Commonwealth of Australia

Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999

Subsection 269A(3)

Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (Recovery Plan—Botaurus poiciloptilus) Instrument 2023

We, Tanya Plibersek, Minister for the Environment and Water (Commonwealth); Reece Whitby, Minister for Environment (State of Western Australia); David Speirs, Minister for Environment and Water (State of South Australia); Lily D’Ambrosio, Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change (State of Victoria); and Meaghan Scanlon, Minister for the Environment and the Great Barrier Reef (State of Queensland) under subsection 269A(3) of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth), jointly make a recovery plan titled:

National Recovery Plan for the Australasian Bittern (Botaurus poiciloptilus), Commonwealth of Australia 2022

The recovery plan will come into force on the day after the plan is registered on the Federal Register of Legislation.

Dated this 5th day of February 2023

Tanya Plibersek

Tanya Plibersek

Minister for the Environment and Water (Commonwealth)

Dated this 8 day of March 2022

Reece Whitby

Reece Whitby

Minister for Environment (Western Australia)

Dated this 16 day of April 2021

David Speirs

David Speirs

Minister for Environment and Water (South Australia)

Dated this 31st day of December 2021

Lily D’Ambrosio

Lily D’Ambrosio

Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change (Victoria)

Dated this 13 day of June 2022

Meaghan Scanlon

Meaghan Scanlon

Minister for the Environment and Great Barrier Reef (Queensland)

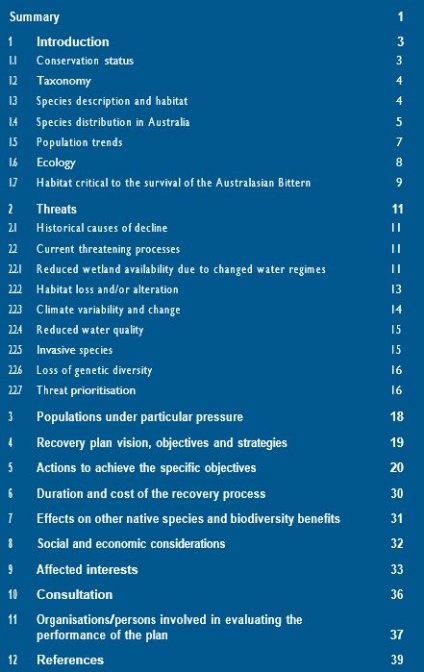

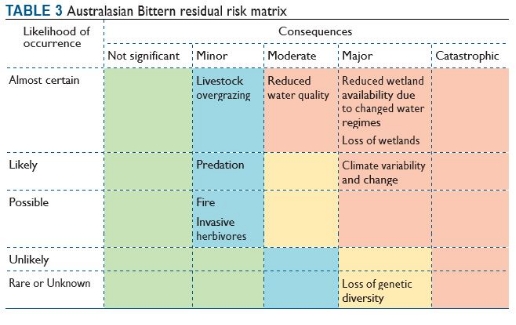

Contents

Australasian Bittern (Botaurus poiciloptilus)

Family: Ardeidae

Current status of taxon:

• Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cwlth): Endangered

• Nature Conservation (Wildlife) Regulation 2006 (Queensland): Endangered

• Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (New South Wales): Endangered

• Nature Conservation Act 2014 (Australian Capital Territory): Endangered

• Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (Victoria): Critically Endangered

• National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 (South Australia): Vulnerable

• Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (Western Australia): Endangered

• IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Endangered

Distribution and habitat:

In addition to Australia, the Australasian Bittern occurs in New Zealand and New Caledonia. In Australia, Australasian Bitterns can be divided into two subpopulations, the south eastern and south western subpopulations. The species occurs discontinuously along the east coast from south east Queensland to south east South Australia and Tasmania, extending into the Murray–Darling Basin. In Western Australia, it is presently confined to widely separated parts of the south western and south eastern coast and a small number of wetlands farther inland. Breeding of both subpopulations occurs at both coastal and inland sites. The Australasian Bittern preferred habitat comprises wetlands with dense vegetation from 0.5–3.5 metres in height, where it forages in still, shallow water up to 0.3 m deep, often at the edges of pools or waterways, or from platforms or mats of vegetation over deep water. It favours permanent and seasonal freshwater habitats, particularly those dominated by sedges, rushes and reeds, as well as rice crops.

Recovery plan vision, objective, and strategies:

Long-term vision

The Australasian Bittern population has increased in size to such an extent that the species no longer qualifies for listing as threatened under any of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 listing criteria.

Recovery plan objective:

The objective of this recovery plan is to demonstrate, by 2032, an increasing trend (compared to 2020 baseline counts) in the number of mature individuals being recorded in annual surveys at key locations, and to ensure that habitat critical to the survival of the Australasian Bittern is protected and managed to meet the ecological requirements of the species.

Strategies to achieve objectives

1 Implement management actions that mitigate or reduce threats to Australasian Bittern and their habitat

2 Enhance the quality, extent and protection of suitable habitat for the Australasian Bittern

3 Undertake research and monitoring to improve knowledge of the biology, ecology and population trends of Australasian Bittern

4 Increase stakeholder participation in Australasian Bittern conservation and management

5 Coordinate, review and report on recovery progress

Criteria for success:

This recovery plan will be deemed successful if, by 2032, all the following have been achieved:

• The relative abundance of Australasian Bittern has increased from 2020 baseline counts as a result of recovery actions

• The number of occupied sites supporting Australasian Bittern has increased from 2020 baseline counts, and the quality of the sites has improved, as measured against a range of environmental health indicators

• Research and monitoring of movement patterns and habitat use have increased understanding of the species ecology and information has been used to improve management actions for the species

• There is increased participation by key stakeholders and the public in recovery efforts and monitoring

Recovery team:

Recovery teams provide advice and assist in coordinating actions described in recovery plans. They include representatives from organisations with a direct interest in the recovery of the species, including those involved in funding and those participating in actions that support the recovery of the species. The national Australasian Bittern Recovery Team has the responsibility of providing advice, coordinating and directing the implementation of the recovery actions outlined in this recovery plan. The membership of the national Recovery Team includes individuals from relevant government agencies, non-government organisations and expertise from independent researchers and community groups.

