis, perpendicular to the Land Axis, from which they are equidistant (Figure 10). The arrangement of blocks of varying sizes on an axial alignment provided for a degree of flexibility, enabling change and alterations without abstracting the formal presentation and architectural character of the building complexes.

Figure 9 View of West Block from the north-west, 1929: note the corner balconies and verandahs

Source: National Archives of Australia, NAA A3560, 5426

Figure 10 View looking south from Mount Ainslie, 1927: the area now known as Anzac Parade is in the centre-ground, with East and West blocks to either side of the Provisional Parliament House

Source: National Archives of Australia, NAA A3560, 908

The majority of buildings for Canberra’s establishment phase (1920s) were designed by Public Works Department (PWD) staff based in Melbourne and Melbourne-based architectural practices. Among them, the principal voice was John Smith Murdoch, a Scottish architect who migrated to Victoria in 1885. Murdoch joined the Commonwealth Department of Home Affairs in 1904, as a senior clerk in the Public Works Branch. Ten years later he was promoted to the title of Commonwealth Architect, and in 1919 he became Chief Architect of the Commonwealth Department of Works and Railways.[38]

Murdoch and his department were prolific during the early decades of the twentieth century, designing Commonwealth facilities across the country in a variety of styles. Murdoch’s design for the Commonwealth Offices in Treasury Place, Melbourne – the first purpose-built premises of the Commonwealth Treasury and Cabinet departments – was inspired by the Edwardian Baroque. Murdoch, as the senior Commonwealth architect, was also closely involved in planning for the federal capital.

His work in Canberra adopted a quite distinct idiom, a synthesis of revivalist and overseas styles including neo-Georgian, Colonial Revival, Spanish Mission and the Prairie Style. This synthesis has come to be known as the Federal Capital style.

Works attributed to Murdoch in Canberra, aside from the provisional Parliament House and the two Secretariat buildings, include: the Canberra and Kurrajong hotels (1924 and 1926 respectively), to accommodate public servants required to relocate to the Canberra; the Kingston Power House (1916); and the first buildings at the Mount Stromlo Observatory. The residential suburbs of Reid, Ainslie, Forrest and Barton also evolved from the same cycle of construction.[39]

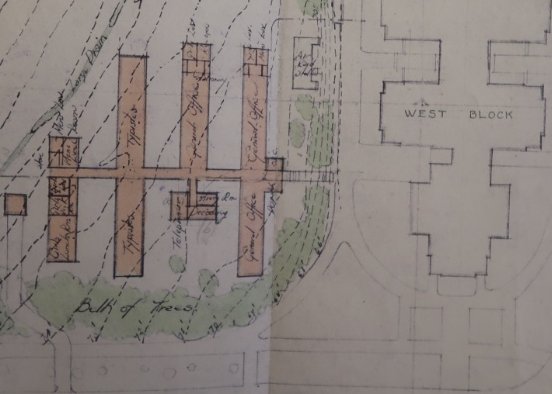

The original landscaping treatments to the west, north and north-east of West Block were among the earliest in Canberra. The works were arranged and planted by Charles Weston, officer-in-charge of afforestation at the national capital, with support and advice from others (see Section 2.4.4).

A key reference for the following section is a 1928 plan of ‘permanent plantings’ within the ‘Government Group’ at Appendix A (see also detail at Figure 11). Photographs c. 1928 confirm that West Block’s setting was initially planted to a layout which accords with what is shown in the 1928 plan.

A discussion of existing landscape conditions at, within and around West Block is at Section 2.10.4.

Commonwealth Avenue

Plantings to either side of Commonwealth Avenue were established from the beginning of 1922. The median strip was planted with two rows of Himalayan cedar (Cedrus deodara) with a single row of Atlantic cedar (Cedrus atlantica) in the centre. Further rows of Himalayan cedar were planted to the east and west sides of the Avenue with rows of Chinese elms (Ulmus chinensis) behind. The outcome was both a formal avenue and a wind break to protect the Parliamentary Administrative Area (Figure 12). Weston also introduced shrubs and ground covers, including roses in the area.[40] The 1920s planting treatment and landscape character of Commonwealth Avenue has been all but lost over time.

