The Australian Maritime Safety Authority makes this heritage management plan under section 341S of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) for Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse.

23 June 2022

Mick Kinley

Chief Executive Officer

Copyright

© Australian Maritime Safety Authority

The Australian Maritime Safety Authority encourages the dissemination and exchange of information provided in this publication.

Except as otherwise specified, all material presented in this publication is provided under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. This excludes:

- the Commonwealth Coat of Arms

- this department's logo

- content supplied by third parties.

The Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The details of the version 4.0 of the licence are available on the Creative Commons website, as is the full legal code for that licence.

Third Party Copyright

Some material in this document, made available under the Creative Commons Licence framework, may be derived from material supplied by third parties. The Australian Maritime Safety Authority has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© [name of third party]’ or ‘Source: [name of third party]’. Permission may need to be obtained from third parties to re-use their material.

Acknowledgements

The Australian Maritime Safety Authority acknowledges that the lighthouse is located within traditional Country.

Contact

Comments or questions regarding this document should be addressed to:

The Australian Maritime Safety Authority,

Manager Asset Management and Preparedness,

PO Box 10790,

Adelaide Street, Brisbane QLD 4000

Phone: (02) 6279 5000 (switchboard)

Email: Heritage@amsa.gov.au

Website: www.amsa.gov.au

Attribution

AMSA’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording:

Source: Australian Maritime Safety Authority Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse Heritage Management Plan – 2022

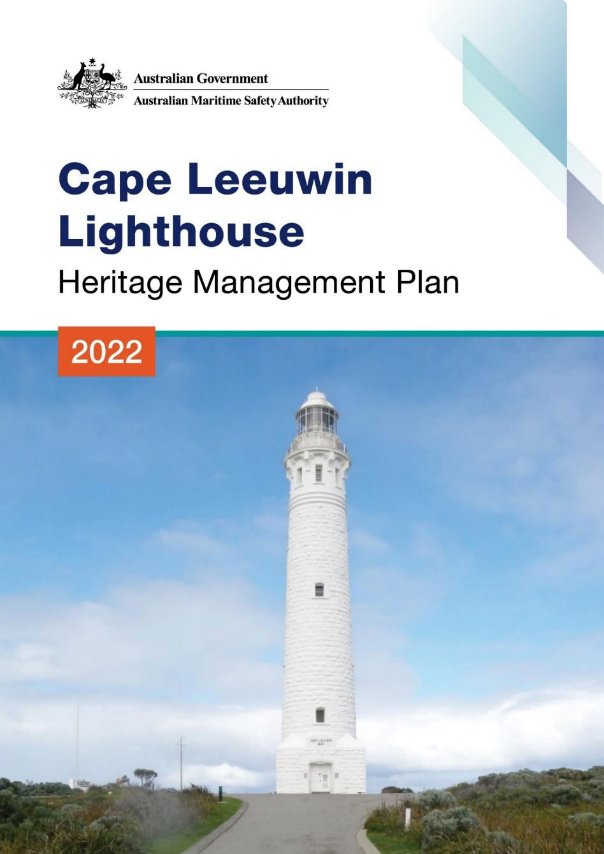

Front cover image

Figure 1. Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse (© AMSA, 2017)

More information

For enquiries regarding copyright including requests to use material in a way that is beyond the scope of the terms of use that apply to it, please contact us through our website: www.amsa.gov.au

Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse

Heritage Management Plan

2022

Table of Contents

Executive summary

1. Introduction

1.1 Background and purpose

1.2 Heritage management plan objectives

1.3 Methodology

1.4 Status

1.5 Authorship

1.6 Acknowledgements

1.7 Language

1.8 Previous reports

1.9 Sources of information and images

2. Cape Leeuwin Lightstation site

2.1 Location

2.2 Setting and landscape

2.3 Lease and ownership

2.4 Listings

2.5 Access

3. History

3.1 General History of lighthouses in Australia

3.2 The Commonwealth Lighthouse Service

3.3 Western Australian lighthouse administration

3.4 Cape Leeuwin: a history

3.5 Planning a lighthouse

3.6 Lighthouse keepers

3.7 Chronology of major events

3.8 Changes and conservation over time

3.9 Summary of current and former uses

3.10 Summary of past and present community associations

3.11 Unresolved questions or historical conflicts

3.12 Recommendations for further research

4. Fabric

4.1 Fabric register

4.2 Related objects and associated AMSA artefacts

4.3 Comparative analysis

5. Heritage significance

5.1 Commonwealth heritage listing – Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse

5.2 WA State heritage register – Cape Leeuwin Lightstation

5.3 Condition and integrity of the Commonwealth heritage values

5.4 Gain/loss of heritage values

6. Opportunities and constraints

6.1 Implications arising from significance

6.2 Framework: sensitivity to change

6.3 Statutory and legislative requirements

6.4 Operational requirements and occupier needs

6.5 Proposals for change

6.6 Potential pressures

6.7 Process for decision-making

7. Conservation management principles and policies

8. Policy implementation plan

8.1 Plan and schedule

8.2 Monitoring and reporting

Appendices

Appendix 1. Glossary of heritage conservation terms

Appendix 2. Glossary of historic lighthouse terms relevant to Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse

Appendix 3. Cape Leeuwin light details

Appendix 4. Table demonstrating compliance with the EPBC Regulations

Reference List

End notes

List of Figures

Figure 1. Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse (© AMSA, 2017)

Figure 2. Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse, Western Australia (© AMSA, 2017)

Figure 3. Planning process applied for heritage management (Source: Australia ICOMOS, 1999)

Figure 4. Location of Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse (Map data: © 2021 Google, TerraMetrics)

Figure 5. View of lightstation from Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse tower (© AMSA, 2017)

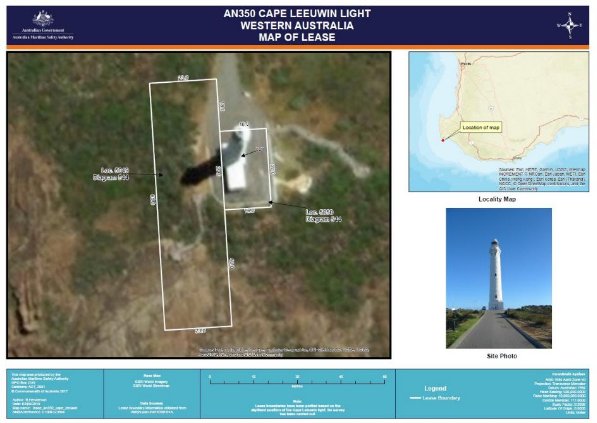

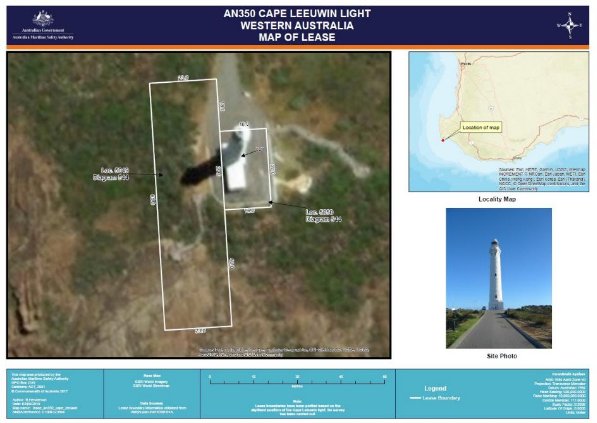

Figure 6. AMSA Cape Leeuwin Map of Lease, 2018 (Source: Esri, DigitalGlobe, GeoEye, Earthstar Geographics, CNES/Airbus DS, USDA, USGA, AeroGRID, IGN, and the GIS User Community)

Figure 7. View of access road, Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse (© AMSA, 2018)

Figure 8. Incandescent oil vapour lamp by Chance Brothers (Source: AMSA)

Figure 9. Dioptric lens on display at Narooma (Source: AMSA)

Figure 10. Dalén’s system – sunvalve, mixer, and flasher (Source: AMSA)

