The Australian Maritime Safety Authority makes this heritage management plan under section 341S of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) for Cape Wickham Lighthouse.

20 May 2022

Mick Kinley

Chief Executive Officer

Copyright

© Australian Maritime Safety Authority

The Australian Maritime Safety Authority encourages the dissemination and exchange of information provided in this publication.

Except as otherwise specified, all material presented in this publication is provided under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. This excludes:

- the Commonwealth Coat of Arms

- this department's logo

- content supplied by third parties.

The Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The details of the version 4.0 of the licence are available on the Creative Commons website, as is the full legal code for that licence.

Third Party Copyright

Some material in this document, made available under the Creative Commons Licence framework, may be derived from material supplied by third parties. The Australian Maritime Safety Authority has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© [name of third party]’ or ‘Source: [name of third party]’. Permission may need to be obtained from third parties to re-use their material.

Acknowledgements

The Australian Maritime Safety Authority acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of country throughout Australia and their connections to land, sea and community.

Contact

For additional information or any enquiries about this heritage management plan, please contact:

The Australian Maritime Safety Authority,

Manager Asset Management and

Preparedness,

PO Box 10790,

Adelaide Street, Brisbane QLD 4000

Phone: (02) 6279 5000 (switchboard)

Email: Heritage@amsa.gov.au

Website: www.amsa.gov.au

Attribution

AMSA’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording:

Source: Australian Maritime Safety Authority Cape Wickham Lighthouse Heritage Management Plan – 2022

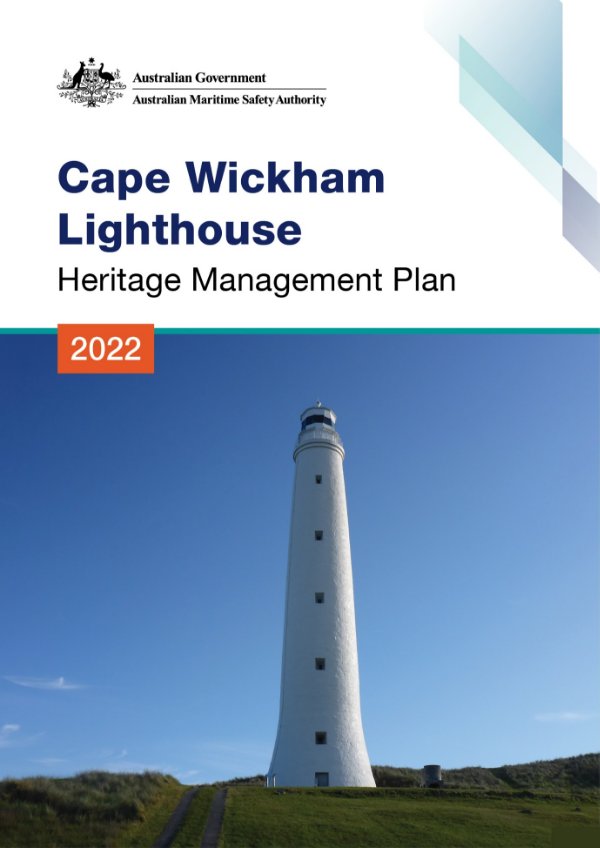

Front cover image

Figure 1. Cover photo of Cape Wickham lighthouse ( ©AMSA, 2018)

More information

For enquiries regarding copyright including requests to use material in a way that is beyond the scope of the terms of use that apply to it, please contact us through our website: www.amsa.gov.au

Cape Wickham Lighthouse

Heritage Management Plan

2022

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Background and purpose

- Heritage management plan objectives

- Methodology

- Status

- Authorship

- Acknowledgements

- Language

- Previous reports

- Sources of information and images

2. Cape Wickham Lightstation site

2.1 Location

2.2 Setting and landscape

2.3 Lease and ownership

2.4 Access

2.5 Listings

3. History

3.1 General history of lighthouses in Australia

3.2 Tasmanian Lighthouse Administration

3.3 King Island: a history

3.4 Building a lighthouse

3.5 Lighthouse keeping

3.6 Chronology of major events

3.7 Changes and conservation over time

3.8 Summary of current and former uses

3.9 Summary of past and present community associations

3.10 Unresolved questions or historical conflicts

3.11 Recommendations for further research

4. Fabric register

4.1 Register

4.2 Related object and associated AMSA artefact

4.3 Comparative analysis

5. Heritage significance

5.1 Commonwealth heritage listing – Cape Wickham Lighthouse

5.2 Tasmanian State heritage register – Cape Wickham Lighthouse

5.3 Condition and integrity of the Commonwealth heritage values

5.4 Gain/loss of heritage values

6. Opportunities and constraints

6.1 Implications arising from significance

6.2 Framework: sensitivity to change

6.3 Statutory and legislative requirements

6.4 Operational requirements

6.5 Occupier needs

6.6 Proposals for change

6.7 Potential pressures

6.8 Process for decision-making

7. Conservation management principles and policies

7.1 Policies

8. Policy implementation plan

8.1 Plan and schedule

8.2 Monitoring and reporting

9. Appendices

Appendix 1. Glossary of heritage conservation terms

Appendix 2. Glossary of historic lighthouse terms relevant to Cape Wickham

Appendix 3. Cape Wickham current light details

Appendix 4. Table demonstrating compliance with the EPBC Regulations

Reference list

Endnotes

List of Figures

Figure 1. Cover photo of Cape Wickham Lighthouse (© AMSA, 2018)

Figure 2. Planning process applied for heritage management (Source: ICOMOS Australia, 1999)

Figure 3. View of King Island within Bass Strait (Map data ©2021 Google, TerraMetrics)

Figure 4. View of King Island coastline from Cape Wickham Lighthouse tower (© AMSA, 2017)

Figure 5. Cape Wickham AMSA map of lease (Map data: Esri, DigitalGlobe, GeoEye, Earthstar Geographics, CNES/Airbus DS, USDA, USGS, AeroGRID, IGN, GIS User Community)

Figure 6. View of surrounding rural landscape from Cape Wickham Lighthouse tower (© AMSA, 2017)

Figure 7. Incandescent oil vapour lamp by Chance Brothers (Source: AMSA)

Figure 8. Dioptric lens on display at Narooma (Source: AMSA)

Figure 9. Dalén’s system – sun valve, mixer and flasher (Source: AMSA)

Figure 10. Blueprints for Cape Wickham lantern house, c.1861 Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A9568, 5/4/1 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

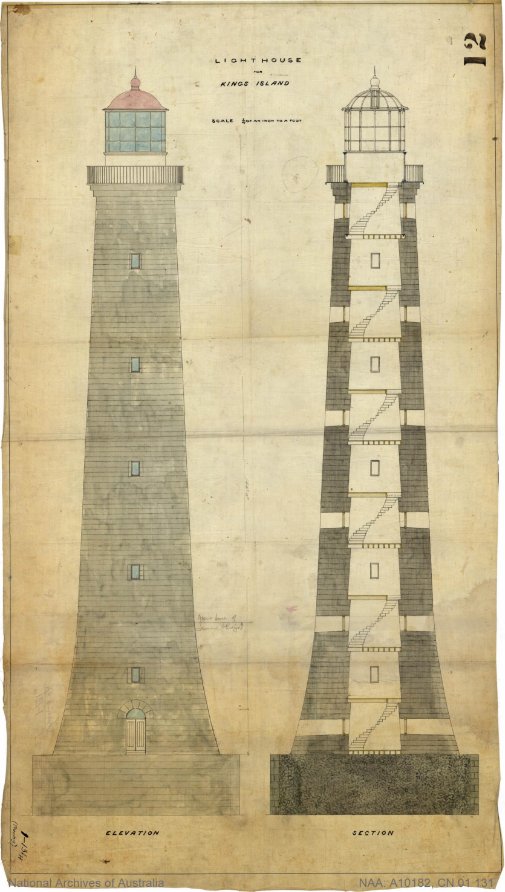

Figure 11. Blueprint of Cape Wickham Lighthouse tower, 1861. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A10182, CN 01 131 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Figure 12. Cape Wickham Lightstation prior to demolition of cottages, 1917. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A6247, B10/2. (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Figure 13. Design for Cape Wickham’s conversion to automatic operation, 1918. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A9568, 5/4/3 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Figure 14. Cape Wickham Lighthouse balcony replacement blueprints, 1918. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A10182, CN 01 133 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Figure 15. 150th anniversary opening, Cape Wickham Lighthouse (Source: AMSA, 2011)

Figure 16. From left to right: Swan Island Lighthouse (1845), Goose Island Lighthouse (1846), and Cape Wickham Lighthouse (1861) (Source: AMSA)

Executive summary

Cape Wickham Lighthouse is a historic site recognised by both Commonwealth and State Governments for its heritage significance. The lighthouse was placed on the Commonwealth Heritage List in 2004 for its contribution to the network of lighthouses established in Bass Strait in the 19th century. It is renowned as the tallest Australian lighthouse, for its aesthetic appeal in the rural landscape, and for the retention of its original Wilkins & Co lantern house and timber staircase.