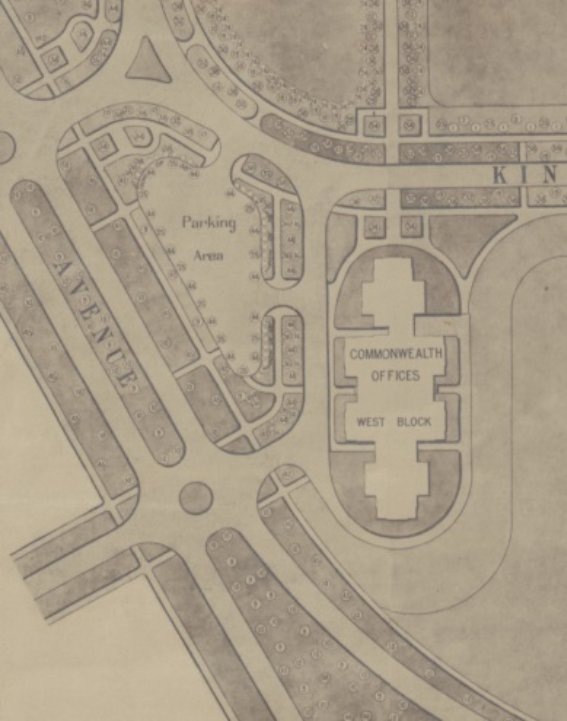

The Parliamentary Triangle, including West Block

The FCAC considered the landscape treatment of the south end of the Parliamentary Triangle (also referred to as the Parliamentary Gardens), including West and East blocks, as the centrepiece of the Federal Capital.[41] The approximately 35-hectare area bounded by Kings and Commonwealth avenues, State Circle and King Edward Terrace was almost entirely denuded, with the exception of some native vegetation on Mount Kurrajong and Camp Hill (discussed below). Beautification was required to provide a suitably distinguished setting for Parliamentary proceedings, and to manage the prevailing winds.

As noted by John Gray in this doctoral thesis on Charles Weston, ‘[By 1924] the Federal Capital Advisory Committee decided the design of the gardens should reflect the formality of the Provisional Parliament House [then under construction], be on … strictly formal lines and include a body of ornamental water’.[42] Plantings were used to framed vistas and create ‘outdoor rooms’ (Figure 13).

The selection of plantings and their final arrangement was the work of Weston, with input from Murdoch, who had instructed the use of poplars to define the Land Axis, key entrances to the Parliamentary Triangle and intersections within it.[43] Murdoch’s preference was for the balance of the trees to be lower than the poplars and widely-spaced, ‘… the idea being that the comparatively flat buildings will not be unduly dwarfed or views of them too much obscured by trees’.[44]

The poplars were introduced between June and August 1925, with the balance of planting assumed to have been completed by November 1926, when Weston retired. Planted in pairs or fours to address major axial pathways and intersections, each poplar was situated in a square or roughly squared enclosure, edged with low privet hedges.[45]

The selection of poplars as a primary species effectively denied any potential for the gardens to develop a distinctly Australian character, as had been contemplated by the FCAC and others. Native trees and shrubs were, however, selected for new plantings in the vicinity of Camp Hill and Mount Kurrajong (see discussion below), and were employed by Weston in tertiary roles within the Parliamentary Triangle’s tree plantings.

While Weston’s selection of specimen conifers for many of the structural plantings within the Parliamentary Triangle landscape, including Deodar cedar (Cedrus deodara) and Atlantic cedar (Cedrus atlantica), was at odds with Murdoch’s preference for low-growing specimens, it was consistent with his own vision for the city. As noted at Section 2.4.4, Weston had anticipated that cedars would form the chief arboreal feature of the city in 1917.[46] Another variation to Murdoch’s preferred outcome was the density of plantings, with rows of closely-planted trees sometimes four deep. John Gray suggests that, ‘[Weston’s deliberate over-planting] had in mind a quick effect and possible species performance difficulties. He may have assumed a thinning in about 20 years’.[47]

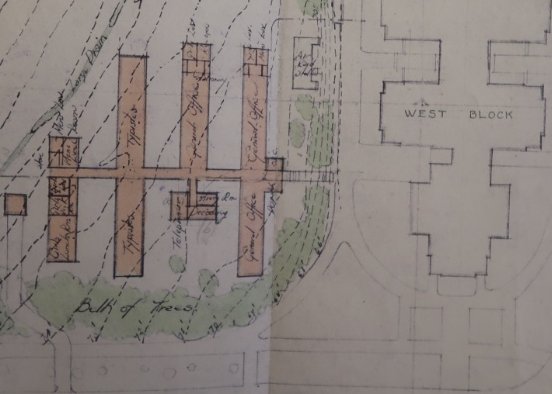

The landscape treatments around East and West blocks were critical to the overall composition of the Parliamentary Gardens landscape. As described by Eric Martin et al, ‘[They form] symmetrical anchors behind and either side of the 1927 Provisional Parliament House … the longitudinal axis of each block is extrapolated further with each northern pavilion [A Block at West Block] addressing an extended axial vista’ (Figure 14).[48] Each block was situated to relate to the Provisional Parliament House and to its corresponding formal axis, while being largely invisible from each other as a consequence of the topography of the Camp Hill situated between them.