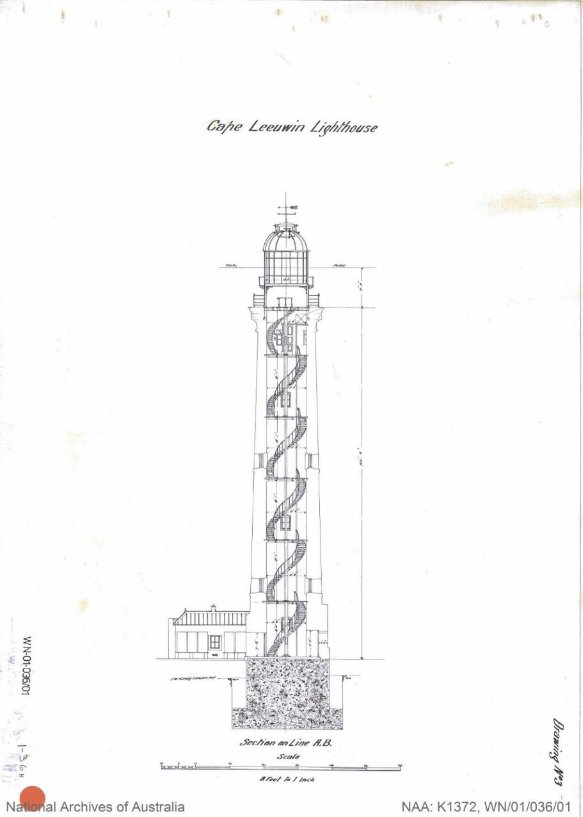

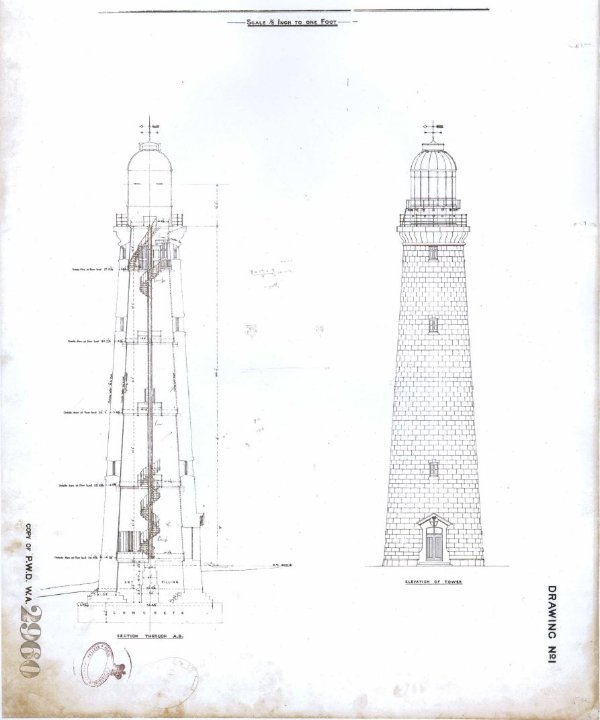

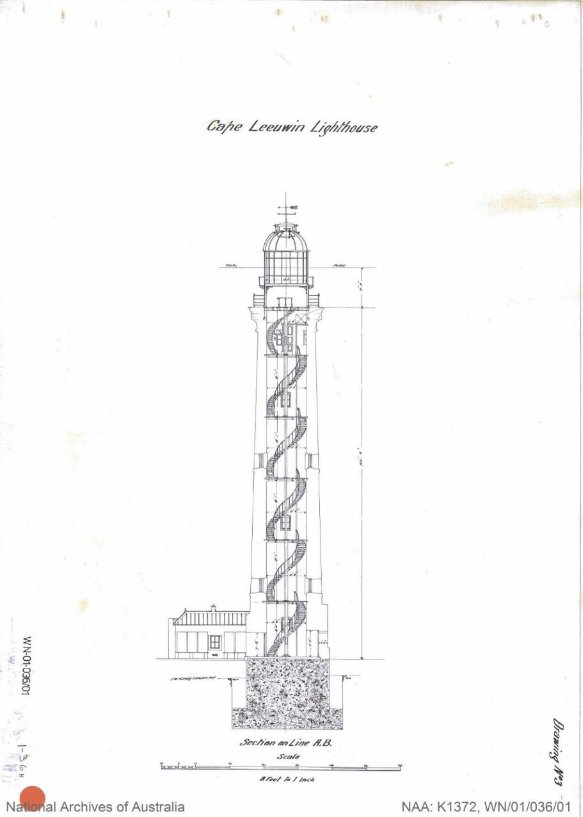

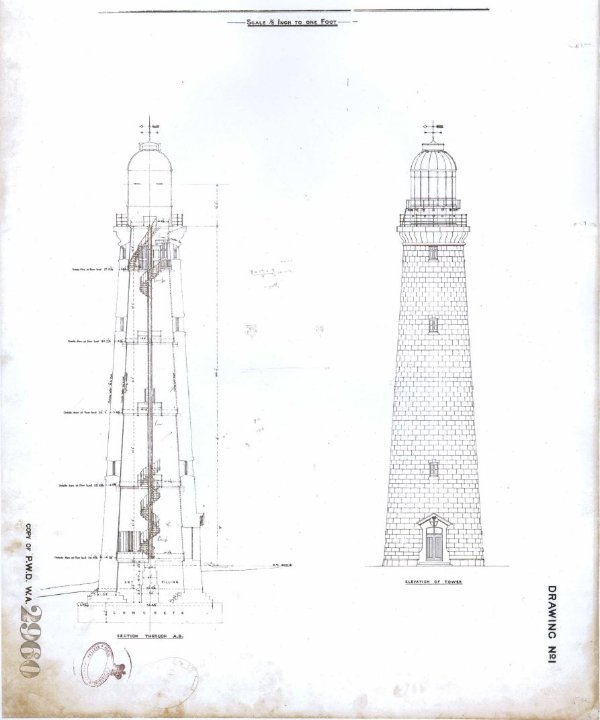

Figure 11. Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse drawing. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia, NAA: K1371, WN0103601 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

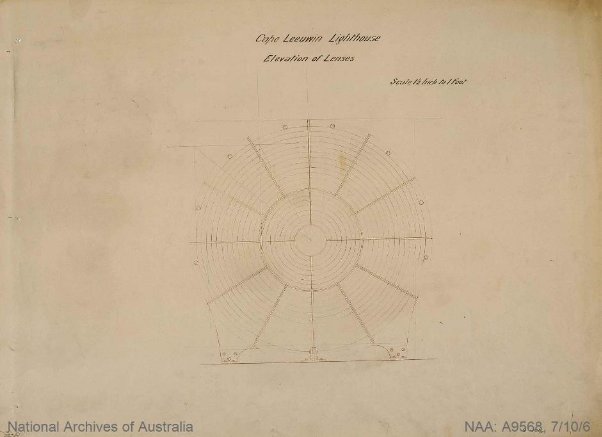

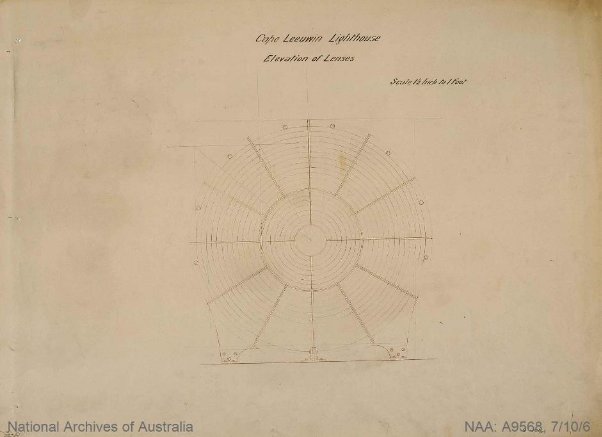

Figure 12. Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse 1st Order Chance Brothers Lens. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia, NAA: A9568, 7/10/6 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Figure 13. View of Wadjemup (Rottnest Island) Lighthouse (© AMSA, 2017)

Figure 14. View of Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse (© AMSA, 2010)

Figure 15. Wadjemup (Rottnest Island) Lighthouse drawing 1884-85. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia, NAA: K1372, WN0101401 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

Figure 16. Repainting Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse (© AMSA, 2002)

Executive Summary

Placed on the Commonwealth Heritage List in 2004, Cape Leeuwin Lightstation contributed to the establishment of marine Aids to Navigation (AtoN) along the Western Australian coastline. The lighthouse is known for its original lens array and mercury bath system, aesthetics, and its inherent characteristics of a late nineteenth century lighthouse complex.

Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse was listed on the Western Australia state heritage database in 2005 for its aesthetic, historic, scientific and social value, in addition to its significant rarity and representation.

Built in 1896, the lightstation is situated approximately nine kilometres south of Augusta along the Australian south-west coast. The lightstation comprises of a lighthouse tower, three keepers’ cottages, an education centre/office, staffroom and store shed. The larger part of the lightstation is managed by the Western Australian Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA). The lightstation is open to visitors all year.

Although the lighthouse remains fitted with its original lens array and mercury float pedestal, it now operates on an automated mechanism as part of AMSA’s network of AtoNs. The equipment is serviced by AMSA’s maintenance contractor who visits at least twice each year. AMSA officers visit on an ad hoc basis for auditing, project and community liaison purposes.

This heritage management plan concerns the lighthouse, however it also addresses the management of the surrounding precinct and land. The plan is intended to guide AMSA’s decisions and actions. AMSA has prepared this plan to integrate the heritage values of the lightstation in accordance with the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act), and the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Regulations 2000 (Cth) (EPBC Regulations).