Chapter 1

Introduction

This document constitutes the ‘National Recovery Plan for Australasian Bittern (Botaurus poiciloptilus)’. The plan considers the conservation requirements of the species across the part of its range lying within Australia and identifies the actions to be taken to ensure the species’ long-term viability in nature, and the parties that will undertake those actions.

Principal threats to the Australasian Bittern include the loss and degradation of wetland habitats through altered water regimes (e.g. drainage and diversion, infilling, water regulation), clearing for urban and agricultural development and climate change. Other potential threats to the species may include reduced water quality, predation by introduced foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and cats (Felis catus), overgrazing by livestock, and inappropriate fire regimes.

Accompanying Species Profile and Threats Database (SPRAT) pages provide background information on the biology, population status and threats to the ‘species’. SPRAT pages are available from: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl.

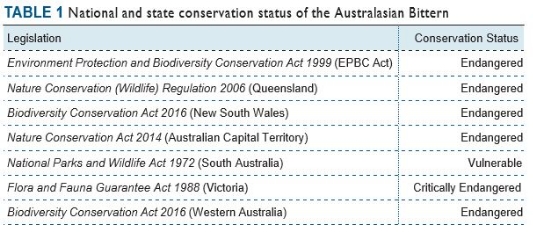

1.1 Conservation status

The Australasian Bittern is a listed threatened species under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). The species is also listed as threatened under State Legislation (Table 1).

The species was included in the Endangered category of the EPBC Act in 2011 as the estimated total number of mature individuals of the species was low and evidence suggested that the number would continue to decline at a high rate. The species was also suspected to have undergone a severe reduction in population numbers as a result of the reduction in the species’ area of occupancy and the loss of habitat and breeding grounds (TSSC 2011). There has been no change in the population trajectory since 2011 and the species continues to meet the Endangered category (Herring et al. 2021).

1.2 Taxonomy

Conventionally accepted as Botaurus poiciloptilus (Wagler, 1827). No subspecies have been described. The species is commonly known as the Australasian Bittern. It is also known as the Boomer, Bullhead, Bunyip, Black-backed or Brown Bittern.

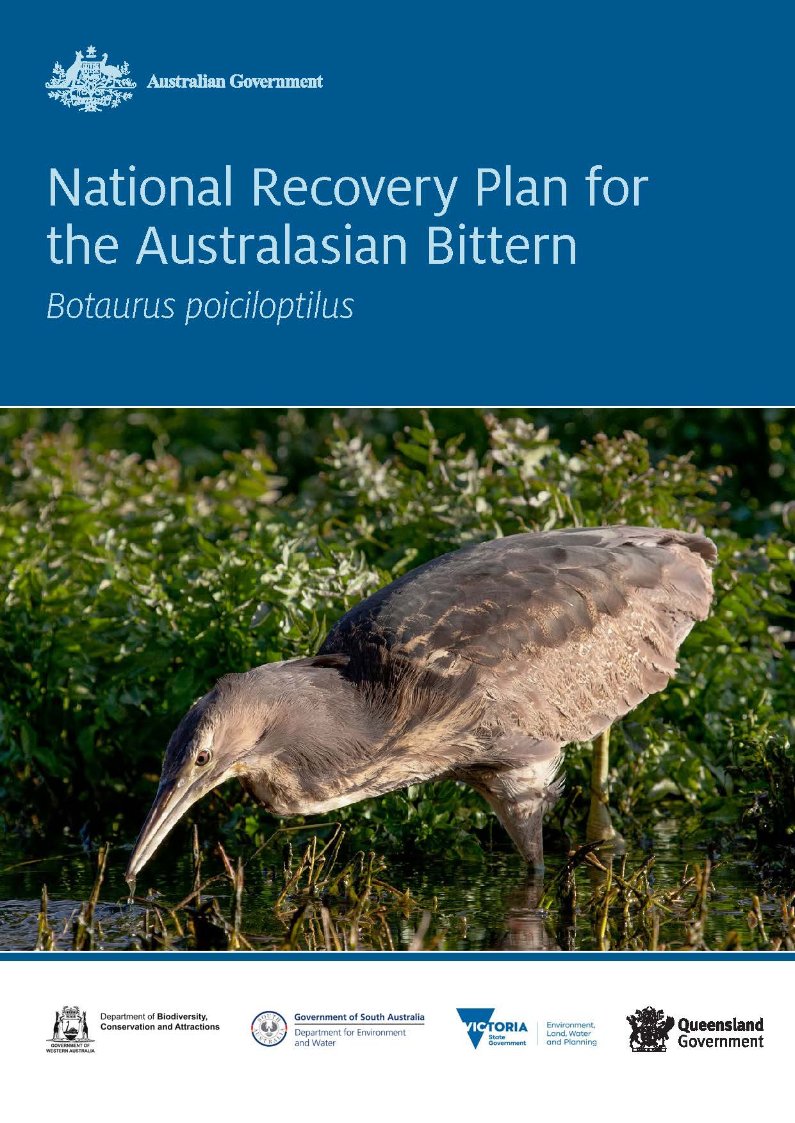

1.3 Species description and habitat

Australasian Bitterns are large, stocky, thick–necked, heron–like birds. The species grows to a length of 66–76 cm and has a wingspan of 1,050–1,180 mm. The average male weighs approximately 1,400 g and the average female weighs approximately 900 g (Marchant and Higgins 1990). The upper-parts of the body are brown and dark brown to black, mottled and buff, in complex patterns that aid the bird’s concealment in swamp vegetation. The under-parts of the body are streaked and scalloped, brown and buff. The species has a prominent black–brown stripe running down the side of the neck, the eyebrow is pale, and the chin and upper throat are white. The bill is straight, pointed and straw yellow to buff in colour with a dark grey ridge. The legs and feet are pale green to olive and the eyes are orange–brown or yellow (Marchant and Higgins 1990; Pizzey and Knight 1997). Darker and paler variants of the plumage have been observed in adults. Juveniles are generally paler than adults and have heavier buff flecking on the back (Marchant and Higgins 1990; Pizzey and Knight 1997).