At West Block, fast-growing Lombardy poplars (Populus nigra ‘Italica’, described in the 1928 Plan of Permanent Planting as Populus pyramidalis) were planted in accordance with Murdoch’s instruction, in small square planting beds, serving to mark and extend the axial vista, and to frame views of the building’s north elevation. The pairing at the north end of West Block mirrored an identical planting already established across Queen Victoria Terrace to the north. To the west, similar pairs of Lombardy Poplars, also planted earlier, addressed the intersection of the Terrace with Commonwealth Avenue.

One of the original Lombardy poplars marking the northern axis survives within the West Block curtilage, although the pair of square landscape enclosures have been removed. On the north side of Queen Victoria Terrace, the corresponding pair of trees has been replaced in their original locations with new Poplar specimens, and the square enclosures have been maintained with the low hedging as originally conceived. The pair of Lombardy poplars once located at the north end of the West Block car park, aligned with Commonwealth Avenue, have not survived.

Along both sides of Queen Victoria Terrace, between these landmarks and extending to the east, mixed avenue plantings of White poplar (Populus alba), Pin oak (Quercus palustris) and Lawson’s cypress (Chamaecyparis lawsoniana) reinforced the precinct’s formality. Some of these avenue trees appear to have survived to the present day; others have been replaced.

Around West Block itself, a variety of poplars, elms and cypress trees were planted, and eucalypts (Eucalyptus globulus) were introduced in the courtyards to the east and west of B Block.

The other key feature of the West Block precinct was the integral car park to the west. This triangular space was surrounded by a pedestrian walkway. Beginning at the centre of this triangular space, an inner ring of shade trees was planted within the periphery of the car park surface, consisting of alternating American elms (Ulmus americana) and Black ash (Fraxinus nigra, then described as Fraxinus sambucifolia). Beyond this ring, the perimeter beds located between the car park and the pedestrian walkways were planted with two distinctive treatments. The north and east sides of the car park were closely planted with Pin oaks, developing a visual screen to reduce the prominence of the car park in views from the landscape west of Parliament House and from West Block itself. Meanwhile, the south-west side of the car park triangle was completed with a broadly spaced row of alternating Atlantic cedar and Giant redwood (Sequiadendron giganteum, then described as Sequoia gigantea), continuing a more extensive double row of these trees which was planted on the next landscaped block along Commonwealth Avenue to the northwest. This broadly-spaced treatment, in contrast to the density of plantings on the sides of the car park proximate to Queen Victoria Terrace, provided a degree of visual permeability to drivers on Commonwealth Avenue during their final approach to the Parliamentary Triangle.

An additional row of American Elms was established on the western boulevard of the service road, directly opposite West Block, interplanted with mixed pairs of Mountain Ash (Sorbus aucuparia, then described as Pyrus acuparia) and Mexican Cypress (Cupressus lusitanica, then described as Cupressus knightiana).

The aerial photographic record indicates that a reconfiguration of the car park layout occurred at some stage after 1985. Despite this, portions of the original car park planting layout have been retained to the present day, either in the form of original trees planted in the late 1920s, or as sympathetic replacements established somewhat later in the place of deceased original stock. These retentions include much of the Pin Oak screen on the Queen Victoria Terrace side of the car park (likely comprising a mix of original and replacement stock), as well as a small number of mature Elm trees on the western boulevard of the service road which appear to represent the original American Elm planting. The inner ring planting of elms and ash within the original triangular car park has been retained in a fragmentary form after the recent reconfiguration, represented by a small number of Elm trees located on the perimeter of the paved area and in island beds within it. Some of these trees are certainly later replacement plantings some may be original American Elms.