Well-built and generally well-maintained, the lighthouse precinct is in relatively good, stable condition. The policies and management guidelines set out in this heritage management plan strive to ensure the Commonwealth heritage values of Cape Leeuwin Lightstation are recognised, maintained and preserved for future generations.

Figure 2. Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse, Western Australia (© AMSA, 2017)

Figure 2. Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse, Western Australia (© AMSA, 2017)

1. Introduction

1.1 Background and purpose

The Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) is the Commonwealth agency responsible for coastal AtoN. AMSA’s network includes the Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse, built by the Western Australian State Government in 1896.

Section 341S of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act) requires AMSA to prepare a management plan for Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse that addresses the matters prescribed in Schedules 7A and 7B of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Regulations 2000 (Cth) (EPBC Regulations). The principal features of this management plan are:

- a description of the place, its heritage values, their condition and the method used to assess its significance

• an administrative management framework

• a description of any proposals for change

• an array of conservation policies that protect and manage the place

• an implementation plan

• ways the policies will be monitored and how the management plan will be reviewed.

AMSA has prepared this heritage management plan to guide the future conservation of the place. This plan provides the framework and basis for the conservation and best practice management of the Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse in recognition of its heritage values. The policies in this plan indicate the objectives for identification, protection, conservation and presentation of the commonwealth heritage values of the place. Figure 3 shows the basic planning process applied.

Figure 3. Planning process applied for heritage management (Source: Australia ICOMOS, 1999)

1.2 Heritage management plan objectives

The objectives of this heritage management plan are to:

- protect, conserve and manage the Commonwealth heritage values of the Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse;

- interpret and promote the Commonwealth heritage values of the Cape Leeuwin Lightstation;

- manage use of the lighthouse; and use best practice standards, including ongoing technical and community input, and apply best available knowledge and expertise when considering actions likely to have a substantial impact on Commonwealth heritage values.

In undertaking these objectives, this plan aims to:

- Provide for the protection and conservation of the heritage values of the place while minimising any impacts on the environment by applying the relevant environmental management requirements in a manner consistent with Commonwealth heritage management principles.

- Take into account the significance of the surrounding region as a cultural landscape occupied by Aboriginal people over many thousands of years.

- Recognise that the site has been occupied by lease holders since the early 20th century.

- Encourage site use that is compatible with the historical fabric, infrastructure and general environment.

- Record and document maintenance works, and changes to the fabric, in the Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse fabric register (see Section 4).

The organisational planning cycle and associated budgeting process is used to confirm requirements, allocate funding, and manage delivery of maintenance activities. Detailed planning for the aids to navigation network is managed through AMSA’s internal planning processes.

An interactive map showing many of AMSA’s heritage sites, including Cape Leeuwin, can be found on AMSA’s Interactive Lighthouse Map[i].

1.3 Methodology

The methodology used in the preparation of this plan is consistent with the recommendations of The Burra Charter and with the requirements of Chapter 5, Part 15 Division 1A of the EPBC Act. In particular, the plan:

- details the history of the site based on information sourced from archival research, expert knowledge and documentary resources.

- provides a description of the site based on information sourced from site inspection reports and fabric registers.

- details the Commonwealth heritage criterions satisfied by Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse as set out by the EPBC Regulations.

The criterion set out at Schedule 7A (h) (i-xiii) informed the development of the required policies for the management of the Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse, in conjunction with input from the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment on best practice management.

Consultation

In the preparation of the plan, AMSA consulted with the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Shire of Augusta Margaret River (AMR Shire), and the Margaret River Busselton Tourism Inc. These groups provided valuable information on the management of the larger lightstation, fauna and flora in the vicinity of the lighthouse, and processes relating to site-use.

AMSA initiated contact with the Undalup Association Inc. and the South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council (SWALSC) under the direction of Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage (Aboriginal Heritage, WA) and AMR Shire in preparation of the plan. As of yet, no response has been received. Future versions of the plan will include an update on this consultation progress.

The plan was advertised within The Australian newspaper, and on AMSA’s external website in June 2020, and the general public were invited to provide feedback in accordance with the EPBC Regulations. Comments received were incorporated within the plan.

AMSA submitted the draft plan to the Heritage Branch of the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment who provided feedback on the draft. These comments were incorporated into the final document.

The draft plan was submitted to the Australian Heritage Council and was endorsed by the Minister for the Environment on 23 March 2022.

1.4 Status

This plan has been adopted by AMSA in accordance with Schedule 7A (Management plans for Commonwealth Heritage places) and Schedule 7B (Commonwealth Heritage management principles) of the EPBC Regulations to guide the management of the place and for inclusion in the Federal Register of Legislative Instruments.

1.5 Authorship

This plan has been prepared by AMSA. At the initial time of publication, the Australian Maritime Systems Group (AMSG) is the contracted maintenance provider for the Commonwealth Government’s AtoN network including the Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse.

1.6 Acknowledgements

AMSA acknowledges the professional assistance of the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (WA), Shire of Augusta Margaret River (AMR Shire), the Margaret River Busselton Tourism Inc., and Aboriginal Heritage (WA).

1.7 Language

For clarity and consistency, some words in this plan, such as restoration, reconstruction, and preservation, are used with the meanings defined in the Burra Charter[ii]. (See Appendix 1. Glossary of Heritage Conservation Terms).

Also see Appendix 2. Glossary of lighthouse terminology relevant to Cape Leeuwin which sets out the technical terminology used in this plan.

1.8 Previous reports

A Conservation Plan was produced by Danvers Architects for AMSA in 1992.

A Heritage Lighthouse Report was produced by Peter Marquis-Kyle (and reviewed by AMSG) for AMSA in 2007.

A Heritage Asset Condition Report 4th Revision was produced by AMSG in 2020 for AMSA.

1.9 Sources of information and images

This plan has used a number of sources of information. This includes the National Archives of Australia (NAA), the National Library of Australia (NLA) and AMSA’s heritage collection.

2. Cape Leeuwin Lightstation Site

2.1 Location

Cape Leeuwin Lightstation is located on Cape Leeuwin (Doogalup) in Western Australia – approximately six miles (9.65 km) south of the township of Augusta, and approximately 11 miles (17.7 kilometres) south of Hamelin Bay.

Coordinates: 34º 22.4900’ S, 115º 08.1800’ E

Figure 4. Location of Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse (Map data: © 2021 Google, TerraMetrics)

2.2 Setting and landscape

Situated within the Leeuwin-Naturaliste National Park, the lightstation is located on Cape Leeuwin (Doogalup), a bare, low-lying bluff considered the most south-westerly point of Australia. Owing to the forcefulness of the south westerlies, vegetation is limited on the cape (low shrubs and ground covers). A collection of islands and rocks extend from the cape and the nearest settlement is Augusta (est. 1830).

Figure 5. View of lightstation from Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse tower (© AMSA, 2017)

Fauna and flora

Situated within Leeuwin-Naturaliste National Park, the larger Cape Leeuwin (Doogalup) region is abundant in native flora and fauna. Taken from the Leeuwin-Naturaliste management plan (2015)[iii], the following species data has been sourced from faunal surveys taken within the national park:

- 29 mammal species (including 4 species of bat)

- 128 bird species

- 11 frog species

- 33 reptile species

- 9 fish species

- 54 invertebrate species

The following faunal species have been listed as threatened:

- quokka (Setonix brachyurus)

- western quoll (Dasyurus geoffroii)

- brush-tailed phascogale (Phascogale tapoatafa)

- western ringtail possum (Pseudocheirus occidentalis)

- forest red-tailed black cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus banksia naso)

- Baudin’s cocktatoo (C. baudinii)

- Carnaby’s cockatoo (C. latirostris)

- Hutton’s shearwater (Puffinus huttoni)

- Australasian bittern (Botaurus poiciloptilus)

- white-bellied frog (Geocrinia alba)

- Balston’s pygmy perch (Nannatherina balstoni)

- western mud minnow (Galaxiella munda)

- Cape Leeuwin freshwater snail (Austroassiminea letha)

- Margaret River marron or hairy marron (Cherax tenuimanus)

- Dunsborough borrowing crayfish (Engaewa reducta)

The Leeuwin-Naturaliste National Park contains 1,577 native flora species of 198 families. The following floral species have been listed as rare under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (WA):

- Banksia nivea

- Scott River boronia (Boronia exilis)

- Caladenia excels

- Caladenia lodgeana

- Dunsborough spider orchid (Caladenia viridescens)

- Ironstone darwinia (Darwinia ferricola)

- Eucalyptus phylacis

- Grevillea brachstylis

- Augusta kennedia (Kennedia lateritia)

- Lambertia orbifolia

- Naturaliste nancy (Wurmbea calcicola)

- Diel’s currant bush (Leptomeria dielsiana)

The Leeuwin-Naturaliste Capes Area Parks and Reserves Management Plan 81 was released in 2015 and contains further information on the biodiversity of the region.[iv]

Figure 6. AMSA Cape Leeuwin Map of Lease, 2018 (Source: Esri, DigitalGlobe, GeoEye, Earthstar Geographics, CNES/Airbus DS, USDA, USGA, AeroGRID, IGN, and the GIS User Community)

Figure 6. AMSA Cape Leeuwin Map of Lease, 2018 (Source: Esri, DigitalGlobe, GeoEye, Earthstar Geographics, CNES/Airbus DS, USDA, USGA, AeroGRID, IGN, and the GIS User Community)

2.3 Lease and ownership

AMSA holds a lease for the lighthouse from the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (WA) (formerly the Department of Conservation and Land Management). The current lease was signed on 1 December 2000.