Australasian Bitterns occur mainly in freshwater wetlands in the temperate southeast and southwest of Australia and, exceptionally, in estuaries or tidal wetlands (Marchant and Higgins 1990). Australasian Bitterns’ preferred habitat comprises wetlands with dense vegetation, especially where there is a mosaic of cover, from 0.5–3.5 metres in height, where they forage in still, shallow water up to 0.3 m deep, often at the edges of pools or waterways, or from platforms or mats of vegetation over deep water. They favour permanent and seasonal freshwater habitats, particularly those dominated by sedges, rushes and/or reeds (e.g. Phragmites, Cyperus, Eleocharis, Juncus, Typha, Baumea, Bolboschoenus) or cutting grass (Gahnia) growing over a muddy or peaty substrate, as well as rice crops (Marchant and Higgins 1990). In south-western Australia the species also occurs in wetlands where thickets of wetland shrubs (e.g. Melaleuca, Agonis spp.) provide patches of tall cover within sedge-dominated habitat. In the Murray–Darling Basin, Australasian Bitterns occur in floodplain swamps that may include lignum (Duma florulenta) shrubs within sedge or reed beds as well as in commercial rice-fields (NSW Riverina). Despite occurring in a range of wetland types, breeding is known to occur in a much smaller sub-set of locations.

1.4 Species distribution in Australia

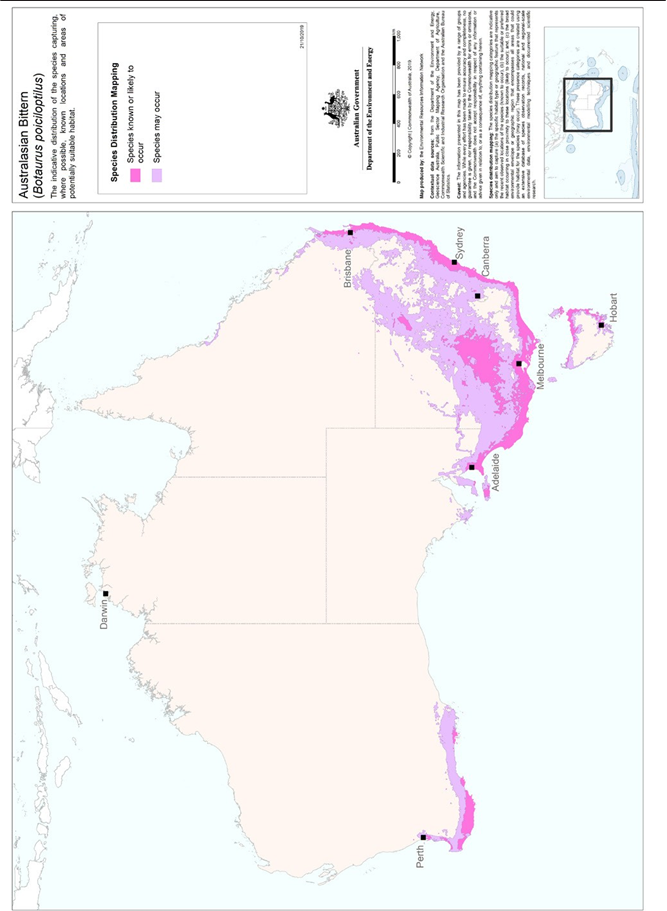

In Australia, the Australasian Bittern occurs from south-east Queensland to south-east South Australia as far as the Adelaide Region, southern Eyre Peninsula, Tasmania and in the southwest of Western Australia (Jaensch et al. 1988; Marchant and Higgins 1990; Garnett et al. 2011; Figure 1). Vagrants have also been recorded from northern Australia, including one record from Argyle Downs in the extreme north east of Western Australia (Marchant and Higgins 1990). Due to geographical isolation over 1,500 km of mainland without suitable habitat, the population can be divided into two subpopulations, the south-eastern and south-western subpopulations. The Australasian Bittern also occurs in New Zealand and New Caledonia (Marchant and Higgins 1990).

In Queensland, the species occurs as far north as Yeppoon and west to Wyandra. In the south-east there is habitat remaining on Fraser Island, the Fraser Coast, North Stradbroke Island, Redlands and out into the Lockyer Valley. Key areas in Queensland where the species has been reliably seen in the past include the flood plains south of Byfield State Forest, Garnett's Lagoon, Bribie Island and Lake Clarendon.

In New South Wales, it occurs along the coast and is also frequently recorded in the Murray–Darling Basin, notably in floodplain wetlands of the Murray, Murrumbidgee, Lachlan, Macquarie and Gwydir Rivers.

In Victoria, it is recorded mostly in the southern coastal areas and in the Murray River region of central northern Victoria. The Barmah-Millewa Ramsar wetland complex is considered Australia’s most important site, with up to 73 booming males (Herring et al. 2019a).

In Tasmania, the species was formerly more widespread, however it is now absent from some major wetlands that have dried out (Marchant and Higgins 1990; Garnett and Crowley 2000). It occurs most commonly in the coastal regions in the north east, the east coast and on the islands of Bass Strait. Egg Islands has been identified as a Key Biodiversity Area for Australasian Bittern. The species also commonly occurs in the upper Derwent River estuary and Lakes Crescent and Sorell in central Tasmania (R. Gaffney pers. comm. 2018). Contemporary, distribution and population data from Tasmania is required to inform future management and recovery actions.

In South Australia, it primarily occurs in the south-east, ranging north to the

Murray River corridor and the Adelaide region, and west to the southern Eyre Peninsula and Kangaroo Island.

In Western Australia, the Australasian Bittern was formerly widespread in the south-west, ranging north to Moora, east to near Cape Arid, and inland possibly as far as the Toolibin Lake area (Jaensch et al. 1988). However, following extensive loss of habitat throughout the 1900s (e.g. due to drainage, salinization and ongoing urban development) the species is rarely recorded on the Swan coastal plain between Lancelin and Busselton. The species is however recorded more regularly in the southern coastal region from Augusta to the east of Albany and inland to some wetlands in the Jarrah forest belt (Lake Muir district), with small, isolated populations in swamps near Esperance eastwards to near Cape Arid (Jaensch et al. 1988; DBCA 2018).