Figure 11 Detail of ‘Permanent Planting for the Governmental Group’, 1928, Commonwealth Avenue (part) is to the left: ‘10’ indicates Cedrus deodara (Himalayan cedar) and ‘9’ indicates Cedrus atlantica (Atlantic cedar)

Source: National Library of Australia, nla.obj-230044722

Figure 12 View looking south-east along Commonwealth Avenue, c. 1940s, with cedar plantings maturing: West Block is visible to the rear

Source: National Archives of Australia, NAA A3560, 3182

Figure 13 Oblique aerial looking south-west over the Parliamentary Gardens, c. 1928: West Block is visible to the rear of the Provisional Parliament House

Source: National Archives of Australia, NAA A3560, 3268

Figure 14 Detail of the oblique aerial c. 1928: note the avenue of trees aligned to the north elevation of West Block, and the symmetrically-positioned sentinel poplars either side of Queen Victoria Terrace

Source: National Archives of Australia, NAA A3560, 3268

Figure 15 Oblique aerial, 1928

Source: National Archives of Australia, NAA A3560 7712

Figure 16 Aerial view of West Block, 1950

Source: ACT Planning and Land Authority

The 1920s planting treatment was generally extant in 1950, as shown in aerial view at Figure 16. Today, a fraction of the original plantings survive. As is the case elsewhere within the Parliamentary Gardens, the extant plantation is conspicuously thinner and also less diverse, having consolidated from the original experimental plantation to those trees which have proven most hardy to the local climate and planting conditions.

As in other places in Australia, certain trees have proved to have generally shorter lifespans than in their indigenous conditions, including the Giant redwoods which the photographic record shows were initially successful in the West Block planting. As a consequence of either their planting position or of the impact of climate stressors and periods of drought, these trees have been lost within the West Block planting, excepting a single specimen which may be a somewhat younger replacement planting for a failure in the original stock.[49] In a similar fashion, the formal plantings of Lombardy poplar have performed to their typical lifespan as a fast-growing species in Australia, and deceased trees in the formal arrangement have in some places within the Parliamentary Triangle been appropriately replaced with new stock (as has been done on Queen Victoria Terrace opposite West Block).

Despite these challenges, a number of original specimens have been retained within the planted landscape integral to West Block. In addition to the single Lombardy poplar, the four surrounding Arizona cypresses are original trees which maintain the formal setting of the building in relation to the formal axis. Atlantic cedars retained adjacent to Commonwealth Drive similarly maintain a sense of the original treatment of this face of the site, along with the single Giant redwood survivor. Although the car park has been altered relatively recently, retained or replanted specimens and groups of Pin Oak and Elm continue to serve as the amenity and screening planting for which they were originally conceived.

Camp Hill and Mount Kurrajong

In contrast to the Beaux Arts-inspired formality of the Parliamentary Administrative Area, the FCAC adopted the principle of retaining the existing open landscape of indigenous trees on Mount Kurrajong and Camp Hill, respectively located to the south-east and east of West Block (see Figure 13),[50] and reinforcing this with further plantings of native trees, shrubs and groundcovers. The front edge of Camp Hill, facing the provisional Parliament House, may have been mass planted with the ‘Mixed Acacias’ labelled on the 1928 plan; a massed planting in this location is certainly visible in c. 1928 views across the precinct (Figure 13) and was later extended to the embankment immediately east of West Block[51] before gradual attrition and loss to subsequent developments and changing land management practices.

Despite the construction of the new Parliament House and the Federation Mall land bridge connecting the old and new Parliament Houses, and a modern car park to the immediate east of West Block, this landscape character and its rationale endures.

During the early 1920s, the character of Canberra as a city in the landscape was given form by horticulturalist Thomas Charles George Weston (generally known as Charles). Weston was officer-in-charge of Afforestation (later Parks and Gardens) at the national capital from 1913 to 1926. He was an island of continuity during a period of rapid change in the management and administration of the emerging city.

Weston’s challenge, as noted in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, was:

… to create an urban landscape [at the remote, infertile, windy and rabbit infested location] consonant with the capital city to be built at Canberra. He was also expected to establish a local forestry industry. Weston set down on paper his four objectives: to establish a first-class nursery, to raise stocks of plants likely to prove suitable, to reserve all local hilltops and improve their tree cover, and to seek out and procure useful seeds.[52]

His work in Canberra fell into two phases. The first, from 1913 to 1920, was focussed on the establishment of nurseries and plant propagation. The second, from 1920 to 1926, was focussed on planting and landscape development.[53]

In general, Weston favoured conifers as a key structure planting. In 1917 he stated that three cedars, Deodar, Atlantic and Lebanon (Cedrus deodara, Cedrus atlantica and Cedrus libani) would be useful as the chief arboreal feature of the city.[54] He also pioneered the use of several eucalypts such as Brittle Gum (Eucalyptus mannifera) and Argyle Apple (Eucalyptus cinerea).