The AMSA lease consists of two parcels of land equalling a total surface area of 2,387m2:

• Lot 1: 432m2

• Lot 2: 1,955m2

(See Figure 6 for map of lease area).

Due to interest in the site from the general public, a tourism licence between AMSA and DBCA was signed on 1 December 2000. The licence permits the practice of tours inside the lighthouse tower.

2.4 Listings

The table below details the various heritage listings of the Cape Leeuwin Lightstation.

Register | ID |

Commonwealth Heritage List | 1054164[v] |

Register of the National Estate | 9399 |

Western Australia Heritage Register | 001045[vi] |

2.5 Access

The Cape Leeuwin Lightstation can be accessed via Leeuwin Rd, a sealed vehicle track which terminates as a vehicle parking site. Further vehicle access is only permitted for authorised personnel. In order to reach the lighthouse tower, all visitors are required to travel via walking track to the base of the tower. Owing to the existence of concrete apron paving, walking access is available around the lighthouse base.

Figure 7. View of access road, Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse (© AMSA, 2018)

Figure 7. View of access road, Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse (© AMSA, 2018)

3. History

3.1 General history of lighthouses in Australia

The first lighthouse to be constructed along Australian soil was Macquarie Lighthouse, located at the entrance to Port Jackson, NSW. First lit in 1818, the cost of the lighthouse was recovered through the introduction of a levy on shipping. This was instigated by Governor Lachlan Macquarie, who ordered and named the light.

The following century oversaw the construction of hundreds of lighthouses around the country. Constructing and maintaining a lighthouse were costly ventures that often required the financial support of multiple colonies. However, they were deemed necessary aids in assisting the safety of mariners at sea. Lighthouses were firstly managed by the colony they lay within, with each colony developing their own style of lighthouse and operational system. Following Federation in 1901, which saw the various colonies unite under one Commonwealth government, lighthouse management was transferred from state hands to the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service.

Lamps and optics – an overview

Lighthouse technology has altered drastically over the centuries. Eighteenth century lighthouses were lit using parabolic mirrors and oil lamps. Documentation of early examples of parabolic mirrors in the United Kingdom, circa 1760, were documented as consisting of wood and lined with pieces of looking glass or plates of tin. As described by Searle, ’When light hits a shiny surface, it is reflected at an angle equal to that at which it hit. With a light source is placed in the focal point of a parabolic reflector, the light rays are reflected parallel to one another, producing a concentrated beam’.[vii]

Figure 8. Incandescent oil vapour lamp by Chance Brothers (Source: AMSA)

Figure 9. Dioptric lens on display at Narooma (Source: AMSA)

In 1822, Augustin Fresnel invented the dioptric glass lens. By crafting concentric annular rings with a convex lens, Fresnel had discovered a method of reducing the amount of light absorbed by a lens. The Dioptric System was adopted quickly with Cordouran Lighthouse (France), which was fitted with the first dioptric lens in 1823. The majority of heritage-listed lighthouses in Australia house dioptric lenses made by others such as Chance Brothers (United Kingdom), Henry-LePaute (France), Barbier, Bernard & Turenne (BBT, France) and Svenska Aktiebolaget Gasaccumulator (AGA of Sweden). These lenses were made in a range of standard sizes, called orders—see ‘Appendix 2. Glossary of lighthouse Terms relevant to Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse’.

Early Australian lighthouses were originally fuelled by whale oil and burned in Argand lamps, and multiple wicks were required in order to create a large flame that could be observed from sea. By the 1850s, whale oil had been replaced by colza oil, which was in turn replaced by kerosene, a mineral oil.

In 1900, incandescent burners were introduced. This saw the burning of fuel inside an incandescent mantle, which produced a brighter light with less fuel within a smaller volume. Light keepers were required to maintain pressure to the burner by manually pumping a handle as can be seen in Figure 8.

In 1912, Swedish engineer Gustaf Dalén, was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for a series of inventions relating to acetylene-powered navigation lights. Dalén’s system included the sun valve, the mixer, the flasher, and the cylinder containing compressed acetylene. Due to their efficiency and reliability, Dalén’s inventions led to the gradual de-staffing of lighthouses. Acetylene was quickly adopted by the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service from 1915 onwards.

Large dioptric lenses, such as that shown in Figure 9, gradually decreased in popularity due to cost and the move towards unmanned automatic lighthouses. By the early 1900s, Australia had stopped ordering these lenses with the last installed at Eclipse Island in Western Australia in 1927. Smaller Fresnel lenses continued to be produced and installed until the 1970s when plastic lanterns, still utilising Fresnel’s technology, were favoured instead. Acetylene remained in use until it was finally phased out in the 1990s.

In the current day, Australian lighthouses are lit and extinguished automatically using mains power, diesel generators, and solar-voltaic systems.

3.2 The Commonwealth Lighthouse Service

When the Australian colonies federated in 1901, it was decided that the new Commonwealth Government would be responsible for coastal lighthouses. This included only the major lights used by vessels travelling from port to port, not the minor lights used for navigation within harbours and rivers. There was a delay before this new arrangement came into effect and the existing lights continued to be operated by the states.

Since 1915, various Commonwealth departments have managed lighthouses. AMSA, established under the Australian Maritime Safety Authority Act 1990 (Cth), is now responsible for operating Commonwealth lighthouses and other marine aids to navigation, along with its other functions.

Figure 10. Dalén’s system – sunvalve, mixer and flasher (Source: AMSA)

3.3 Western Australian lighthouse administration

The table below details the authorities of WA lighthouse management from 1915 to present.

Time Period | Administration |

1915 – 1921 | Lighthouse Branch, No 1. District (Western Australia and Northern Territory), Fremantle. |

1921 – 1927 | District Lighthouse Officer and Deputy Director of Navigation, Western Australia. |

1927 – 1963 | Deputy Director of Lighthouses and Navigation, Western Australia. |

1963 – 1972 | Department of Shipping and Transport, Regional Controller, Western Australia. |

1972 – 1977 | Department of Transport [III], Western Australia. |

1977 – 1982 | Department of Transport [III], Western Australia Region. |

1982 – 1983 | Department of Transport and Construction, Regional Office, Western Australia. |

1983 – 1987 | Department of Transport [IV], Western Australian Region. |

1987 – 1990 | Department of Transport and Communications, Regional Office Western Australia. |

1991 – | Australian Maritime Safety Authority |

3.4 Cape Leeuwin: a history

Aboriginal history

The Wardandi, one of the fourteen Noongar tribes, have significant links to the cape which is known as Doogalup. The cape has heritage significance.

Further consultation is required and this section will be updated in future versions of the plan.

Early European history

Cape Leeuwin was named by Matthew Flinders, English navigator and cartographer, on 7 December 1801 for its proximity to the region named Leeuwin’s Land by Dutch navigators in 1622[viii].

The state of Western Australia was proclaimed on 18 June 1829, shortly followed by groups of settlers to the southwest coast. In the following decades, land was divided and large pastoral leases taken up as the timber industry flourished. In 1830, London surveyor, James Woodward Turner, arrived on the Emily Taylor with the first group of settlers to the area. He was granted 3,000 acres of land. Among these parcels of land was a section of Cape Leeuwin (Doogalup) which would later become the site of the lighthouse.

During the 1880s, Turner sold the Cape Leeuwin property to MC Davis before it was passed to Millars’ Karri & Jarrah Company in 1902. The Commonwealth eventually acquired the lighthouse site in 1915[ix].

3.5 Planning a lighthouse

Why Cape Leeuwin?

In the 1850s, the state of Western Australia set out to establish a lighthouse in its south-western corner. A number of potential dangers had been identified surrounding the Cape and were addressed in initial discussions on the construction of a light.

It was submitted that, in the interests of navigation and the increasing carrying trade of the Australian Colonies, a Lighthouse is urgently required at Cape Leeuwin…[x]

The P & O Mail Steamers bound from Point-de-Galle to Australian Ports generally shape their course from 20 to 25 miles S.W. of Cape Leeuwin, and then haul up to make the land off the White Topped Rocks or Chatham Island to avoid this dangerous corner, especially after Westerly gales, and Leeuwin, as well as the question of the existence of the Rambler Rock[xi].