1.5 Population trends

The estimated number of mature individuals is <2,000 globally with approximately 1,300 (range 750–1,800) in Australia (Herring et al. 2019a). This estimate includes combining mid-range figures for the Riverina rice field population estimate (500–1000, 750; Herring et al. 2019a) and the remaining Australian population estimate (247–796, 522; Garnett et al. 2011), with New Zealand (580–725, 626; Heather and Robertson 2000) and New Caledonia (0–50, 25; Martínez- Vilalta et al. 2019a).

Herring et al. (2019a) demonstrated that the rice fields of the Riverina support the largest known population of Australasian Bittern. Occupancy modelling from 2013–2017 in the Riverina region of New South Wales produced estimates of 368–409 for “early permanent water” rice crops in the Murrumbidgee and Coleambally Irrigation Areas (Herring et al. 2019a). Conservative estimates for “delayed permanent water” crops and for the unsurveyed Murray Irrigation Area suggest the Riverina’s rice fields support 500–1000 mature Australasian Bitterns in most years, representing about 59 per cent of the national population (Herring et al. 2019a).

Previous estimates in The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2010 (Garnett et al. 2011), which did not account for the Riverina population, suggested there were less than 1,000 mature Australasian Bitterns within the Australian population, and that the population was likely still decreasing. Based on two years of surveys at all wetlands where Australasian Bitterns had been reported between 1998 and 2008, BirdLife Australia estimated the number of adult birds in 2009–2010 to be 3–16 in Queensland, 82–162 in New South Wales, 86–248 in Victoria, 12–100 in Tasmania, 26–116 in South Australia and 38–154 in Western Australia – a national total of 247–796 (Birds Australia 2010; Garnett et al. 2011). The Western Australian population is now considered to comprise fewer than 100 individuals (Pickering 2012; DBCA 2018), while Tasmania is now thought to support 20–80 birds (E. Znidersic, unpublished).

Based on the published data, decreases in this species have been occurring for several decades. The reporting rate in national Atlas surveys has decreased from being recorded in 260 10-minute grid squares in 1977–1981, to 142 squares in 1998–2003, and 61 in 2003–2008 (Birds Australia 2010; Garnett et al. 2011). The reporting rate declined by >90 per cent in Tasmania and Western Australia, and by 63 per cent in the Riverina. The long-term rate of decline is estimated to be 20–30 per cent over two generations (11 years).

The area of occupancy of the Australasian Bittern in Australia is thought to have declined by 70 per cent between 1977 and 2008. These declines are considered to have led to a comparable decline in the size of the adult population.

Population estimates are largely based on skewed citizen science records and there is a degree of uncertainty of population trends across the range of the Australasian Bittern. Further complicating the matter is the level of mis-identification inherent in Australasian Bittern records. Immature Nankeen Night Herons (Nycticorax caledonicus) and Australian Little Bittern (Ixobrychus dubius) can be mistaken for Australasian Bittern by inexperienced observers.

1.6 Ecology

The knowledge base on Australasian Bittern is relatively weak and based on a small number of localised studies or observations, consistent with the secretive nature of the species and difficulty for researchers in accessing its preferred dense, swampy

habitats. Concerted programs of observation by BirdLife Australia and some government agencies in the past two decades have improved knowledge of occurrence and numbers (Herring et al. 2016, 2019)

The Australasian Bittern occurs solitarily, in pairs or dispersed aggregations of up to 34 birds (M. Herring, pers. comm. 2019). It is likely to be sedentary in permanent habitats, but regular post-breeding dispersal of between 400–600 km from inland rice fields to coastal wetlands has been recorded in south-eastern Australia (Herring et al. 2016; Bitterns in Rice Project, 2019).

The Australasian Bittern breeds from October to February in solitary pairs, or polygamously with up to three nesting females per booming male (Bitterns in Rice Project 2016). The species nests in densely vegetated freshwater wetlands, building its nests within dense cover over shallow water placed about 30 cm above the water level (Marchant and Higgins 1990). In rushland, it may avoid breeding in the densest areas (Marchant and Higgins 1990), and in reedbeds may prefer smaller patches, rather than continuous stands (M. Herring, pers. comm. 2019). If population densities are high, it may resort to more open wetlands for nesting, such as in stunted Acacia swamps (Marchant and Higgins 1990). Clutch size is usually four or five, but ranges from three to six (Serventy and Whittell 1976; Marchant and Higgins 1990).

The Australasian Bittern appears to be capable of moving between habitats as suitability changes. It can occur in high densities in temporary or infrequently filled wetlands during exceptionally wet years, and will also use ephemeral wetlands when moving from areas that are drying out (Garnett et al. 2011). Monitoring data provides evidence of seasonal movements and that they respond to favourable conditions at key wetlands. Analysis of data collected at regularly monitored wetlands in the Melbourne area (monthly surveys) shows an influx of birds during the non-breeding season between April and October, with a peak numbers in August (Kingsford et al. 2014). Between 2015–2018, satellite tracking demonstrated that birds move between the Murray Darling Basin and coastal South Australia, Victoria and New South Wales, so the winter influx around Melbourne is likely to be of birds which breed in the Riverina region (Bitterns in Rice 2019). The mobility of Australasian Bitterns makes the species hard to census as there is a risk of double counting birds recorded at different wetlands.

Based on occupancy modelling of the rice fields in southern New South Wales, and in the absence of similar work in other locations, rice fields are now known to support about 39 per cent of the total global population and 59 per cent of the Australian population (Herring et al. 2019a). These agricultural wetlands are typically flooded from October-April, with Australasian Bitterns commencing nesting in December and January when there is sufficient cover and prey. Rice height is a maximum of around 1.1 m, with water depths usually 15–25 cm. The most important prey for Australasian Bitterns in rice fields is tadpoles, frogs, fish and dragonfly larvae. In “early permanent water” crops, ponding is consistent from October-April, and potential fledging of all chicks prior to harvest is the norm, however a contraction of the ponding period – “delayed permanent water” – shorter season varieties and mid-season drainage are agronomic trends likely to reduce opportunities for successful breeding.