Cape Wickham Lighthouse was placed on the Tasmanian heritage register for its historical, informative and aesthetic significance, in addition to its significant rarity and community associations.

Situated on the northern shore of King Island (Tas), the lighthouse overlooks Bass Strait, a treacherous stretch of water which separates the Australian State of Tasmania from the mainland. Built in 1861, the lighthouse was constructed to increase safety within Bass Strait following the boom of coastal shipping along the mainland’s south-east corner. The masonry tower was designed by Tasmanian-based engineer, WB Falconer, and the lightstation originally comprised of a tower, three keeper residences, and a superintendent’s house.

Although the Cape Wickham Lighthouse orignally housed a 1st Order Chance Bros catadioptric lens, the tower now exhibits a light-emitting diode (LED) source through a 1946 Chance Bros six panel catadioptric lens. The light now runs on an automated mechanism as part of AMSA’s network of Aids to Navigation (AtoN). The equipment is serviced by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority’s (AMSA) maintenance contractor who visits at least once each year. AMSA officers visit on an ad hoc basis for auditing, projects and community liaison purposes.

The larger part of the lightstation lies outside of the AMSA lease and is managed by Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service (TAS PWS). Although visitors are able to access the site, the light tower maintains restricted access.

This heritage management plan is concerned mainly with the lighthouse tower, but also addresses the management of the surrounding precinct and land. The plan is intended to guide decisions and actions. This plan has been prepared to integrate the heritage values of the lighthouse in accordance with the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act) and the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Regulations 2000 (Cth) (EPBC Regulations).

Well-built and generally well-maintained, Cape Wickham Lighthouse precinct is in relatively good, stable condition. The policies and management guidelines set out in this heritage management plan strive to ensure that the Commonwealth heritage values of the Cape Wickham Lighthouse are recognised, maintained, and preserved for future generations.

- Introduction

1.1 Background and purpose

The Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) is the Commonwealth agency responsible for coastal AtoN. AMSA’s network includes Cape Wickham Lighthouse built in 1861.

- a description of the place, its heritage values, their condition and the method used to assess its significance

- an administrative management framework

- a description of any proposals for change

- an array of conservation policies that protect and manage the place

- an implementation plan

- ways the policies will be monitored and how the management plan will be reviewed.

AMSA has prepared this heritage management plan to guide the future conservation of the place. This plan provides the framework and basis for the conservation and best practice management of Cape Wickham Lighthouse in recognition of its heritage values. The policies in this plan indicate the objectives for identification, protection, conservation and presentation of the Commonwealth heritage values of the place. Figure 2 shows the basic planning process applied.

Figure 2. Planning process applied for heritage management (Source: Australia ICOMOS, 1999)

1.2 Heritage management plan objectives

The objectives of this heritage management plan are to:

- protect, conserve and manage the Commonwealth heritage values of Cape Wickham Lighthouse

- interpret and promote the Commonwealth heritage values of Cape Wickham Lighthouse

- manage use of the lighthouse

- use best practice standards, including ongoing technical and community input, and apply best available knowledge and expertise when considering actions likely to have a substantial impact on Commonwealth heritage values.

In undertaking these objectives, this plan aims to:

- Provide for the protection and conservation of the heritage values of the place while minimising any impacts on the environment by applying the relevant environmental management requirements in a manner consistent with Commonwealth heritage management principles.

- Take into account the significance of King Island as a cultural landscape to Aboriginal people over many thousands of years.

- Recognise that the site has been occupied by lease holders since the early 20th century.

- Encourage site use compatible with the historical fabric, infrastructure and general environment.

- Record and document maintenance works, and changes to the fabric, in the Cape Wickham Lighthouse fabric register (see 4.1 Fabric).

The organisational planning cycle and associated budgeting process is used to confirm requirements, allocate funding and manage delivery of maintenance activities. Detailed planning for the AtoN network is managed through AMSA’s internal planning processes.

An interactive map showing many of AMSA’s heritage sites, including Cape Wickham Lighthouse, can be found on AMSA’s Interactive Lighthouse Map[1].

1.3 Methodology

- details a history of the site based on information sourced from archival research, expert knowledge, and documentary resources,

- provides a description of the site based on information sourced from site inspection reports and fabric registers, and;

- details the Commonwealth heritage criteria satisfied by Cape Wickham Lighthouse as set out by schedule 7A of the EPBC Regulations.

The criterion set out at Schedule 7A (h) (i-xiii) informed the development of the required policies for the management of Cape Wickham Lighthouse, in conjunction with input from the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment on best practice management.

Consultation

AMSA also consulted with Aboriginal Heritage Tasmania (Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, Tas) and were provided with information on Aboriginal heritage in the vicinity of the lighthouse. This information was included in the plan.

In preparation of the plan, AMSA consulted with TAS PWS who provided valuable information and feedback on land management. This information was included within the plan.

The draft management plan was advertised in accordance with the EPBC Act and the EPBC Regulations. On the 22 December 2021 a notice was placed in The Australian newspaper publication which invited the general public to review the draft plan and provide feedback. Public consultation closed on the 20 January 2022. No submissions were received from the general public.

AMSA submitted the draft plan to the Heritage Branch of the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment who provided feedback on the draft. These comments were incorporated into the final document. A developed draft was submitted to the Federal Minister through the Heritage Branch and in that process the Minister’s delegate sought advice from the Australian Heritage Council. On 14 April 2022, the Minister’s delegate determined that the plan satisfied the requirements of the EPBC Act.

1.4 Status

1.5 Authorship

This plan has been prepared by AMSA. At the initial time of publication, Australian Maritime Systems Group (AMSG) is the contract maintenance provider for the Commonwealth Government’s AtoN network including Cape Wickham Lighthouse.

1.6 Acknowledgements

1.7 Language

For clarity and consistency, some words in this plan such as restoration, reconstruction and preservation, are used with the meanings defined in the Illustrated Burra Charter[2]. See Appendix 1 ‘Glossary of heritage conservation terms’. Also see Appendix 2 ‘Glossary of lighthouse

terminology’ which sets out the technical terminology used in this plan.

1.8 Previous reports

A Heritage Site Report was produced by the Australian Construction Services – Heritage and Environment Group, for AMSA in September 1993.[3]

A Heritage Lighthouse Report was produced by heritage architect consultant, Peter Marquis-Kyle, for AMSA in 2007.[4]

1.9 Sources of information and images

2. Cape Wickham Lightstation site

2.1 Location

The Cape Wickham Lighthouse is located on King Island, a 1,098 kilometre-squared island found within Bass Strait nestled between the Australian state of Tasmania and the mainland. Situated approximately nine kilometres north-north-west of Egg Lagoon, Cape Wickham Lighthouse stands on the northern tip of the Island.

Coordinates: 39º 35.3060’S, 143º 56.5830’E.