Weston’s approach to formal avenue plantings was to use one predominant species, often adding a smaller scale tree that would give seasonal colour, such as an avenue of Blue Gum (Eucalyptus bicostata) with Flowering Cherry Plum (Prunus cerasifera ‘Nigra’). A variation on this approach was to use a conifer, such as a cypress, cedar or pine, as the major planting. In some instances a Kurrajong (Brachychiton populneus) was used as the smaller tree.[55]

Weston planted parks and reserves in a less formal manner. The style of planting employed in these reserves followed the Garden City style and was a notable departure from Griffin’s intentions for the city.[56] In this regard. Weston is likely to have been influenced by John Sulman (1849-1934), an architect who was prominent in shaping ideas on town planning in Australia during the period leading to Canberra’s inception. He served as chairman of the FCAC from 1921 to 1924. As noted by the late landscape architect Peter Harrison, author of Walter Burley Griffin: Landscape Architect (1995) Sulman, ‘required that Griffin's conception of the capital as a city of monumental buildings be modified, that it should be regarded in the early period of its existence more as a Garden Town, the erection of the permanent buildings being deferred … until economic conditions might be more favourable’.[57]

The first departments transferred from Melbourne to West Block were the Prime Minister’s Department, the Department of Home and Territories, the Department of the Treasury, the Attorney General’s Department and the Official Secretary to the Governor-General (Figure 17). The National Library was accommodated in A Block, at the north end of the building.[58] The inclusion of office space for the Prime Minister’s Department was due to the distance of Yarralumla House from Canberra’s administrative centre.

Although the first Cabinet meeting in Canberra was held at Yarralumla on 30 January 1924, the first Cabinet meetings after the Provisional Parliament House was opened in May 1927 were held in West Block.[59] The use of West Block for Cabinet meetings outside sitting weeks – when the Cabinet Room in Parliament House was used for its convenient location adjacent to the Prime Minister’s office – persisted until 1932, when the Lyons’ Government transferred it permanently.[60] The location of the space at West Block that hosted Cabinet meetings between 1928 and 1932 is not annotated on historic drawings and has not been identified during research for this HMP.

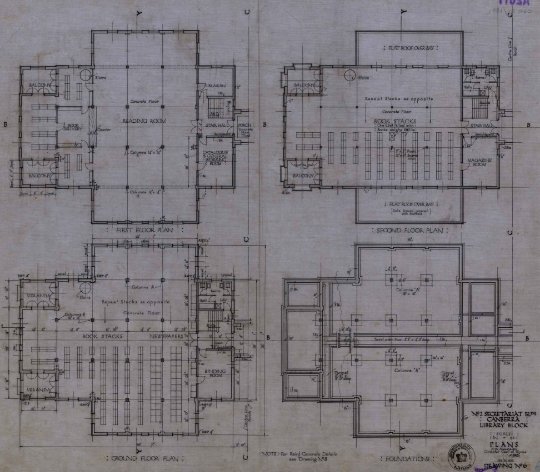

The relocation of the National Library from Melbourne to Canberra coincided with the transfer of Parliament to the Provisional Parliament House. The first incarnation of the national library was the Commonwealth Parliamentary Library in 1902, which was attached to the Victorian Parliamentary Library in Melbourne.[61] The Victorian parliamentary librarian acted as a ‘librarian on loan’ to the Commonwealth government until the library was relocated to Canberra in 1927.[62]

From 1927 to 1936 the National Library was housed in A Block at the north end of West Block, and occupied all levels (Figure 18). At the time, it was primarily a parliamentary library, rather than a national cultural institution.[63]

The ‘sparse and restricted services of the National Library’ were criticised in a 1934 report on libraries in Australia. [64] The following year, the Prime Minister’s Department provided supplementary funding to the library, and in 1936, the library relocated. Purpose-built premises for the National Library were completed, enabling the co-location of all collections and staff within one building in the Parliamentary Triangle.

Figure 17 Public servants in the Prime Minister's Department, West Block, 1928

Source: National Archives of Australia, NAA A3560 7557

Figure 18 Plans for the National Library at West Block, 1926

Source: National Archives of Australia, A2617 Section 14/1411

Major alterations to West Block were required to accommodate the new External Affairs Department and for the relocation of the Auditor-General’s department, which was to be moved to Canberra from Melbourne.[65]

Works undertaken in 1927-38 included:

- Enclosure of the corner balconies and verandas to create additional office space[66]