Rice fields are a seasonal attraction and Australasian Bitterns make widespread use of the surrounding irrigation infrastructure, such as vegetated channels and recycle dams, particularly between rice growing seasons (M. Herring, pers. comm.

2019). Reduced water allocations associated with drought, the trend towards cotton and other alternative irrigation water uses that do not support bitterns, and a shift away from “early permanent water” rice crops, which are favoured by Australasian Bitterns, suggests a decline in the rice field population is likely (Herring et al. 2019a).

There is very little data available but age of maturity of the Australasian Bittern is estimated to be one year and the life expectancy is estimated to be 11 years. These figures are based on figures for Eurasian Bittern (Botaurus stellaris). The generation length for the species is estimated to be 5.5 years (BirdLife International 2019).

1.7 Habitat critical to the survival of the Australasian Bittern

As noted above, the habitat, or biophysical environment, of the Australasian Bittern varies across its range, so it is not possible to generate one detailed description or definition of habitat critical to survival. The habitat critical to the survival of the Australasian Bittern may be more usefully defined at a bioregional scale that considers the combination of plants, animals, water depth, geology, landforms, and climate that is relevant to a geographical unit.

In general, Australasian Bitterns occur mainly in freshwater wetlands in the temperate southeast and southwest of Australia and, exceptionally, in estuaries or tidal wetlands (Marchant and Higgins 1990; Figure 1). Australasian Bitterns’ preferred habitat comprises wetlands with dense vegetation, especially where there is a mosaic of cover, from 0.5–3.5 metres in height, where they forage in still, shallow water up to 0.3 m deep, often at the edges of pools or waterways, or from platforms or mats of vegetation over deep water. They favour freshwater habitats with permanent or seasonal water, particularly those dominated by sedges, rushes and/or reeds (e.g. Phragmites, Cyperus, Eleocharis, Juncus, Typha, Baumea, Bolboschoenus) or cutting grass (Gahnia) growing over a muddy or peaty substrate (Marchant and Higgins 1990). In south-western Australia the species also occurs in wetlands where thickets of wetland shrubs (e.g. Melaleuca, Agonis spp.) provide patches of tall cover within sedge-dominated habitat. In the Murray–Darling Basin, Australasian Bitterns occur in floodplain swamps that may include lignum (Duma florulenta) shrubs within sedge or reed beds as well as in commercial rice-fields (NSW Riverina). Despite occurring in a range of wetland types, breeding is only known to occur at a smaller number of locations.

As a guide, habitat critical to the survival of the Australasian Bittern can be considered to include:

• Any natural wetland habitat where the species is known or likely to occur (breeding or foraging habitat) within the indicative distribution map (Figure 1).

Habitat critical to the survival of the Australasian Bittern occurs across a wide range of land tenures, including on Indigenous Protected Areas, freehold land, conservation reserves, and national parks. It is essential that the locations where the species regularly occurs is given the highest protection and conservation measures target these productive habitats. Areas that buffer nesting and foraging habitats should also be considered in management for the species. Buffer zones will depend on the nature and location of the activity (e.g. adjacent to the wetland vs activity in the catchment) and can be informed by expert opinion.

When considering developments in any part of the Australasian Bittern’s range, including in areas where the species ‘may occur’, surveys for occupancy at the appropriate times of the year remain an important tool in establishing the areas importance for the Australasian Bittern. In addition, consistent with natural fluctuations in availability of wetland habitat in Australia (whether an entire wetland or a temporarily inundated zone of a wetland), it is also important to note that the Australasian Bittern opportunistically use areas depending on the occurrence of suitable habitat and prey species so areas that may be important habitat over time might not have birds in any given year. This pattern of habitat use means that recent survey data and historical records and presence of suitable habitat need to be considered when assessing the relative importance of a site or region for the Australasian Bittern.

Chapter 2

Threats

2.1 Historical causes of decline

It is thought that the Australasian Bittern has been in decline for at least the past 30 years and declines since 2000 have been more pronounced (Garnett et al. 2011).

The decline has been detected across both the eastern and western subpopulations and is associated with the loss of key breeding habitats (Garnett et al. 2011; DBCA 2018; Herring et al. 2019a).

2.2 Current threatening processes

The main identified threats to the Australasian Bittern are the reduction in extent and quality of habitat due to the diversion of water away from wetlands (primarily for irrigation as well as groundwater extraction), the drainage of swamps, climate variability and change, the loss or alteration of wetland habitats due to urban and agricultural development, peat mining, predation by introduced animals such as foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and cats (Felis catus), reduced water quality as a result of increasing salinity, siltation and pollution, and overgrazing by livestock and detrimental fire regimes (Jaensch and Vervest 1988; Marchant and Higgins 1990; Kingsford and Thomas 1995; Garnett and Crowley 2000; Kingsford 2000; Jaensch 2004; Pickering 2013; DBCA 2018; Herring et al. 2019a).

2.2.1 Reduced wetland availability due to changed water regimes

The major threat to the Australasian Bittern in Australia is the reduction in extent and quality of habitat, due to the diversion of water away from wetlands (primarily for irrigation as well as groundwater extraction), peat mining and the drainage of swamps (Marchant and Higgins 1990; Kingsford and Thomas 1995; Garnett and Crowley 2000; Kingsford 2000; Jaensch 2004; Garnett et al. 2011; DBCA 2018). Over the past 100 years, many suitable wetland sites in both eastern and south western Australia have been lost because of the alteration of habitat (Kingsford 2000; Garnett et al. 2011). Across the range of the species, proposals to expand or create new irrigation schemes (dams) need to be mindful of the potential impacts to Australasian Bittern and its habitats, particularly during extended drought conditions.

In the Murray–Darling Basin, reduction in floodplain inundation due to water harvesting and alteration of drainage systems has adversely affected much of the Australasian Bittern’s seasonal habitat (Jaensch 2004). Many of the Murray–Darling Basins wetlands are no longer inundated or are rarely available for use by the species due to river regulation and water harvesting for irrigation (Jaensch, pers. comm., 2005). For example, there has been a 70 per cent reduction in large water flows to the Gwydir Wetlands, New South Wales, which are listed as both nationally important and Ramsar wetlands. As a consequence, the Gwydir Wetlands now only floods five per cent of the time compared to a previous 17 per cent of the time (Kingsford 2000). In addition, the Macquarie Marshes Ramsar wetland has reduced in size by 40–50 per cent as a result of a 21 per cent decline in the flow of water to the wetland (Kingsford 2000).