Figure 3. View of King Island within Bass Strait (Map data: ©2021 Google, TerraMetrics)

Figure 3. View of King Island within Bass Strait (Map data: ©2021 Google, TerraMetrics)

2.2 Setting and landscape

As the second largest island in the Bass Strait, King Island is a predominantly rural land mass subject to the Roaring Forties, strong westerly winds found across the southern hemisphere. With a relatively flat topography, the island features a combination of sand dunes along the western coastline, and steep rocky cliffs along the eastern and southern coastline.

The Cape Wickham Lighthouse, situated along the northern point of King Island, is surrounded by open, rural plains and a golf course. The tower is located within Cape Wickham State Reserve which is managed by the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service.

Figure 4. View of coastline from Cape Wickham lighthouse tower (© AMSA, 2017)

Fauna and flora

King Island maintains a range of fauna and flora, somewhat limited by the island’s geographic isolation. With an estimated 28 native vegetation communities, six communities are listed as ‘threatened’. These include:

- coastal complex

- Eucalyptus brookeriana

- Eucalyptus globulus

- Melaleuca ericifolia

- seabird rockery complex

- wetlands

Fifty flora species on the island have been registered and include:

- Hedycarya angustifolia (Australian mulberry)

- Elaeocarpus reticulatus (blueberry ash)

- Pimelea axiflora (bootlace bush)

The island maintains a diverse range of fauna including:

- six fish species

- six frog species

- nine reptile species

- 164 bird species

- 12 mammal species

Due to the strong bird population, specific areas have been identified on the Island as Important Bird Areas. The Lavinia State Reserve located to the north-east is recognised as a habitat for the critically endangered orange-bellied parrot (Neophema chrysogaster) along their migration route.

A biodiversity management plan for King Island was implemented in 2012. This plan can be accessed publicly via the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment website.[5]

2.3 Lease and ownership

AMSA holds a lease for the lighthouse and land from the Minister administering the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1970 (Tas). The lease is currently administered through TAS PWS.

The AMSA lease consists of two parcels of land:

- lot 1 (1964 metres-squared)

- lot 2: lighthouse tower (780 metres-squared)

The current lease was signed on 1 May 1998 for a period of 25 years, with the option to renew for a period of 25 years.

Figure 5. Cape Wickham AMSA map of lease (Map data: Esri, DigitalGlobe, GeoEye, Earthstar Geographics, CNES/Airbus DS, USDA, USGS, AeroGRID, IGN, GIS User Community)

2.4 Access

Cape Wickham Lighthouse can be accessed by vehicle via Cape Wickham Road with open pedestrian access available from all directions of the lighthouse tower. Access inside the lighthouse is restricted to authorised personnel only.

Figure 6. View of surrounding rural landscape from Cape Wickham lighthouse tower (© AMSA, 2011)

2.5 Listings

Cape Wickham Lighthouse is listed on the following heritage registers:

Register | Place ID |

Commonwealth Heritage List | 105567[6]

|

Tasmanian Heritage Register | 3613[7]

|

Register of the National Estate (non-statutory archive) | 102874[8]

|

3. History

3.1 General history of lighthouses in Australia

The following century oversaw the construction of hundreds of lighthouses around the country. Constructing and maintaining a lighthouse were costly ventures that often required the financial support of multiple colonies. However, they were deemed necessary aids in assisting the safety of mariners at sea. Lighthouses were firstly managed by the colony they lay within, with each colony developing their own style of lighthouse and operational system. Following Federation in 1901, which saw the various colonies unite under one Commonwealth government, lighthouse management was transferred from state hands to the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service.

Lamps and optics: an overview

Lighthouse technology has altered drastically over the centuries. Eighteenth century lighthouses were lit using parabolic mirrors and oil lamps. Documentation of early examples of parabolic mirrors in the United Kingdom, circa 1760, were documented as consisting of wood and lined with pieces of looking glass or plates of tin. As described by Searle, ’When light hits a shiny surface, it is reflected at an angle equal to that at which it hit. With a light source is placed in the focal point of a parabolic reflector, the light rays are reflected parallel to one another, producing a concentrated beam’. [9]

Figure 7. Incandescent oil vapour lamp by Chance Brothers (Source: AMSA)

Figure 8. Dioptric lens on display at Narooma (Source: AMSA)

Figure 8. Dioptric lens on display at Narooma (Source: AMSA)

Early Australian lighthouses were originally fuelled by whale oil and burned in Argand lamps, and multiple wicks were required in order to create a large flame that could be observed from sea. By the 1850s, whale oil had been replaced by colza oil, which was in turn replaced by kerosene, a mineral oil.

In 1900, incandescent burners were introduced. This saw the burning of fuel inside an incandescent mantle, which produced a brighter light with less fuel within a smaller volume. Light keepers were required to maintain pressure to the burner by manually pumping a handle as can be seen in Figure 7.

In 1912, Swedish engineer Gustaf Dalén, was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for a series of inventions relating to acetylene-powered navigation lights. Dalén’s system included the sun valve, the mixer, the flasher, and the cylinder containing compressed acetylene. Due to their efficiency and reliability, Dalén’s inventions led to the gradual demanning of lighthouses. Acetylene was quickly adopted by the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service from 1915 onwards.

Large dioptric lenses, such as that shown in Figure 9, gradually decreased in popularity due to cost and the move towards de-staffed automatic lighthouses. By the early 1900s, Australia had stopped ordering these lenses with the last installed at Eclipse Island in Western Australia in 1927. Smaller Fresnel lenses continued to be produced and installed until the 1970s when plastic lanterns, still utilising Fresnel’s technology, were favoured instead. Acetylene remained in use until it was finally phased out in the 1990s.

In the current day, Australian lighthouses are lit and extinguished automatically using mains power, diesel generators, and solar-voltaic systems.

Figure 9. Dalén's system - sunvalve, mixer, and flasher (Source: AMSA)

The Commonwealth Lighthouse Service

When the Australian colonies federated in 1901, they decided the new Commonwealth Government would be responsible for coastal lighthouses. This included major lights used by vessels travelling from port to port, not the minor lights used for navigation within harbours and rivers. There was a delay before this new arrangement came into effect and existing lights continued to be operated by the states.

Since 1915, various Commonwealth departments have managed lighthouses. AMSA, established under the Australian Maritime Safety Authority Act 1990 (Cth), is now responsible for operating Commonwealth lighthouses and other aids to navigation, along with its other functions.

3.2 Tasmanian Lighthouse Administration

The table below outlines the timeline for Tasmanian lighthouse management.

Time Period | Administration |

1915 – 1927

1927 – 1963

1963 – 1972

1972 – 1982

1982 – 1983

1983 – 1985

1985 – 1987

1987 – 1990

1991 --

| Lighthouse District No 3. (Victoria, New South Wales, Tasmania), Hobart Headquarters.

Deputy Director of Lighthouses and Navigation, Tasmania.

Department of Shipping and Transport, Regional Controller, Tasmania.

Department of Transport [III], Regional Controller, Tasmania.

Department of Transport and Construction. Victoria-Tasmania Region, Transport Division (Tasmania)

Department of Transport [IV] Victoria-Tasmania Region, Hobart Office.

Department of Transport [IV], Tasmanian Region.

Department of Transport and Communications, Tasmanian Region.

Australian Maritime Safety Authority.

|

3.3 King Island: a history

Aboriginal history

The Office of Aboriginal Affairs (Tas) advised that although Aboriginal people did visit King Island, there was no permanent inhabitation of the island. Numerous Aboriginal heritage sites were recorded in the Victoria Cove area and around Lake Wickham on the island.

Further information from the Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania will be included in this section in future updates of the plan.