A number of shipwrecks had been recorded in the vicinity of Cape Leeuwin:

• 1849: The schooner Bee wrecked off Cape Leeuwin[xii]

• 1857: The Enterprise wrecked at Flinders Bay[xiii]

• 1872: The Hokitika wrecked at Geographe Rock (20 km off the Cape)[xiv]

• 1878: The brigantine Salve wrecked in Flinders Bay[xv]

Cape Leeuwin’s position on the far south-western corner of the Australian continent proved critical as a cornerstone along the great southern coast-line shipping route – one of the busiest sea traffic routes on the Australian coast.

The necessity of a light at Cape Leeuwin is unanimously agreed upon by the Commanders of this Company who have had experience of the Australian coast, and it is also their general opinion that such light should be a bright flash one of the first order, visible at a distance of not less than 20 miles in clear weather[xvi].

Additionally, the abundance of limestone resources in the area further cemented the choice of Cape Leeuwin as this could be used as the primary construction material, reducing costs.

Despite avid discussions, little action was taken until the 1873 Conference of the Principal Marine Officers of Marine Departments of the Australasian Colonies restarted efforts to construct a station on the south-western corner. Delays continued well into the 1890’s until the premier of Western Australia, Sir John Forrest, made the executive decision to fund the construction of a lighthouse from his own treasury. Initially advocating for a lighthouse to be constructed on an island off the coast, Sir Forrest was persuaded from this decision after discussions proved such a venture would be too costly. The abundance of limestone resources found on Cape Leeuwin (Doogalup) could be used as the primary construction material – an advantage that secured the site[xvii].

With the site and necessary monetary support secured, planning for a lighthouse at Cape Leeuwin began in 1894.

Design

William T Douglass, of the renowned British lighthouse engineers, served as consultant engineer and architect for the Cape Leeuwin light. His designs incorporated local stone resources, limestone and granite.

However, the colonial architect of the time, George T Poole, made modifications to Douglass’ designs. Fenestration, the base shape of the tower, and the number of windows was altered resulting in completion of a lighthouse in 1896 that didn’t match Douglass’ original design[xviii].

Figure 11. Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse drawing. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia, NAA: K1371, WN/01/036/01 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

The plans for the lighthouse indicated the desire for a limestone tower and quarters with a supplementary red light. Alongside the tower, two cottages were to be constructed of limestone which would serve as the residence of the keepers.

Construction

On 17 January 1895, tenders were called by the Director of Public Works, Mr AW Venn for construction of a lighthouse. Davies and Wishart had their tender of £7,782.11.6 accepted and were chosen as the successful contractors for the lighthouse’s construction (price excluded dome and apparatus). The lantern allegedly cost an additional £425 and the optical apparatus a further £4,069[xix].

In August 1895, the iron barque West Riding sailing from London was declared ‘lost’ after it failed to arrive in Fremantle. The barque had been carrying the light apparatus destined for Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse and its loss delayed the lighthouse’s completion as new orders had to be sent to London. In December, 1895, the foundation stone was laid at the site[xx]. However, the site was not as stable as first believed and no less than seven metres of earth had to be excavated to reach the solid bedrock below. The site then required approximately 420 cubic metres of concrete and 760 cubic metres of masonry to fill in the hole and serve as a suitable foundation[xxi]. Limestone for the 39-metre tower and four accompanying cottages was quarried locally.

Opening day for the Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse, on 10th December 1986, was a momentous event for the state of Western Australia. The premier dedicated the lighthouse to the mariners of the world and a time capsule was laid with the foundation stone which read:

Foundation Stone

Laid by Hon. Sir John Forrest KCMC

Premier of the Colony

13th December 1895

The Notice to Mariners on 10 December 1986 read:

The Marine Board has been notified that the new light at Cape Leeuwin (W.A) will be displayed on and after to-day. The light is a revolving one, of the Feux Eclairs, or lightning flash lights, type, and will show a single flash of white light for five seconds, duration of flash one-fifth seconds. The tower is cylindrical in form, 135ft in height from base to vane, and is of natural stone colour. The focal plane of the light is 185 ft above high water, and the light will be visible all round the horizon from a distance of 19 ¾ miles in clear weather. A subsidiary light formerly mentioned will not be exhibited. The approximate position of the new lighthouse is latitude 34deg 22min south, longitude 115deg 8min east. The necessity of exhibiting a light on the extreme point of Cape Leeuwin for the guidance of mariners has long been recognised by those trading around the Cape[xxii].

Equipment when built

Upon completion, the lighthouse, composed of a total of seven levels and stood 128 ft (39 m) tall. The tower base was more than two metres thick and a 176-step iron spiral staircase spanned six levels to the lantern room.

The original light source was a kerosene wick lamp using seven gallons of fuel a night. The Chance Brothers. first-order lens, rotating in a mercury bath[xxiii], produced 250,000 candelas, visible for 30 miles on a clear night. The red subsidiary light originally intended for the lighthouse was transferred to Bathurst Point Lighthouse, WA in 1900 after it was revealed Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse did not have a space built to accommodate it [xxiv].

Three keepers were stationed at the lighthouse.

Figure 12. Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse 1st Order Chance Brothers Lens. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia, NAA: A9568, 7/10/6 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

3.6 Lighthouse keepers

Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse was manned for nearly 100 years from 1896 until 1995. Initially, one chief lighthouse keeper and two assistant keepers were stationed at the site. The keepers and their families resided on-site in keepers quarters constructed at the same time as the lighthouse. At some point prior to 1908, a third cottage was built to house an additional assistant keeper brought on to relieve duties and cut firewood[xxv].

Of all the keepers stationed at Cape Leeuwin, Felix von Luckner proved infamous. Von Luckner briefly served as assistant keeper before joining the German navy. He went on to become a highly decorated German naval officer during World War I (1915-1918). Over the course of his navy career on the Seeadler, von Luckner captured 14 Allied ships without any casualties[xxvi].

3.7 Chronology of major events

The following table details the major events that occurred at Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse from its construction in 1895 to present day.

Date | Event Details |

13 December 1895 | Foundation stone laid by the premier of Western Australia.[xxvii] |

10 December 1896 | Lighthouse officially opened by Sir John Forrest.[xxviii] |

September 1905 | Governor-general and the state governor visit Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse.[xxix] |

1908 | Additional cottage constructed for an assistant lightkeeper. |

31 March 1910 | The steamer Pericles wrecked on the Cape. Lightkeepers lit kerosene lamps to guide life boats to shore. No fatalities recorded.[xxx] |

January 1913 | Lightkeepers awarded the Certificate of Merit for their actions following the wrecking of the Pericles.[xxxi] |

9 August 1916 | Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse transferred from the Western Australian government to the Commonwealth.[xxxii] |

July 1955 | Marine radio navigation beacon installed. |

1974 | Lighthouse painted white. The names of the stonemasons who participated in its construction were found cut into the stone. |

1975 | Auto alarm system installed, which reacted to radio frequency distress signals. |

1977 | Power house and transmitter building erected at Cape Leeuwin Lightstation. |

1980 | Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse listed on the Register of the National Estate. |

September 1992 | Lighthouse switched to automatic control. |

1995 | Lighthouse de-staffed. |

22 June 2004 | Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse listed on the Commonwealth Heritage List. |

13 May 2005 | Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse listed on the WA State Heritage Register. |

3.8 Changes and conservation over time

Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse has undergone a number of changes, both technological and physical, over the decades which have altered the lightstation.

The Brewis Report (1912)

Commander CRW Brewis, retired naval surveyor, was commissioned in 1911 by the Commonwealth Government to report on the condition of existing lights and to recommend any additional ones. Brewis visited every lighthouse in Australia between June and December 1912 and produced a series of reports published in their final form in March 1913. These reports were the basis for future decisions made in relation to the individual lighthouses, and capture a snapshot of the tower at that point in history.

Recommendations for Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse made by Brewis included alterations to the clockwork mechanism to increase the power of the light by 40 per cent, the repositioning of the weight tubes and removal of the fourth keeper.