Flow regulation is impacting many rivers in the Murray–Darling Basin, with approximately 4,000 dams, weirs and other barriers (Lintermans 2007) facilitating water collection in impoundments, diversion through irrigation channels and direct pumping from rivers, largely for agricultural use. Across the Basin water regulation hassignificantly altered natural flow regimes, particularly regarding seasonal and inter-annual flows and floodplain inundation (Kingsford et al. 2015). It has also altered both the quality and availability of floodplain habitats, such as backwaters and billabongs, due to reduced flooding. The Murray–Darling Basin Authority has focused environmental water priorities on floodplain inundation to provide lateral connectivity (MDBA 2015). Environmental watering events in the Barmah-Millewa Ramsar site and Lowbidgee wetlands have supported significant numbers of Australasian Bitterns, with confirmed breeding (Belcher et al. 2016, Herring et al. 2019b). Watering events in the Kerang Lakes region, Lachlan, Macquarie and Gwydir catchments have most likely achieved similar breeding events that benefit the species in the Murray–Darling Basin.

Increased extraction of groundwater due to escalating demand for water in urban areas and declining rainfall is another factor in wetland availability, especially on the Swan Coastal Plain, Western Australia (DBCA 2018). Groundwater dependent wetlands in this sandplain can be dry for longer periods. In contrast, as both an immediate and continued gradual consequence of clearing of woodland for agriculture in the wheatbelt of south-western Australia, runoff to many wetland basins has increased, drowning the otherwise seasonally inundated wooded and sedgeland—some of which probably was used intermittently by Australasian Bittern—leaving bare basins with only dead trees remaining (DBCA 2018).

2.2.2 Habitat loss and/or alteration

Loss of wetlands

Over the past 150 years, many wetlands suitable for Australasian Bittern in both eastern and south western Australia have been destroyed, especially due to drainage (Kingsford 2000; Garnett et al. 2011). While occurring throughout the range of occurrence of the Australasian Bittern, this impact would have been especially severe in the formerly extensive swampy landscape of the south-east of South Australia (drained mainly from 1949–1972) and in and near each of the major cities of southern Australia.

Ongoing loss of swampy wetlands suitable for or known to have supported Australasian Bittern, with replacement by urban development and infrastructure, has continued in more recent decades notably in the rapid expansion of the suburbs of Perth, Melbourne and the Gold and Sunshine Coasts, Queensland.

As well as outright loss of wetlands, wetland vegetation has been altered in some parts of the species range. In New South Wales, much of the Gwydir Ramsar wetlands have been cleared and converted from grazing to cropped agriculture, leaving only very small areas of habitat suitable for bitterns (R. Jaensch, pers. comm., 2005). One of the drivers for this trend has been spread of Lippia (Phyla canescens), a mat-forming weed that thrives under conditions of reduced inundation, reducing suitable natural fodder for livestock and forcing landholders to control it by ploughing and cropping. An additional risk for natural wetlands is geomorphic change – natural erosion and sedimentation processes that can isolate wetlands (i.e. Macquarie Marshes Ramsar site, New South Wales). This is primarily a land and water management issue that is exacerbated by river regulation, catchment land use (erosion) and water quality (turbidity).

Because of its comparatively specialised habitat requirements (i.e. densely vegetated wetlands), the species is much more sensitive to habitat loss than many other wetland birds (Garnett and Crowley 2000). Although many sites occupied by Australasian Bitterns are now protected, the species continues to be threatened by ongoing wetland loss and changes to vegetation cover. The encroachment by River Red Gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) and subsequent loss of the open Moira Grass Plains from areas like the Barmah-Millewa Ramsar wetlands has the potential to reduce foraging opportunities for Australasian Bitterns. The coastal zone in Australia is still subject to intense and escalating pressure from housing, semi–rural and other developments and the swampy vegetation in some wetlands has declined as wetlands become deeper sumps for increased stormwater from paved and other hard surfaces in expanding urban areas (Jaensch 2004).

Fire

Intense and frequent bushfires or prescribed burning in wetlands reduces the density and cover of vegetation that forms the core habitat of the Australasian Bittern. Wetlands in southwest Australia have lost vegetation habitat due to summer fires when wetlands are dry (DBCA 2018). Many wetlands that support Australasian Bittern have deep peat beds. Severe fires can burn these peat beds and convert wetlands from shallow wetlands suitable for Australasian Bittern to deep wetlands with only minimal fringing vegetation which do not support Australasian Bittern. The combination of a period of dry phases followed by fire resulted in the loss of an estimated 60–70 per cent of the reed beds in the Macquarie Marshes Ramsar site, New South Wales (Oct-Nov 2019). While the Marshes would not have been providing habitat for Australasian Bitterns at the time, given that the wetlands were dry, this fire event is likely to have detrimental effect on the rigour and extent of the reed beds in this system.

Individual wetlands may require different fire regimes depending on vegetation type and location. In Western Australia, without occasional fire, rush or sedge dominated wetlands may become too dense for the movement of Australasian Bittern (A. Clarke, pers. comm. cited in DBCA 2018). In Victoria, the Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Area are working closely with Traditional Owners and other landholders to conduct traditional burning across wetland areas of the Tyrendarra Indigenous Protected Area. Wetland areas are being burnt using traditional patch burning techniques to enhance habitat for the Australasian Bittern, encourage the regeneration of native plant species and support cultural practices.

Livestock overgrazing

The Australasian Bittern is sensitive to habitat damage as it has relatively specialised habitat requirements, preferring wetlands with dense vegetation. Livestock can trample nests, and through grazing damage the available foraging and shelter habitat, reducing access to food and exposing Australasian Bitterns to predators.