Early European history

In 1798, the passage of water separating Tasmania from the mainland was charted by British explorer George Bass, and British navigator and cartographer Matthew Flinders. Named ‘Bass Strait’, this passage was traversed by countless ships that had previously been forced to journey around the south coast of Tasmania. However, the maps of the Strait Flinders created and sent back to England in 1800 did not include King Island. In 1799, Captain Reed sighted King Island while on a seal hunting expedition aboard the schooner Martha. Reed informed Flinders of the Island’s existence and in Flinders’ second map of the Strait made mention of a “Land of considerable extent”.[10]

Following Reed’s sighting, British Privateer, Captain John Black, visited the island and named the island after New South Wales governor Phillip Gidley King. In that same trip, Black named Harbinger Rocks, located off the island’s north-west coast, after his ship Harbinger. It was here that an abundance of fur seals and Southern elephant seals were found – the seals were exploited into extinction shortly thereafter.[11]

Governor King, concerned the French navigator Nicolas Baudin was en route to claim the island for France, ordered the ship Cumberland to sail from Sydney in 1800 and claim the land for Britain. Despite failing to claim the land for France, Baudin circumnavigated and mapped the island in 1802.[12]

Hunting remained the primary practice on the island throughout the early 19th century. By 1854, the island had emptied of inhabitants save for the occasional visitors who scoured the land for any remaining seals and wallabies. In 1859, a communications cable was erected across the Bass Strait connecting King Island to Cape Otway in Victoria, and Stanley Head on the Tasmanian mainland.

By the 1880s, the land on King Island was officially opened for grazing and the township of Currie, located along the west coast, developed shortly thereafter.

3.4 Building a lighthouse

Why Cape Wickham?

The Bass Strait passage was notorious for the number of lives lost in its waters following European settlement in the region. An estimated 60 vessels and over 600 lives were claimed within the passage, significantly from the wrecks of the Neva in 1835 and the Cataraque in 1845.[13]

In 1841, the first recommendation for the lighting of the Bass Strait was made by the governor of Van Diemen’s Land, John Franklin. Franklin initially proposed the erection of a lighthouse on the northern coast of King Island and, in 1846, a Select Committee on Light Houses supported this recommendation. The following year however, King Island as a site was dismissed as some voiced concerns that a light on King Island would draw vessels onto Harbinger Reefs – a submerged collection of reefs located several miles west of the Island. Instead, favour was diverted to the construction of a light at Cape Otway along the Victorian coastline.[14]

Despite the construction of a new light on Cape Otway, Bass Strait continued to claim lives over the following years. Between the years of 1854 and 1856, no less than six ships were lost in the waters around King Island – occurrences that propelled plans for a Cape Wickham Lighthouse to the forefront. At the Joint Colonial Lighthouse Conference of 1856, it was decided that a lighthouse would be constructed on Cape Wickham, and that it would be built and maintained by Tasmania, Victoria and New South Wales.[15]

Design

Tasmanian-based engineer W B Falconer was chosen to design the light for Cape Wickham. Upon attempting to visit the Island in 1858 for a site inspection, the whaleboat carrying Falconer overturned and a fellow traveller was drowned. Falconer managed to pull himself to safety and went on to inspect the proposed lighthouse site.[16]

Following this visit, Falconer produced two differing tower designs – one masonry tower at an estimated cost of £19,507, and a pre-fabricated cast iron tower at an estimated cost of £23,743. The masonry tower design was eventually chosen for the site.[17]

In order for the light to be visible in an arc from south-south-west to east-south-east at a distance of 37 kilometres, it was reccomended that the tower be 100 metres above high water mark. Owing to the selected Cape Wickham site being a ridge 52 metres above sea level, it was calculated that the tower needed to be 48 metres in height.[18]

Construction and equipment when built

Following the acceptance of a design, tenders for the construction of Cape Wickham Lighthouse were called in November 1859. The successful contractors were Kirkland and Co. of Melbourne, and construction started shortly thereafter.[19]

By 1860, two thousand tons of granite had been quarried on King Island and transported via tramway to the chosen site. By October of the same year, the foundations for the tower had been laid. The masonry tower was complete by 4 June 1861, and the lantern and apparatus arrived on King Island shortly thereafter.

Following its completion in 1861, the Cape Wickham Lighthouse stood at 158 feet (48 metres) with 11 flights of wooden stairs. The lantern room housed a large Wilkins and Co. single-wick

lamp which shone through a 1st Order Chance Bros. catadioptric lens and powered by sperm whale oil (intensity: 7,500 candlepower). The tower, which came to a final cost of £18,281, was also accompanied by three keeper residences and a superintendent’s house (these buildings were later demolished circa. 1921).[20] The light was first exhibited on 1 November 1861, however the lighthouse was never officially opened.

Figure 10. Blueprints for Cape Wickham lantern house, c. 1861 Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A9568, 5/4/1 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Figure 11. Blueprint of Cape Wickham Lighthouse tower, 1861. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A10182, CN 01 131 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

3.5 Lighthouse keeping

Presided over by a superintendent and three assistants, the Cape Wickham Lighthouse was staffed from its construction in 1861 until 1921. Captain Duigan was the first superintendent stationed at the light, followed by Edward Nash Spong in 1862 who was stationed at Cape Wickham for 30 years.

With open settlement on the island strictly forbidden until the 1880s, life at the Cape Wickham Lightstation was increasingly isolated. Fishermen and sealers were the mere few that visited the island albeit irregularly. It wasn’t until the construction of a light at Currie (1879) on the west coast of the island that a permanent population was established.[21]

Following the installation of an automatic acetylene flasher, the need for a superintendent and assistants onsite was no longer necessary, and the cottages were demolished in 1921.[22]

3.6 Chronology of major events

Listed below are the major events related to the Cape Wickham Lighthouse.

Date | Event |

1 Nov 1861 | Light first exhibited from Cape Wickham Lighthouse.

|

Circa 1880s | King Island opened for settlement (farming and grazing). The township of Currie is established.

|

17 May 1898 | Lighthouse struck by lightning – ground floor of tower ‘pierced’ by strike. Assistant lightkeeper shocked and knocked unconscious.[23]

|

13 July 1918-1921 | Lighthouse converted to automated operation and de-staffed. Original balcony replaced and keepers’ cottages demolished.[24]

|

1939-1941 | Radio beacon established at Cape Wickham.[25]

|

1965 | New generator room built.

|

1988-1989 | Radio beacon discontinued.

|

Nov 2011 | Lighthouse ‘officially’ opened by former Governor-General Quentin Bryce.

|

Figure 12. Cape Wickham Lightstation prior to demolition of cottages, 1917. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A6247, B10/2 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

3.7 Changes and conservation over time

Owing to alterations in lighthouse fabric and technology over the course of the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries, Cape Wickham Lighthouse has undergone a number of changes.

The Brewis Report

Commander CRW Brewis, retired naval surveyor was commissioned in 1911 by the Commonwealth Government to report on the condition of existing lights and to recommend any additional ones. Brewis visited every lighthouse in Australia between June and December 1912 and produced a series of reports published in their final form in March 1913. These reports were the basis for future decisions made in relation to the towers’ capabilities.[26]

The recommendations made for the Cape Wickham Light included:

- discontinuing the signal station

- changing the light’s character from fixed to occulting

- installing an 85mm incandescent mantle, and increasing the light’s power to 35,000 candlepower.

Cape Wickham (King Island). (22 miles from Currie Harbour, by road.) Lat. 39º 36’ S., Long. 143º 57’ E., Chart No. 404.- Established in the year 1861. Lloyd’s Signal Station. Not connected by telephone. Character.- One white, fixed apparatus, 1st Order, dioptric. Candle-power, 7500. Granite tower, 145 feet. Height of focal plane, 280 feet above high water. Visible, in clear weather, 24 nautical miles, from N. 22º E., through east, to N. 76º W. Condition and State of Efficiency.- The light is situated 22 miles by road from Currie Harbour, the township of King Island. There are farms near the light-house so the position is not isolated. The light-house, tower, and apparatus are in a good state of preservation. The dwellings require repairs, and renewals to fences are necessary. Three light-keepers are stationed here. RECOMMENDED.- (a) As reefs extend for a distance of 4 ½ miles to seaward, the tides being very treacherous, setting strongly towards King Island, the Signal Station be discontinued. Vessels should give this locality a wide berth and not be encouraged to approach within signalling distance. Caution.- Extract from the Admiralty Sailing Directions, Australia, Vol. I., page 410, referring to the Report by the Light-house Commissioners appointed by the State Government in the year 1859:- “In advising the erection of a light-house in the neighbourhood of Cape Wickham, the Commissioners wish to guard themselves from affording the public any reasonable supposition that this light can be at all considered in a position of a great highway light for the navigation of Bass Strait; and the light at Cape Wickham can only be regarded as a beacon warning navigators of danger, rather than a leading light to a great thoroughfare.” (b) The light be given a distinctive character, by inserting an occulting screen, actuated by clockwork mechanisms (to be wound every sixteen hours), thus converting the light from fixed to occulting. Light characteristic – occulting every five seconds; light, two and a-half seconds; eclipse, two and a-half seconds. Present tower and optic to be used. (c) The power of the light be increased from 7,500 to 35,000 c.p., and economy effected in the consumption of oil by installing an 85 mm incandescent mantle; illuminant, vaporised kerosene.

|

- Brewis Report, 1912

Alterations to the light

Listed below is the chronology of alterations to the Cape Wickham Lighthouse lens and light source.