Brewis Report: Cape Leeuwin Light[xxxiii] |

60 miles from Cape Naturaliste, 52 miles from D’Entrecasteaux Point. Lat. 34º 22’ S., Long. 115º 09’ E., Chart No’s. 413 and 1034. – Established 1896. Last altered 1908. Character: One white, dioptric, 1st Order (about 450,000 c.p.). Flashing, showing one flash of one-fifth second duration every five seconds. Illuminant, vapourized kerosene, 85 mm. mantle. Circular grey stone tower, 115 feet. Height of focal plane, 185 feet. Visibility: In clear weather, through an arc of about 240º from 261º (S. 86º W. Mag.) to 141º (S. 34º E. Mag.), for a distance of about 20 nautical miles. Optical Apparatus: Chance Bros., 1895. Two panels, each 122º horizontal angle. One complete revolution every ten seconds. Condition and State of Efficiency: This is no longer a signal station. A chain of reefs and islets extends from the shore, the outermost danger being the south-west breaker, on which the sea seldom breaks. It has 6 feet of water over it, and 10 fathoms around, and lies S. 25º E. Mag., nearly 5 miles from Cape Leeuwin. The Geographe Reef lies 8 miles N. 60º W. Mag. from Cape Leeuwin. Vessels must not approach within signalling distance. The tower, lantern, optical apparatus, and dwellings are in good condition. Four light-keepers are station here (one for cutting firewood and relieving duties). The fourth light-keeper is unnecessary. There are no signal duties, and no auxiliary lights. Firewood can be obtained in abundance, cut ready for use, at Flinders Bay, distant 2 ¼ miles. The duration of the flash is too short for practical purposes. To increase the duration of the flash, and preserve the present character of the light (flashing every five seconds), would necessitate a new optical apparatus. This would be unreasonable, considering the excellent condition and value of the present optical apparatus. To insert a third panel would be almost as costly as an undertaking. Small vessels in the heavy sea that is met with in this locality have the greatest difficulty, owing to the motion of the vessel, in obtaining a bearing of this light at night, on account of the shortness of the flash. The flash can be lengthened by increasing the period of the light to flashing every nine seconds, and increasing the diameter of the burner. The weight-tubes are not placed to the best advantage, and should be transposed on the next occasion that general repairs require to be carried out. Communication: By road to Flinders Bay, 2 ¼ miles. Connected by telephone with Busselton (distant 60 miles), Cape Naturaliste (distant 50 miles), and to main telegraph system. Provisions by coastal steamer every five or six weeks. Mails weekly, via Karridale Timber Company’s railway. Fogs: Fogs lasting from two to six hours have been recorded, occurring principally in the early morning, between November and March. Dense smoky haze and heavy mist are also experienced, particularly in the early morning. Soundings: Great attention should be paid to the caution on the Admiralty Chart. The use of lead should never be neglected. The soundings on the Chart are of a complete and suitable nature, and vessels, by maintaining a depth of over 40 fathoms, can assure their safety. This depth should leave a vessel at least 10 miles from the light, and well clear of all outlying dangers. RECOMMENDED: (a) The speed of the light be altered by (1) inserting new spur wheels in the clock; and (2) substituting for the present 85 mm. mantle an installation of three mantles, each 55 mm. This will increase the beam of the light, also the power of the light, by about 40 per cent, and produce a character of one flash of fully one-third second duration every nine seconds. Candle-power, about 630,000, Provided the use of the lead (an ordinary precaution in navigation) is never neglected, even though the light is in sight, this should provide adequately and efficiently for the purposes of navigation. (b) The weight-tubes be correctly placed. (c) One assistant light-keeper be withdrawn. |

Alterations to the Light

Changes to the light at Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse have occurred due to advances in technology. The table below lists the alterations made.

Date | Alteration |

1908 | Intensity increased to 450,000 cd. |

Pre—1912 | Red light (secondary light) discontinued. |

1925 | Kerosene lamp replaced by a pressurised kerosene incandescent-mantle system. Strength of main light increased from 450,000 to 784,000 candle power, with a visibility of 20 miles on clear nights. Speed of rotation of the lens reduced – flashing 7.5 secs with the length of the flash lasting 0.3 secs. |

14 June 1982 | Converted to mains electricity with standby diesel alternator, 1000W tungsten halogen lamps. Intensity: 1,000,000 cd. |

September 1992 | Light automated. |

2017 | Light source converted to LED. |

Conservation Works

The following tables lists the rectificaiton works undertaken to maintain the lighthouse.

Date | Works Completed |

2001 | Major works carried out: - Repair of corroded internal stairs

- Internal and external catwalk repainted

- Lantern room dome and gutter repainted

- Lantern room vents, internal catwalk and blocking plate skins removed and repaired

- Glazing leakage repaired

|

2010 | Major works carried out: - Paint removed from fifth and sixth floors

- Internal fittings stripped and repainted (sixth floor).

- Tower windows resealed (sixth floor).

- Internal paint removed (fourth floor)

- Two sets of stairs and decks repainted.

|

2011 | Major works carried out: - Internal walls and ceilings on ground, first and second floors stripped.

- Internal handrails painted (ground, first, second floors).

- Glass block windows replaced with polycarbonate clear windows with aluminium frames.

- Asbestos facia replaced with wood facia (battery room floor).

- Asbestos roof materials and debris replaced with colourbond roofing (battery room floor).

- Wind vane repaired and repainted.

- Battery room access doors repaired.

|

2015 | Major works carried out: |

2020 | Major works carried out: - Asbestos wall sheeting removed from oil store room.

- Oil store door replaced.

- Oil store roof repaired.

|

2021-2022 | Major works carried out: - Repainting of lighthouse.

- Repair and repointing of stonework.

- Repair of lantern room corrosion.

- Replacement of oil store roof, gutter and flashing.

- Repair of internal accessways.

|

3.9 Summary of current and former uses

From its construction in 1896, Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse has been used as a marine AtoN for mariners at sea. Its AtoN capability remains its primary use.

The Cape Leeuwin Lightstation has consistently maintained a popular standing as a tourism site. The keeper’s cottages are now used for a variety of uses:

• Keepers cottage 1: visitor information, gift shop and café

• Keepers cottage 2: interpretive centre

• Keepers cottage 3: caretaker’s living quarters

• Collection of buildings (1950s): education centre/ office, staffroom and store shed.

• Building (1970s): public toilets

3.10 Summary of past and present community associations

Aboriginal heritage significance

The cape has significant past, present and future significance for the Wardandi, part of the Noongar People. Further consultation with traditional stakeholders is required for a greater understanding of the past and present associations held across the region.

Local, National, and International associations

The area is frequented by local and incoming visitors due to its historical, mythological and aesthetic associations. The site’s popularity triggered the introduction of tours inside the lighthouse.

3.11 Unresolved questions or historical conflicts

Any historical conflicts or unresolved questions brought to light will be addressed here in future versions of this plan.

3.12 Recommendations for further research

Research on past lighthouse keepers of the Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse may be beneficial in determining the full extent of the social value placed on the site within the surrounding communities of the Cape. Additionally, archaeological investigation of the site may reveal further information on prehistoric and historic uses of Cape Leeuwin to broaden understandings of the site’s intrinsic value[xxxiv].

4. Fabric

4.1 Fabric register

The cultural significance of the lighthouse resides in its fabric and in its intangible aspects, such as the meanings people ascribe to it, and its connections to other places and things. The survival of its cultural value depends on an understanding of what is significant and on clear thinking about the consequences of change. The Burra Charter sets out good practice for conserving cultural significance.

Criteria listed under ‘Heritage Significance’ refer to the criteria satisfied within the specific Commonwealth heritage listing (see section 5.1).

Lighthouse Feature: Lantern roof

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

1896 Chance Bros part spherical dome of copper sheets lapped and screwed to ribs.

- Ribs – Chance Bros cast iron radial ribs.

- Inner skin – copper sheets screw fixed to ribs.

- Ventilator – drum type (wind vane and direction pointers removed, see Site – Wind Vane below).

- Gutter – circular ring of cast iron pieces bolted together.

- Handrails – one circular hand rail attached to lantern roof, another attached to top of ventilator drum. Curved iron ladder fixed to roof.

- Drip tray – copper dish suspended under ventilator.

- Heat tube support – framework with six radial members of rolled ferrous T-section, attached to gutter and to central ring. Heat tube and lens support still in place.

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The lantern roof is an original and essential part of a lighthouse associated with the development of coastal navigation in Australia (criterion a).

The lantern roof contributes to the aesthetic value of the lighthouse (criterion e).

Lighthouse Feature: Lantern glazing

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

1896 Chance Bros, cylindrical in form.

- Panes – curved rectangular glass, three tiers. Blank panes to landward side.

- Astragals – Chance Bros vertical and horizontal astragals of rectangular and triangular section iron, bolted to gutter ring at top, and to lantern base below.

- Ladder rail – attached to gutter.

- Downpipes – four copper downpipes discharging to balcony floor.

- Handholds – three cast metal handholds bolted to each vertical astragal, except where downpipes are/were fitted.

Finish | astragals and glazing strips painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service, reglaze as necessary, prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The lantern glazing is an original and essential part of a lighthouse associated with the development of coastal navigation in Australia (criterion a).

Lighthouse feature: Internal catwalk

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

Cast iron lattice floor panels supported on solid cast iron brackets bolted to the upper section of the lantern base.

- Ladder – fixed ladder with cast iron treads on wrought iron strings.