2.2.3 Climate variability and change

In Western Australia the majority of the range of the Australasian Bittern is within an area which has experienced reduced rainfall over the past few decades. The Western Australian Australasian Bittern Recovery Plan identifies climate change (i.e. changes in precipitation and evaporation rates) as one of the primary threatening process to Australasian Bittern populations (Pickering 2013, DBCA 2018). A drying climate reduces the peak water level and peak area of wetting in wetlands, which effectively reduces the quality and quantity of breeding wetlands and drought refuges available. Seasonal wetlands are also experiencing reduced inundation periods, increasing the risk of wildfire at these sites.

In the Murray–Darling Basin a major concern is an increased frequency and intensity of droughts which is likely to exacerbate the already extreme fluctuations in wetland habitat availability combined with seasonal shifts in rainfall. In dry periods there is also less water available for rice farming, which supports around 59 per cent of the national population, and greater pressure on rice farmers to use water-saving agronomy or switch to alternative crops like cotton (Herring et al. 2019a).

2.2.4 Reduced water quality

Reduced water quality due to increased salinity, acidification, siltation and pollution is having an ongoing impact on the species’ habitat. In the wheatbelt of inland south western Australia, historical clearing of extensive natural woodlands for crops and sheep farming has led to rising water tables which has increased salt levels on and near the land surface, including in wetlands and waterways. Salinisation of wetlands can alter the vegetation and faunal characteristics at a site, resulting in wetlands that no longer meet the ecological requirements of Australasian Bittern. Salinisation has impacted hundreds of inland and south-eastern coastal swamps and has excluded the Australasian Bittern from former inland locations (Jaensch 2004). For example, Yarnup Swamp in the Muir–Unicup wetlands has not been used by the Australasian Bittern since the mid-1980s because of its high salinity. Since Cobertup East Swamp in the Muir-Unicup wetlands became acidified in 2005, Australasian Bittern has no longer been recorded at this swamp (Pickering 2013).

Siltation in waterways occurs due to reduced vegetation cover in catchments resulting from human landuse. At the mouth of the Snowy River, Victoria, siltation has caused the back flow of saline water which has destroyed the species’ reed-bed habitat in Lake Corringle in Victoria. Consequently, the Australasian Bittern is no longer found at this location (Birds Australia 2009).

In the Murray–Darling Basin salinity is a major problem causing extensive degradation in some areas (Kingsford 2000). Elevated salinity could also negatively affect Australasian Bittern prey sources, such as invertebrates.

The regulation of river flows has the potential to reduce water quality by excessively raising or lowering water temperatures, reducing dissolved oxygen levels and increasing nutrient and contaminant loads (Kingsford 2000). These changes can result from altered flows caused by water diversion, impoundment or sustained dry periods reducing run-off. Water quality can also be impacted by urban and agricultural run-off, which can lead to phytoplankton blooms, reduced oxygen levels and increased salinity.

Pollution in wetlands is likely to cause a decline in many of the prey species of the Australasian Bittern, such as eels, freshwater crayfish and frogs which in turn may have a negative effect on bittern populations and their health (Marchant and Higgins 1990).

2.2.5 Invasive species

Invasive herbivores

Invasive herbivores such as pigs, horses, goats and deer degrade wetlands important for Australian Bittern by digging up wetlands edges and removing vegetation cover. Hard hooved species trample wetland vegetation and have to potential to damage nests (DBCA 2018).

Predation

The Australasian Bittern is subject to the predation of eggs and juveniles by foxes (Vulpes vulpes), cats (Felis catus), rats and pigs (Garnett and Crowley 2000; DBCA 2018). Foxes are known to be predators of ground-nesting birds across the range of the Australasian Bittern (NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service 2001), so could be a potential threat

2.2.6 Loss of genetic diversity

The estimated number of mature individuals is 1,300 in Australia (Herring et al. 2019a). In Western Australia, the population is estimated to be between 50–100 individuals (DBCA 2018)). A small population is more susceptible to demographic and genetic stochastic events, which can impact the long term survival of the population. Research is required to understand the genetic structure of Australasian Bittern and may be used to identify important populations and appropriate management units.

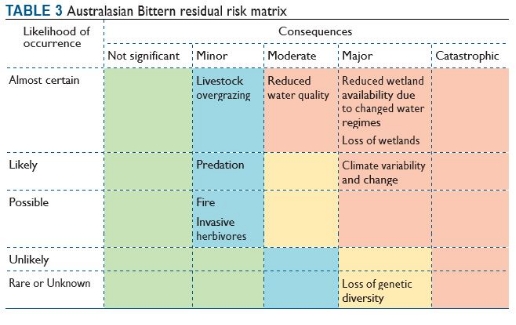

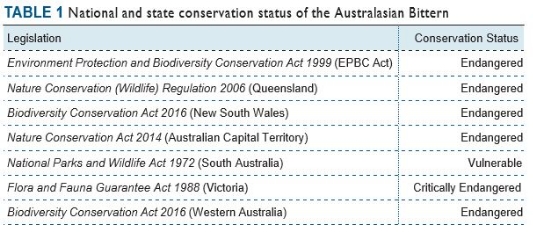

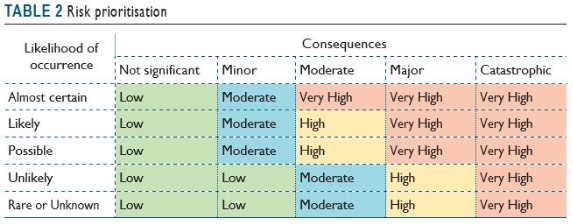

2.2.7 Threat prioritisation

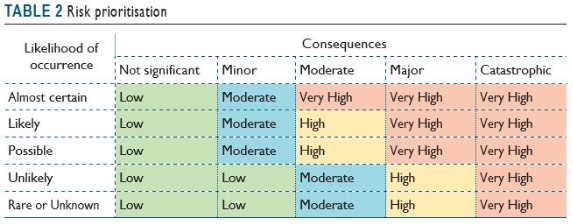

Each of the threats outlined above has been assessed to determine the risk posed to the Australasian Bittern population (Table 3) using a risk matrix (Table 2). This in turn determines the priority for actions outlined below. The threats were considered in the context of the current management regimes. The impact of that threat has been assessed assuming that existing management measures continue to be applied appropriately. If management regimes change then the level of risk associated with threats may also change. The risk matrix considers the likelihood of an incident occurring and the consequences of that incident. Threats may act differently in different parts of the species range and at different times of year, but the precautionary principle dictates that the threat category is determined by the population at highest risk. Population-wide threats are generally considered to present a higher risk.