Date | Alterations |

1889 | Four-wick Trinity burner installed.

|

5 July 1918 | Lighthouse converted to automatic operation. Original single-wick lamp replaced by an acetylene lamp. Intensity 13,000 cp. (See Figure 15 for the 1918 light conversion design)

|

12 Feb 1946 | Original lens replaced by Chance Bros. 250mm double flashing lens (one revolution every 30 seconds). Converted to diesel electric operation: 110 V, 500 W Lamp Intensity 170,000 cp. |

1980 | Converted to mains electric operation with diesel backup |

2012 | Diesel Generator removed, UPS back up power supply installed |

2016 | Existing lampchanger replaced by LED light source |

Figure 13. Design for Cape Wickham's conversion to automatic operation, 1918. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A9568, 5/4/3 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Conservation works

The following table lists the rectification works undertaken to maintain the lighthouse.

Date | Works completed

|

2019 | Lead paint removal (external and internal surfaces). Major tower repaint (external and internal surfaces). Asbestos removal from lantern room. |

Figure 14. Cape Wickham Lighthouse balcony replacement blueprints, 1918 Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A10182, CN 01 133 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

3.8 Summary of current and former uses

Since construction in 1861, Cape Wickham Lighthouse has been used as a marine AtoN for mariners at sea. Its AtoN capabilities remain its primary use.

3.9 Summary of past and present community associations

The Cape Wickham Lighthouse is firmly embedded within the King Island community.

Aboriginal associations

Further consultation is required with traditional stakeholders will be undertaken for a greater understanding of the past and present associations held across the region. This section will be updated following these consultations.

Local, national and international associations

As the tallest Australian lighthouse, Cape Wickham is significant within the King Island community and surrounding areas. Owing to its unique history – resulting in the lighthouse never having an official ‘opening’ – the surrounding community held a 150th anniversary opening in November 2011. It was at this event that the lighthouse, along with the memory of those lost in the surrounding waters, was marked by former governor-general, Quentin Bryce, who officially opened Cape Wickham Lighthouse.[27]

3.10 Unresolved questions and historical conflicts

Minor dates concerning the lighthouse’s history are disputed between differing historical resources. While the date of the lighthouse’s automation is widely corroborated as 1918, it is disputed how quickly afterwards the lighthouse was de-staffed and the keepers’ cottages demolished. Various sources distinguish the lighthouse was de-staffed immediately, however some claim it was not until 1921, the same year as the demolition of the cottages.

Depending on the historical sources accessed, the radio beacon was installed between 1939-1941, and removed between 1988-1989.

3.11 Recommendations for further research

Further investigation is required to determine the correct chronology of events concerning alterations carried out at the lighthouse. Additionally, investigation on those stationed at the lighthouse would provide further information on the historical and cultural significance of Cape Wickham Lighthouse.

Figure 15. 150th Anniversary Opening Cape Wickham Lighthouse (Source: AMSA, 2011)

4. Fabric register

4.1 Register

The cultural significance of the lighthouse resides in its fabric, and in its intangible aspects – such as the meanings people ascribe to it, and its connections to other places and things. The survival of its cultural value depends on a well-informed understanding of what is significant, and on clear thinking about the consequences of change. The Burra Charter sets out good practice for conserving cultural significance.

(All images in sub-sections 4.1 and 4.2 – © AMSA)

Lighthouse feature: Lantern roof

Description and condition

12-sided pyramidal roof of copper sheets lapped and screwed to ribs. Each face has three sheets – the lower sheet is folded up at the joint, and the upper sheet is folded down.

- Ribs – straight, radial ribs

- Inner skin – none

- Ventilator – ball type, with wind vane attached

- Lightning conductor – vertical pole on roof, with three spikes at top, and two braces to roof, eight vertical spikes attached near the gutter

- Gutter – polygonal fabricated gutter attached to ring of metal pieces bolted together.

- Handrails – none

- Ladder rail – discontinuous, attached to gutter

- Curtain rail – attached to ribs with brackets

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification Works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The lantern roof is an essential part of the lighthouse – exhibiting a style of lighthouse built throughout the 1860s (criterion a, criterion d)

The lantern roof contributes to the aesthetic value of the lighthouse (criterion e)

Lighthouse feature: Lantern glazing

© AMSA, 2020

Description and condition

1861 Wilkins & Co.

- Panes – flat trapezoidal glass, three tiers. Upper tier, and some panes of the lower tier, painted out.

- Astragals – vertical and horizontal astragals of lamb’s tongue section, bolted to roof ring at top, and to lantern base below.

- Handholds – one on each vertical astragal, fixed to cover strips.

Finish | astragals and glazing strips painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service reglaze as necessary prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification Works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The lantern glazing is both an original and essential part of a historic lighthouse – exhibiting a design of lighthouses built throughout the 1860s (criterion a, criterion d)

The lantern glazing contributes to the aesthetic value of the lighthouse (criterion e)

Lighthouse feature: Internal catwalk

© AMSA, 2020

Description and condition

1861 Wilkins & Co cast iron lattice floor panels supported on cast iron brackets bolted to the lantern base. The brackets also support a circular cast iron lattice platform.

- Ladder – fixed winding stair with cast iron treads cantilevered from a central iron post. Wrought iron handrail on cast iron balusters.

- Aluminium grating – recent aluminium grating installed to span the gap between the catwalk panels and the platform as a safety measure for service personnel. Grating supported on both the catwalk brackets and an aluminium angle.

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | recent aluminium grating: low other parts: high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification Works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The internal catwalk is both an original and essential part of a historic lighthouse (criterion a).

Lighthouse feature: External catwalk

© AMSA, 2020

Description and condition

1861 Wilkins & Co cast iron lattice floor panels supported on pierced cast iron brackets bolted to the lantern base.

One floor panel has been removed and brackets on either side of the opening formed have been modified.

- Handrail – None.

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification Works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The external catwalk is both an original and essential part of a historic lighthouse – exhibiting a design of lighthouses built throughout the 1860s (criterion a, criterion d).

The external catwalk contributes to the aesthetic value of the lighthouse (criterion e).

Lighthouse feature: Lantern base

© AMSA, 2020

Description and condition

1861 Wilkins & Co, irregular 12-sided polygonal prism in form, with alternating long and short faces. Panels of cast iron bolted together with flanged joints. Decorative corrugated relief pattern on outside.

- Internal lining – corrugated iron of fine pitch.

- Vents – external vents sealed. Internal circular openings below the internal catwalk.

- Door – fibreglass door hung on double-knuckle hinges and secured with two strong-backs with hand wheels. The door closes against rubber seals.

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification Works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The lantern base is both an essential and original part of a historic lighthouse – exhibiting one particular design of lighthouses built throughout the 1860s (criterion a, criterion d).

Lighthouse feature: Lantern floor

© AMSA, 2020

Description and condition

Timber floor of pit-sawn boards supported on pit-sawn joists built into the tower walls, with overlay of wide machine-sawn boards. Lines of tack marks indicate a previous overlay of linoleum.