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The internal catwalk is an essential part of a lighthouse associated with the development of coastal navigation in Australia (criterion a).

Lighthouse feature: External catwalk

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

1896 Chance Bros, cast iron lattice floor panels supported on openwork cast iron brackets bolted to lantern base.

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The external catwalk is an original and essential part of a lighthouse associated with the development of coastal navigation in Australia (criterion a).

The external catwalk contributes to the aesthetic value of the lighthouse (criterion e).

Lighthouse feature: Lantern base

© AMSA 2020

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

1896 Chance Bros, cylindrical in form. Curved panels of cast iron fixed together.

- Internal lining – curved iron plates screwed to the outer cast iron panels.

- Vents – round external air inlets as part of wall panels. Large round copper alloy regulators below internal catwalk and small ones above.

- Door – iron framed and sheeted door hung on copper alloy hinges. Copper alloy mortise lock with copper alloy bar handles inside and out. Brass maker’s plate fixed to door.

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The lantern base is an original and essential part of a lighthouse associated with the development of coastal navigation in Australia (criterion a).

The lantern base contributes to the aesthetic value of the lighthouse (criterion e).

Lighthouse feature: Lantern floor

© AMSA 2020

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

1896 floor of cast iron plates supported on rolled iron I section beams built into the tower walls.

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The lantern floor is an original and essential part of a lighthouse associated with the development of coastal navigation in Australia (criterion a).

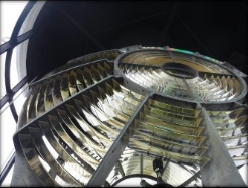

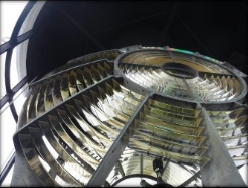

Lighthouse feature: Lens assembly

© AMSA 2020

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

1896 Chance Bros 920mm focal radius catadioptric rotating lens assembly of glass and gunmetal, rotating at 4 rpm. Gives two single flashes in each revolution.

- Bearing – 1896 Chance Bros mercury float, see pedestal below.

Cape Leeuwin lighthouse is one of six AMSA lighthouses still operating with a 1st order rotating lens and mercury float pedestal. The lantern, lens and pedestal all date from 1896, the earliest AMSA light with such an intact system.

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The lens assembly is an original and essential part of a lighthouse associated with the development of coastal navigation in Australia (criterion a).

The original 1896 1st Order Chance Bros lens assembly is one of only six still in operation (criterion b).

Lighthouse feature: Light source

© AMSA 2020

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

LED Array Sealite SL-LED-324-W. Installed 2017.

Condition | intact and sound |

Significance | low |

Maintenance | keep in service |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: Low

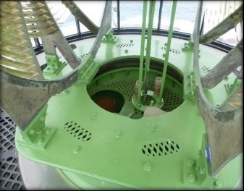

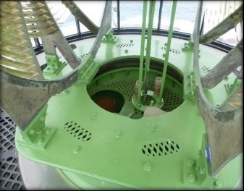

Lighthouse feature: Pedestal

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

1896 Chance Bros mercury float pedestal.

- Base – cast iron, in the form of a large cylinder in which the clock is mounted, with four large access openings.

- Mercury trough – cast iron circular trough mounted on top of the base. The mercury is still in place.

- Mercury float – cast iron annular float inside the trough.

- Lamp platform – cast iron platform with ribbed top surface.

- Lamp stand – three iron rod uprights, with later adaptor added on top to support the lamp changer.

- Drive – Chance Bros weight driven clock (disengaged). Two motor/gearbox units mounted on top of the clock, driving the original drive gears on the float. Housed inside the pedestal base, behind recent clear acrylic covers fitted to the openings in the base. One of the openings is fitted with recent plywood access door.

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The pedestal is an original and essential part of a lighthouse associated with the development of coastal navigation in Australia (criterion a).

The original 1896 Chance Bros mercury float pedestal is one of only six still in operation (criterion b).

Lighthouse feature: Balcony floor

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

1896 stone slab floor, supported on the cornice and top of the tower wall.

Finish | painted with resilient grey coating |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service maintain seal joints prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The balcony floor is an original and essential part of a lighthouse associated with the development of coastal navigation in Australia (criterion a).

Lighthouse feature: Balcony balustrade

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

1896 Chance Bros cast iron balusters with four iron pipe rails. Recent expanded aluminium mesh grille with extruded aluminium frame.

Finish | iron parts: painted aluminium: unpainted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | recent mesh grille: low all other fabric: high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare at normal intervals |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The balcony balustrade is an original and essential part of a lighthouse associated with the development of coastal navigation in Australia (criterion a).

Lighthouse feature: Walls

© AMSA 2020

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

1896 walls of stone masonry, rock faced with chiselled dressings outside, chiselled inside.

Finish | external: painted internal: bare stone |

Condition | Heavy mould on internal walls in upper part of tower, some mould on external walls, pointing deteriorating in some internal locations. Otherwise intact and sound. |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | Keep in service, monitor condition of pointing and stonework repair pointing as required. Prepare and repaint external surfaces at regular intervals. Treat mould on internal walls |

Rectification works | implement moisture controls |

Heritage significance: High

The tower walls are an original and essential part of a lighthouse associated with the development of coastal navigation in Australia (criterion a).

The painted, rock-faced tower walls contribute to the aesthetic values of the lighthouse (criterion e).

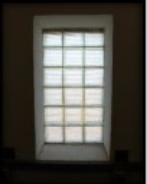

Lighthouse feature: Windows

© AMSA 2020

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

1896 window openings with later stainless steel framed fixed glass or glass brick infill.

- External grilles – recent stainless steel fixed grilles on ground level windows.

Finish | unpainted |

Condition | sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | original openings: high recent stainless steel and glass: low |

Maintenance | keep in service |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The windows are an original and essential part of a lighthouse associated with the development of coastal navigation in Australia (criterion a).

The windows contribute to the aesthetic value of the lighthouse (criterion e).

Lighthouse feature: Staircase screen and cupboard

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

- 1896 semi-circular wall enclosing the stairwell where it arrives at the service room floor (the fifth floor), timber framed and panelled

- Timber ceiling

- Attached timber cupboard with two panelled doors. Later sheeting and electrical equipment attached facing centre of the tower.

- Cast iron brackets bolted to tower walls support the ceiling (and originally the rainwater tank, now removed).

Finish | stained/varnished |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The staircase screen and cupboard are original and essential parts of a lighthouse associated with the development of coastal navigation in Australia (criterion a).

Lighthouse feature: Doors

© AMSA 2020

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

Timber framed and sheeted doors in timber frames to the tower entrance and to the oil store entrance. Each opening has a timber frame with arched head and a pair of door leaves hung on butt hinges. Tower entrance door has a cylinder dead-locking rim-lock.

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The tower doors are an essential part of a lighthouse associated with the development of coastal navigation in Australia (criterion a).

Lighthouse feature: Intermediate floors

© AMSA 2020

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

Five intermediate floors of 1896 iron checker plate on rolled iron I section beams built into tower walls.

- Balustrade – continuous with iron stair balustrade, with extended height railing of steel flat and pipe sections.

Finish | painted |

Condition | Corrosion on edges of floor plates and supporting beams where they intersect with masonry wall. Otherwise intact and sound. |

Integrity | high |

Significance | extended balustrade: low other parts: high |

Maintenance | keep in service treat corrosion prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The intermediate floors are an original and essential part of a lighthouse associated with the development of coastal navigation in Australia (criterion a).

Lighthouse feature: Stairs

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

1896 geometric stair with cast iron treads bolted to curved iron strings. Wrought iron handrail and stanchions.

Finish | painted |

Condition | localised corrosion on external stair stringers and wall anchor bolts otherwise intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The internal stairs are an original and essential part of a lighthouse associated with the development of coastal navigation in Australia (criterion a).

Lighthouse feature: Ground floor

©AMSA 2020

©AMSA 2020

Description and condition

1896 concrete slab on ground.

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The ground floor is an original and essential part of a lighthouse associated with the development of coastal navigation in Australia (criterion a).

Lighthouse feature: Weight tube

© AMSA 2020

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

1896 riveted iron tube in the centre of the tower, between the lantern floor and the ground floor.

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | preserve prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The weight tube is an original and essential part of a lighthouse associated with the development of coastal navigation in Australia (critieron a).

Lighthouse feature: Oil store

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

1896 stone single-storey room attached to the base of the tower. Later timber framed hipped

roof with steel sheet roof, eaves and gutter. Ceilings and walls lined with sheet material. Concrete floor.

- Equipment – backup power supply, automatic identification system and associated control equipment

Finish | painted |

Condition | intact and sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | keep in service prepare and repaint at normal intervals |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The oil store is an original and essential part of a lighthouse associated with the development of coastal navigation in Australia (criterion a).