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification Works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The lantern floor is both an early and essential part of a historic lighthouse – exhibiting one particular design of lighthouses built throughout the 1860s (criterion a, criterion d).

Lighthouse feature: Lens assembly

© AMSA, 2020

Description and condition

1946 Chance Bros six panel catadioptric lens assembly of 250mm focal radius in gunmetal frame. Fitted with rotating frame with suspended cloth masks to stop parasitic flashes.

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | moderate |

Maintenance | keep in service clean at normal intervals |

Rectification Works | none |

Heritage significance: Moderate

The lens assembly is both an early and essential part of a historic lighthouse (criterion a).

The lens assembly contributes to the aesthetic values of the lighthouse (criterion e).

Lighthouse feature: Pedestal

© AMSA, 2020

© AMSA, 2020

Description and condition

1918 cast iron pedestal mounted on the 1861 platform, with 1988 twin motor-gearbox electric drive fixed on top.

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | moderate |

Maintenance | prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification Works | none |

Heritage significance: Moderate

The pedestal is both an early and essential part of a historic lighthouse (criterion a).

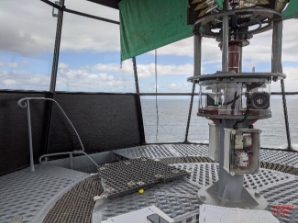

Lighthouse feature: Light source

© AMSA, 2020

© AMSA, 2020

Description and condition

Sealite SL-LED-324-W; 12 sided- 36LED light source mounted on existing pillar.

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | low |

Maintenance | none |

Rectification Works | none |

Heritage significance: Low

Lighthouse feature: Balcony floor

© AMSA, 2020

Description and condition

1918 concrete on top of the 1861 stone cornice. This floor replaced the original wider floor of cast iron.

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | moderate |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification Works | none |

Heritage significance: Moderate

The balcony floor is both an early and essential part of a historic lighthouse (with the 1861 stone cornice being an original feature) (criterion a).

The balcony floor contributes to the aesthetic value of the lighthouse (criterion e).

Lighthouse feature: Balcony balustrade

© AMSA, 2020

© AMSA, 2020

Description and condition

1918 iron balustrade with cast stanchions bolted to balcony floor. Top and bottom rails of round section.

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification Works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The balcony balustrade is both an early and essential part of a historic lighthouse (criterion a).

The balcony balustrade contributes to the aesthetic value of the lighthouse (criterion e).

Lighthouse feature: Walls

© AMSA, 2020

Description and condition

1861 walls of tooled stone blocks.

Finish | exterior: painted interior: bare stone |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals monitor condition of pointing and stonework |

Rectification Works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The walls are both an essential and original part of a historic lighthouse – its coursed stonework exhibiting one particular style of lighhtouses built throughout the 1860s (criterion a, criterion d).

The walls contriute to the rarity of the tower’s height (criterion b).

The walls contribute to the aesthetic value of the lighthouse (criterion e).

Lighthouse feature: Windows

© AMSA, 2020

Description and condition

Fixed glazing in timber window sashes in timber frames.

Finish | frames and sashes: painted glass: clear |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | window openings: high frames and glazing: low |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification Works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The window openings are an original and essential part of a historic lighthouse – exhibiting a style of lighthouses built throughout the 1860s (criterion a, criterion d).

The window openings contribute to the aesthetic value of the lighthouse (criterion e).

Lighthouse feature: Ground floor door

© AMSA, 2020

Description and condition

Recent timber framed and sheeted door, faced with stainless steel, hung in timber frame with iron semi-circular frame above.

Finish | outside of door: bare metal other parts: painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | moderate |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification Works | none |

Heritage significance: Moderate

The ground floor door is an essential part of a historic lighthouse with some historic features (i.e. timber frame) (criterion a).

Lighthouse feature: Intermediate floors

© AMSA, 2020

Description and condition

Ten 1861 intermediate timber floors (with later full or partial replacements), with machine-sawn joists and floorboards.

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification Works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The intermediate floors are both an original and essential parts of a historic lighthouse (criterion a).

The timber intermediate floors are a feature unique to the lighthouse (criterion b).

The intermediate floors contribute to the aesthetic value of the lighthouse (criterion e).

Lighthouse feature: Stairs

© AMSA, 2020

Description and condition

1861 geometric stair with timber treads on recent stainless steel stringers and fasteners.

- Balustrade – 1861 curved timber handrail and timber balusters.

Finish | painted |

Condition | some corrosion evident, otherwise intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service, prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification Works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The timber stairs are both an essential and original part of a historic lighthouse (criterion a).

The timber stairs are a feature unique to the lighthouse (criterion b).

The timber stairs contribute to the aesthetic value of the lighthouse (criterion e).

Lighthouse feature: Ground floor

© AMSA, 2020

Description and condition

1861 stone floor with concrete topping.

- Equipment – UPS back up power supply in two separate cabinets.

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint floor at normal intervals |

Rectification Works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The ground floor is both an original and essential part of a historic lighthouse – exhibiting one style of lighthouses built throughout the 1860s (criterion a, criterion d).

4.2 Related object and associated AMSA artefact

The artefacts listed below are recognised as being of heritage significance to Cape Wickham and registered within AMSA’s artefact catalogue.

© AMSA, 2020

© AMSA, 2020

Artefact | 150th Anniversary plaque

|

Maximo ID:

Location in lighthouse:

Condition:

| AR0287

Mounted inside lantern room

Good |

4.3 Comparative analysis

Cape Wickham Lighthouse is comprised of features that share similarities with other Tasmanian lighthouses. The 13’ 0” W Wilkins & Co lantern demonstrated a design similar to the 12’ 6” Wilkin & Co lantern installed in Swan Island Lighthouse (first lit 1845), and the Wilkins & Co lantern installed in Goose Island Lighthouse (first lit 1846). All three Tasmanian lighthouses are located offshore from the Tasmanian mainland, and both Cape Wickham and Goose Island lighthouses underwent similar alterations to their fabric in 1918. For example, the installation of iron balustrade with cast stanchions along the balconies.

Despite variations in design and fabric, Swan Island, Goose Island and Cape Wickham lighthouses are indicative of the typical stone lighthouse favoured for construction along Bass Strait throughout the mid-19th century.

Figure 16. From left to right: Swan Island Lighthouse (1845), Goose Island Lighthouse (1846), and Cape Wickham Lighthouse (1861) (Source: AMSA)

5. Heritage significance

5.1 Commonwealth heritage listing – Cape Wickham Lighthouse

The statement of significance and heritage value criteria listed below are directly taken from the Commonwealth heritage listing for the Cape Wickham Lighthouse (Place ID: 105567).

Commonwealth heritage statement of significance

The Cape Wickham Lighthouse, built 1861, is significant as an integral part of Bass Strait’s mid-nineteenth century network of lighthouses. This system represents the first example of cooperation by the Australian colonies in sharing the costs and responsibilities of providing navigational aids. (Criterion A.4) (Australian Historic Themes 3.8.1 Shipping to and from Australian ports; 3.8.2 Safeguarding Australian products for long journeys and 3.16.1 Dealing with hazards and disasters)

The Cape Wickham Lighthouse makes a dramatic contribution to the rural landscape of the northern tip of King Island. (Criterion E.1)

The Cape Wickham Lighthouse is a good example of a lighthouse built during the 1860s. It is forty eight metres high, which makes it the tallest lighthouse in Australia. It retains the original H Wilkins and Company lantern house and the original timber staircase, a feature that is not common in a stone lighthouse. (Criterion B.2 and D.2)

Commonwealth heritage values criteria

There are nine criteria for inclusion in the Commonwealth Heritage List – meeting any one of these is sufficient for listing a place. These criteria are similar to those used in other Commonwealth, state and local heritage legislation, although thresholds differ. In the following sections, the criteria met by Cape Wickham Lighthouse is discussed as based on the current Commonwealth Heritage Listing (Place ID 105567).

Criterion | Relevant attributes identified | Explanation |

Criterion A – Processes

This criterion is satisfied by places that have significant heritage value because of [their] importance in the course, or pattern, of Australia’s natural or cultural history.

|

| The Cape Wickham Lighthouse, built in 1861, is significant as an integral part of Bass Strait’s mid-nineteenth century network of lighthouses. This system represents the first example of cooperation by the Australian colonies in sharing the costs and responsibilities of providing navigational aids.

|

Criterion B – Rarity

This criterion is satisfied by places that have significant heritage value because of [their] possession of uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of Australia’s natural or cultural history.

|

| It is forty eight metres high, which makes it the tallest lighthouse in Australia. It retains the original H Wilkins and Company lantern house and the original timber staircase, a feature that is not common in a stone lighthouse. |

Criterion D – Typicality

This criterion is satisfied by places that have significant heritage values because of [their] importance in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of Australia’s natural or cultural history.

|

| The Cape Wickham Lighthouse is a good example of a lighthouse built during the 1860s. |

Criterion E – Aesthetics

This criterion is satisfied by places that have significant heritage value because of [their] importance in exhibiting particular aesthetic characteristics values by a community or cultural group.

|

| The Cape Wickham Lighthouse makes a dramatic contribution to the rural landscape of the northern tip of King Island. |

5.2 Tasmanian State Heritage Register – Cape Wickham Lighthouse

Cape Wickham Lighthouse is listed on the Tasmanian Heritage Register (THR ID: 3613). The statement of significance and heritage values criteria are directly taken from the listing.

State heritage statement of significance

No statement of significance is provided for places listed prior to 2007.

TAS State heritage criteria

There are eight criterions identified within the Tasmanian Heritage Register – Cape Wickham Lighthouse meets the following five criterions.

State Heritage Register criterion (SHR) | Evidence/Explanation |

SHR Criterion A – The place is important to the course or pattern of Tasmania’s history. | Historically, the Cape Wickham Lighthouse has played an important role in the development of a coastal lighting system and the expansion of commercial activity within the Bass Strait region. The 1861 tower and pre-1918 archaeological remnants of the station settlement are among the oldest structures on King island.

|

SHR Criterion B – The place possesses uncommon or rare aspects of Tasmania’s history.

| The gently tapering form of the Cape Wickham Lighthouse is significant as the tallest light tower in Australia. |

SHR Criterion C – The place has the potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of Tasmania’s history. | The Cape Wickham Lightstation is of historic heritage significance because of its potential to provide information about the early operation of the Lightstation through its archaeological deposits.

|

SHR Criterion D – The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of place in Tasmania’s history. | The Cape Wickham Lighthouse is of historic heritage significance because it represents the principal characteristics of a Mid-Victorian lighthouse.

|

SHR Criterion F – The place has a strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group for social or spiritual reasons. | The Cape Wickham Lighthouse is of a historic heritage significance as a dramatic landmark feature valued by the community.

|

These heritage values, identified and explained in the Commonwealth heritage list and the Tasmanian Heritage Register, will form the basis of the management of Cape Wickham Lighthouse. In the event of necessary works, all criteria will be consulted to inform best practice management of the values associated with the lighthouse. (See Section 7 – Conservation management policies for further information on strategies to conserve Cape Wickham Lighthouse’s heritage values).

5.3 Condition and integrity of the Commonwealth heritage values

Condition is measured on a Good – Fair – Poor scale and incorporates the current condition of the specific value. Integrity is measured on a High – Medium – Low scale which incorporates the value’s intactness.

The Cape Wickham Lighthouse’s heritage values maintain good condition and medium-high integrity (the replacement of the original balcony have had a slight impact on the integrity of Criterion D).

Criteria | Values (including attributes) | Condition | Integrity |

Criteria A – Processes

| The Cape Wickham Lighthouse, built in 1861, is significant as an integral part of Bass Strait's mid-nineteenth century network of lighthouses. This system represents the first example of cooperation by the Australian colonies in sharing the costs and responsibilities of providing navigational aids.

| Good | High |

Criteria B – Rarity

| It is forty eight metres high, which makes it the tallest lighthouse in Australia. It retains the original H Wilkins and Company lantern house and the original timber staircase, a feature that is not common in a stone lighthouse.

| Good | High |

Criteria D – Typicality

| The Cape Wickham Lighthouse is a good example of a lighthouse built during the 1860s.

| Good | Medium – High |

Criteria E – Aesthetic

| The Cape Wickham Lighthouse makes a dramatic contribution to the rural landscape of the northern tip of King Island.

| Good | High |

5.4 Gain/loss of heritage values

Evidence for the potential gain or loss of heritage values will be documented within this section of future versions of this heritage management plan.

6. Opportunities and constraints

6.1 Implications arising from significance

The Commonwealth statement of significance (section 5.1 above) demonstrates that Cape Wickham Lighthouse is a place of considerable heritage value due to its contribution to the 19th century of lighthouses within Bass Strait, its standing as the tallest Australian lighthouse, the retention of its original Wilkins & Co. lantern house and timber staircase, and its aesthetic appeal on the landscape.

The implication arising from this assessment is that key aspects of the place should be conserved to retain this significance. The key features requiring conservation include:

- architectural quality of the building

- original Wilkins Co. lantern house

- original, unique timber staircase

- movable artefacts (see Section 4.2)

- interior spaces and features which are notable for their design, details, and/or their original lighthouse function:

- intermediate floors

- ground floor

- lantern room

- lens assembly

- external spaces and features which are notable for their design, details, and/or their original lighthouse function:

- lantern roof and glazing

- external catwalk, and balcony

- lighthouse walls, windows

Referral and approvals of action

The Act provides that actions:

- taken on Commonwealth land which are likely to have a significant impact on the environment will require the approval of the Minister.

- taken outside Commonwealth land which are likely to have a significant impact on the environment on Commonwealth land, will require the approval by the Minister.

- taken by the Australian Government or its agencies which are likely to have a significant impact on the environment anywhere will require approval by the Minister.

Heritage strategy

If an Australian Government agency owns or controls one or more places with Commonwealth heritage values, it must prepare a heritage strategy within two years from the first time they own or control a heritage place (section 341ZA).

A heritage strategy is a written document that integrates heritage conservation and management within an agency’s overall property planning and management framework. Its purpose is to help an agency manage and report on the steps it has taken to protect and conserve the Commonwealth heritage values of the properties under its ownership or control.

The heritage strategy for AMSA’s AtoN assets was completed and approved by the minister in 2018.[28]

Heritage asset condition report

A heritage asset condition report is a written document that details the heritage fabric of a site with an in-depth description of each architectural and structural element. The document includes: a brief history of the site, the Commonwealth Heritage statement of significance and value criteria, a heritage significance rating for each individual element, and a catalogue of artefacts on-site. The document is also accompanied by up-to-date photos of each structural element. This document operates as a tool for heritage monitoring, and is reviewed and updated biennially.

Aboriginal heritage significance

King Island as a whole is notable for its Aboriginal heritage significance and natural values. Although these values lie outside of the Commonwealth heritage listing curtilage and AMSA’s lease, the potential remains for future works at the lighthouse to impact these values. At the time this plan was written, no plans have been made for future works at Cape Wickham Lighthouse. In the event major works at the lighthouse are to be carried out, AMSA will seek to minimise impacts to the surrounding area by:

- Utilising specific access tracks to ensure no damage to surrounding vegetation,

- Ensuring project footprint is limited to the AMSA lease. In any instance that work is required outside of this footprint, approvals will be sought from the appropriate stakeholders including TAS PWS, and the Office of Aboriginal Affairs (Tas),

- Implementing an appropriate discovery plan in the instance Aboriginal cultural heritage is suspected and/or found.

6.2 Framework: sensitivity to change

The heritage values identified by both Commonwealth and state demonstrate Cape Wickham Lighthouse is of high significance. Therefore, work actioned by AMSA on the lighthouse’s fabric harnesses the potential to reduce or eradicate the significance of the site’s heritage values.