The oil store maintains principal characteristics of late nineteenth century lighthouse complexes (criterion d).

The low height of the oil store contributes to the aesthetic value of the lighthouse (criterion e).

Lighthouse feature: Wind vane

© AMSA 2020

© AMSA 2020

Description and condition

1896 Chance Bros wind vane and cardinal pointers, removed from the lantern roof and installed on a steel post near the base of the tower (outside AMSA area).

Condition | sound |

Integrity | medium |

Significance | high |

Maintenance | monitor as necessary |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: High

The original Chance Bros wind vane contributes to the aesthetic value of the lighthouse (criterion e).

Lighthouse feature: Apron paving

Description and condition

Asphalt paving around the tower and oil store, with concrete kerb at margin.

Finish | asphalt |

Condition | sound |

Integrity | high |

Significance | low |

Maintenance | inspect monitor cracks and repair if necessary |

Rectification works | none |

Heritage significance: Low

4.2 Related object and associated AMSA artefacts

There are no AMSA artefacts currently stored at Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse.

An exhibition showcasing a collection of artefacts is located within the larger lightstation and overseen by the tourist operators.

4.3 Comparative analysis

Figure 13. View of Wadjemup (Rottnest Island) Lighthouse (© AMSA, 2017)

Figure 14. View of Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse (© AMSA, 2010)

Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse bears significant resemblance to the Wadjemup (Rottnest Island) Lighthouse located off the west coast of the state. Originally built in 1851, Wadjemup Lighthouse was replaced in 1896, the same year Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse was constructed. Both lighthouses were designed by WT Douglass and constructed from locally-quarried limestone (see Figure 15). Wadjemup stands at 38 metres high and Cape Leeuwin is 39 metres. Both Wadjemup Lighthouse, installed with a 1st Order eight panel lens, and Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse, installed with a 1st Order bi-valve lens, continue to operate on a mercury bath pedestal.

Figure 15. Wadjemup (Rottnest Island) Lighthouse drawing 1884-85. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia, NAA: K1372, WN/01/014/01 (© Commonwealth of Australia, National Archives of Australia)

5. Heritage Significance

5.1 Commonwealth heritage list – Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse

Statement of Commonwealth heritage significance

The following information is taken from the Cape Leeuwin Lightstation listing on the Australian Heritage Database (Place ID: 105416).

Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse, completed in 1896, is important in illustrating the development of coastal navigation in Australia and the evolution of lighthouse design following the inter-colonial conference of 1873 in Sydney which resulted in an agreed series of decisions which would result in a rough national chain of navigational aids. The lighthouse had two functions; to mark the coastal route to Perth via Albany and as the first landfall for vessels crossing the Indian Ocean to Australia. The upgrading of the lighthouse in 1925 under the Commonwealth illustrates the increasing importance of coastal shipping in Australia (Criterion A) (Australian Historic Themes: 3.8 Moving goods and people)

Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse is exceptionally important in demonstrating in its original lens array and rotation mechanism the earliest use of the mercury bath system in Australia (Criterion B).

In conjunction with the Keepers Cottages (separately listed at File No. 5/2/40/4) the Lighthouse is important in illustrating the principal characteristics of late nineteenth century lighthouse complexes in remote coastal areas (Criterion D).

The lighthouse, situated on a narrow, sparsely vegetated strip of land and surrounded by sea on three sides, is significant as a prominent landmark feature on the coast of Western Australia (WA). The height of the lighthouse also makes it an outstanding landmark from the land and in particular from the approach road from Augusta (Criterion E).

The area has known Indigenous heritage values. The Australian Heritage Commission has not yet assessed the national estate significance of these values.

Commonwealth heritage values – criteria

There are nine criteria for inclusion in the Commonwealth Heritage List – meeting any one of these is sufficient for listing a place. These criteria are similar to those used in other Commonwealth, state and local heritage legislation, although thresholds differ. In the following sections, the Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse is discussed in relation to each of the criteria as based on the site’s current Commonwealth Heritage Listing (Place ID 105416).

Criterion | Relevant attributes identified | Explanation |

Criterion A – Processes This criterion is satisfied by places that have significant heritage value because of [their] importance in the course, or pattern, of Australia’s natural or cultural history. | All of the fabric of the lightstation including the tower, keepers' cottages, ancillary buildings and site layout. | Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse, completed in 1896, is important in illustrating the development of coastal navigation in Australia and the evolution of lighthouse design following the inter-colonial conference of 1873 in Sydney, which resulted in an agreed series of decisions which would result in a rough national chain of navigational aids. The lighthouse had two functions; to mark the coastal route to Perth via Albany and as the first landfall for vessels crossing the Indian Ocean to Australia. The upgrading of the lighthouse in 1925 under the Commonwealth illustrates the increasing importance of coastal shipping in Australia. |

Criterion B – Rarity This criterion is satisfied by places that have significant heritage value because of [their] possession of uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of Australia’s natural or cultural history. | Evidence of the original lens array and rotation mechanism | Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse is exceptionally important in demonstrating in its original lens array and rotation mechanism the earliest use of the mercury bath system in Australia. |

Criterion D – Typicality This criterion is satisfied by places that have significant heritage values because of [their] importance in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of Australia’s natural or cultural history. | All the nineteenth century buildings and layout of the complex | In conjunction with the keepers cottages, the lighthouse is important in illustrating the principal characteristics of late nineteenth century lighthouse complexes in remote coastal areas. |

Criterion E – Aesthetic characteristics This criterion is satisfied by places that have significant heritage value because of [their] importance in exhibiting particular aesthetic characteristics values by a community or cultural group. | The height of the lighthouse, its prominent location, low height of surrounding heath and relatively low height of ancillary structures. | The lighthouse, situated on a narrow, sparsely vegetated strip of land and surrounded by sea on three sides, is significant as a prominent landmark feature on the coast of Western Australia (WA). The height of the lighthouse also makes it an outstanding landmark from the land and in particular from the approach road from Augusta. |

5.2 WA State heritage register – Cape Leeuwin Lightstation

The following statement of significance and criterion information is taken from the Cape Leeuwin listing on the WA Heritage Register (Place ID: 00104).

WA State heritage – statement of significance

Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse and Quarters, a small precinct which contains a stone lighthouse, keepers’ quarters (stone) and various service buildings, has cultural heritage significance for the following reasons:

the place is part of a system of coastal lights that was developed at the end of the nineteenth century by the various Australian colonies to improve the safety to shipping operating in Australian territorial waters. Although recognised as being of major importance to the eastern colonies, it was fully funded by the state government of Western Australia and the fourth coastal lighthouse constructed by the state government;

the place, in particular the lighthouse, has retained a high degree of authenticity and integrity;

the place has aesthetic value both in its design and as a striking landmark on Cape Leeuwin;

the place was historically important to the local timber industry which relied on small ships to transport the timber to other ports. As Cape Leeuwin could be treacherous in bad weather, the light was a valuable navigational aide;

the place represents a way of life that is no longer practised in Western Australia and one which is rapidly becoming scarce in other parts of Australia and the world;

the place has strong associations with John Forrest who tried for many years to establish a new light near Cape Leeuwin; with M.C. Davies, an important entrepreneur in Augusta, who pushed for a light on Cape Leeuwin and George Temple Poole who supervised the construction of the light and was responsible for the design of the keepers’ quarters;

the place is socially important to the people of Augusta-Margaret River for its tourist potential; the place has the potential to reveal archaeological evidence about how people lived in isolated conditions;

the lighthouse is a fine example of the type of stone towers erected during the nineteenth century to house lights; and

the place at one time had the most powerful lamps in Australia and it was also the last to receive a modern tungsten lamp.

While the new service buildings on the western side of the cottages are considered to have some historic importance, they are architecturally intrusive and are assessed as having low significance.

WA State Heritage Criteria

WA State Heritage Register Criterion (SHR) | Explanation/evidence |

SHR Criterion 1 – Aesthetic value | Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse is a striking feature which rises dramatically upwards in a landscape that is essentially barren and comparatively flat. The slender tower is visible at the point of Cape Leeuwin long before any other buildings come into focus and appears to stand as an exclamation point in the centre of the narrow strip of land which is Cape Leeuwin. (Criterion 1.3) Due to the general topography of Cape Leeuwin, it was not possible to place the keepers' cottages in a sheltered position. Thus, the whole precinct is very exposed to both the weather and the observer's eye. When the entire precinct is viewed from the north, the quarters and service buildings, which in themselves do not have any aesthetic value, assist inleading the eye along to the tall, stately form of the lighthouse at the south. (Criterion 1.4) The steep pitch of the cottage roofs and the enclosure of the verandahs, has given the residences a lumbering presence which contrasts with the delicate spire of the lighthouse tower and the rounded forms of the natural landscape. (Criterion 1.4) |