Conservation works, including restoration and reconstruction, or adaptation works of the absolute minimum so as to continue the lighthouse’s usefulness as an AtoN are the only works that should be actioned by AMSA on Cape Wickham Lighthouse. Some exceptions are made for health and safety requirements, however any and all work carried out must be conducted in line with heritage considerations and requirements of the EPBC Act.

The table below demonstrates the level of sensitivity attributed to the various elements of the fabric register in the face of change. These are measured on a High-Moderate-Low spectrum depending on the action’s possible threat to the site’s heritage values.

High sensitivity

High sensitivity to change includes instances wherein a change would pose a major threat to the heritage value of a specific fabric, or the lighthouse as a whole. A major threat is one that would lead to substantial or total loss of the heritage value.

Moderate sensitivity

Moderate sensitivity to change includes instances wherein a change would pose a moderate threat to the heritage value of a specific fabric, or would pose a threat to the heritage significance of a specific fabric in another part of the building. A moderate threat is one that would diminish the heritage value, or diminish the ability of an observer to appreciate the value.

Low sensitivity

Low sensitivity to change includes instances wherein a change would pose little to no threat to the heritage value of a specific fabric, and would pose little to no threat to heritage significance in another part of the building.

Component | Level of sensitivity | Nature of change impacting heritage values

|

Cape Wickham Lighthouse structure | High |

|

Low |

| |

Ground, and intermediate floors | High |

|

Low |

| |

Timber staircase | High |

|

Low |

| |

Balcony | High |

|

Low |

| |

Lens assembly, and pedestal | Moderate |

|

Low |

| |

Lantern house | High |

|

Low |

|

6.3 Statutory and legislative requirements

The following table outlines the statutory and legislative requirements relevant to the conservation and management of Cape Wickham Lighthouse.

Act or Code | Description |

Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) | The Environment Protection & Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) requires agencies to prepare management plans that satisfy the obligations included in Schedule 7A and 7B of the EPBC Regulations. |

Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Regulations 2000 (Cth) | The Commonwealth Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment has determined these principles to guide for excellence in managing heritage properties.

- Have a particular interest in, or associations with, the place; and - May be affected by the management of the place

|

AMSA Heritage Strategy | As the custodian of many iconic sites, the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) has long recognised the importance of preserving their cultural heritage. This Heritage Strategy is in response to section 341ZA of the EPBC Act which obliges AMSA to prepare and maintain a heritage strategy, along with obliging AMSA to:

The strategy derives from the AMSA Corporate Plan and achievements are reported through the AMSA Annual Report.[29]

|

Navigation Act 2012 (Cth) | Part 5 of the Act outlines AMSA’s power to establish, maintain and inspect marine aids to navigation (such as Cape Wickham Lighthouse). (1) AMSA may: (a) Establish and maintain aids to navigation; and (b) Add to, alter or remove any aid to navigation that is owned or controlled by AMSA; and

(c) Vary the character of any aid to navigation that is owned or controlled by AMSA.

(2) AMSA, or person authorised in writing by AMSA may, at any reasonable time of the day or night: (a) Inspect any aid to navigation or any lamp or light which, in the opinion of AMSA or the authorised person, may affect the safety or convenience of navigation, whether the aid to navigation of the lamp or light is the property of: (i) A state or territory; or (ii) An agency of a state or territory; or (iii) Any other person; and

(b) Enter any property, whether public or private, for the purposes of an inspection under paragraph (a); and

(c) Transport, or cause to be transported, any good through any property, whether public or private, for any purpose in connection with: (i) The maintenance of an aid to navigation that is owned or controlled by AMSA; or (ii) The establishment of any aid to navigation by AMSA.

|

Australian Heritage Council Act 2003 (Cth) | This Act establishes the Australian Heritage Council, whose functions are:

|

TAS Historic Cultural Heritage Act 1995 (Tas) | This Act establishes the Tasmanian Heritage Council.

7 General functions and powers of Heritage Council (1) The functions of the Heritage council are – (a) to advise the Minister on matters relating to Tasmania's historic cultural heritage and the measures necessary to conserve that heritage for the benefit of the present community and future generations; and

(b) to work within the planning system to achieve the proper protection of Tasmania's historic cultural heritage; and

(c) to co-operate and collaborate with Federal, state and local authorities in the conservation of places of historic cultural heritage significance; and

(d) to encourage and assist in the proper management of places of historic cultural heritage significance; and

(e) to encourage public interest in, and understanding of, issues relevant to the conservation of Tasmania's historic cultural heritage; and

(f) to encourage and provide public education in respect of Tasmania's historic cultural heritage; and

(g) to assist in the promotion of tourism in respect of places of historic cultural heritage significance; and

(h) to keep proper records, and encourage others to keep proper records, of places of historic cultural heritage significance; and

(i) to perform any other function the minister determines.

(2) The Heritage Council may do anything necessary or convenient to perform its functions.

|

National Parks and State Reserve Management 2002 (Tas) | Schedule 1, Section 8: Historic site

The following objectives: (a) to conserve sites or areas of historic cultural significance; (b) to conserve natural biological diversity; (c) to conserve geological diversity; (d) to preserve the quality of water and protect catchments; (e) to encourage education based on the purposes of reservation and the natural or cultural values of the historic site, or both; (f) to encourage research, particularly that which furthers the purposes of reservation; (g) to protect the historic site against, and rehabilitate the historic site following, adverse impacts such as those of fire, introduced species, diseases and soil erosion on the historic site’s natural and cultural values and on assets within and adjacent to the historic site; (h) to encourage tourism, recreational use and enjoyment consistent with the conservation of the historic site’s natural and cultural values; (i) to encourage cooperative management programs with Aboriginal people in areas of significance to them in a manner consistent with the purposes of reservation and the other management objectives.

|

Building Code of Australia/National Construction Code | The Code is the definitive regulatory resource for building construction, providing a nationally accepted and uniform approach to technical requirements for the building industry. It specifies matters relating to building work in order to achieve a range of health and safety objectives, including fire safety.

As far as possible, Commonwealth agencies aim to achieve compliance with the Code, although this may not be entirely possible because of the nature of and constraints provided by existing circumstances, such as an existing building.

|

Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (Cth) | The objectives of this Act include: (1) The main object of this Act is to provide for a balanced and nationally consistent framework to secure the health and safety of workers and workplaces by:

a) protecting workers and other persons against harm to their health, safety and welfare through the elimination of minimisation of risks arising from work; and

b) providing for fair and effective workplace representation, consultation, co-operation and issue resolution in relation to work health and safety; and

c) encouraging unions and employer organisations to take a constructive role in promoting improvements in work health and safety practices, and assisting persons conduction businesses or undertakings and workers to achieve a healthier and safer working environment; and

d) promoting the provision of advice, information, education and training in relation to work health and safety; and

e) securing compliance with this Act through effective and appropriate compliance and enforcement measures; and

f) ensuring appropriate scrutiny and review of actions taken by persons exercising powers and performing functions under this Act; and

g) providing a framework for continuous improvement and progressively higher standards pf work health and safety; and

h) maintaining and strengthening the national harmonisation of laws relating to work health and safety and to facilitate a consistent national approach to work health and safety in this jurisdiction. [Quoted from Division 2 of Act]

This has implications for Cape Wickham Lighthouse of Australia as it is related to AMSA staff, contractors and visitors.

|

6.4 Operational requirements

As a working AtoN, the operational needs of Cape Wickham Lighthouse are primarily concerned with navigational requirements

Below are the operational details and requirements of Cape Wickham light as outlined by AMSA.

Navigational requirement for AMSA’s AtoN Site | ||

1 | Objective/rationale | An AtoN is required at Cape Wickham on the northern tip of King Island in the middle of the western entrance to the Bass Strait. It provides both a landfall mark to the Strait and a navigation mark for vessels transiting either east / west through it or across it. The Strait has complex sea limits and the AtoN assists with positioning within these limits. The AtoN also assists in keeping vessels clear of the shoals that lie 2 nautical miles north-east and 5 nautical miles north-west of it.

|

2 | Required type(s) of AtoN | A fixed structure is required to act as a day mark. A distinctive light is required for use at night.

|