The risk matrix uses a qualitative assessment drawing on peer reviewed literature and expert opinion. In some cases the consequences of activities are unknown. In these cases, the precautionary principle has been applied. Levels of risk and the associated priority for action are defined as follows:

• Very High – immediate mitigation action required

• High – mitigation action and an adaptive management plan required, the precautionary principle should be applied

• Moderate – obtain additional information and develop mitigation action if required

• Low – monitor the threat occurrence and reassess threat level if likelihood or consequences change

Categories for likelihood are defined as follows:

• Almost certain – expected to occur every year

• Likely – expected to occur at least once every five years

• Possible – might occur at some time

• Unlikely – such events are known to have occurred on a worldwide basis but only a few times

• Rare or Unknown – may occur only in exceptional circumstances; OR it is currently unknown how often the incident will occur

Categories for consequences are defined as follows:

• Not significant – no long-term effect on individuals or populations

• Minor – individuals are adversely affected but no effect at population level

• Moderate – population recovery stalls or reduces

• Major – population decreases

• Catastrophic – population extinction

Chapter 3

Populations under particular pressure

The actions described in this Recovery Plan are designed to provide ongoing protection for Australasian Bitterns throughout their Australian range. The meta-population structure of the species is largely unknown. Australasian Bitterns persist as at least two isolated, subpopulations in eastern and south western Australia. In recent decades, numbers in the previous strong-holds in the Murray–Darling Basin have declined, perhaps permanently due to pressure on water resources and thus now only rare inundation of floodplains. The Western Australian subpopulation has become more restricted with few records away from the south and south-east coasts and Lake Muir wetlands, which is part of the Muir-Byenup System Ramsar wetland (Pickering 2013). There have been few confirmed records from the Swan Coastal Plain since 1992 and surveys in 2007 and 2008 found that half the wetlands that supported the species in 1980 now retained no suitable habitat (Pickering and Gole 2008; Pickering 2013; DBCA 2018). Breeding in South Australia is confirmed from the Bool Lagoon, and the coast from Adelaide to Victorian border. There are few recent Queensland records (Barrett et al. 2003).

All subpopulations covered by this plan have restricted distributions and small population sizes, which present significant challenges for their recovery and exert strong pressures on their survival in the wild. Given these challenges, all subpopulations of Australasian Bittern covered by this plan require strong protective measures.

In Western Australia, the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions have approved a state recovery plan for Australasian Bittern (DBCA 2018). The population is estimated to be between 50–100 individuals. Actions relating to the Western Australian subpopulation should consider both the national and state recovery plans in parallel when implementing research and management actions.

Chapter 4

Recovery plan vision, objectives and strategies

Long-term vision

The Australasian Bittern population has increased in size to such an extent that the species no longer qualifies for listing as threatened under any of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 listing criteria.

Recovery plan objective

The objective of this recovery plan is to demonstrate, by 2032, an increasing trend (compared to 2020 baseline counts) in the number of mature individuals being recorded in annual surveys at key locations, and to ensure that habitat critical to the survival of the Australasian Bittern is protected and managed to meet the ecological requirements of the species.

Strategies to achieve objectives

1 Implement management actions that mitigate or reduce threats to Australasian Bittern and their habitat

2 Enhance the quality, extent and protection of suitable habitat for the Australasian Bittern

3 Undertake research and monitoring to improve knowledge of the biology, ecology and population trends of Australasian Bittern

4 Increase stakeholder participation in Australasian Bittern conservation and management

5 Coordinate, review and report on recovery progress

Chapter 5

Actions to achieve the specific objectives

Actions identified for the recovery of Australasian Bittern are described below. It should be noted that some of the objectives are long-term and may not be achieved prior to the scheduled five-year review of the Recovery Plan. Priorities assigned to actions should be interpreted as follows:

Priority 1: Taking prompt action is necessary in order to mitigate the key threats to Australasian Bittern and also provide valuable information to help identify long-term population trends.

Priority 2: Action would provide a more informed basis for the long-term management and recovery of Australasian Bittern.

Priority 3: Action is desirable, but not critical to the recovery of Australasian Bittern or assessment of trends in that recovery.

Chapter 6

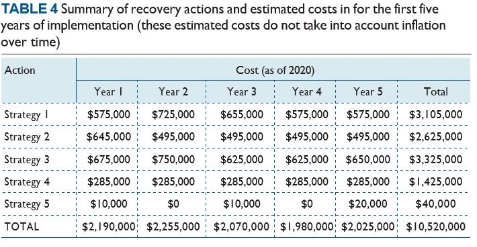

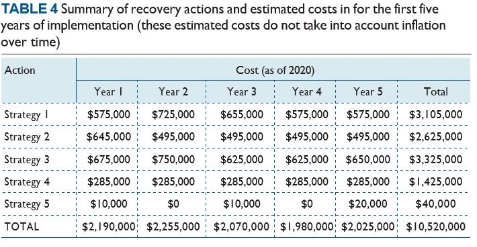

Duration and cost of the recovery process

It is anticipated that the recovery process will not be achieved prior to the scheduled five-year review of the Recovery Plan. The cost of implementation of this plan should be incorporated into the core business expenditure of the affected organisations, and through additional funds obtained for the explicit purpose of implementing this

Recovery Plan. It is expected that Commonwealth and state agencies will use this plan to prioritise actions to protect the species and enhance its recovery, and that projects will be undertaken according to agency priorities and available resources. All actions are considered important steps towards ensuring the long-term survival of the species. The indicative cost of recovery plans actions was derived from expert elicitation and public comments received in 2020.

Chapter 7

Effects on other native species and biodiversity benefits

The Recovery Plan focuses on the management, protection, restoration and creation of freshwater and coastal wetlands, the principal breeding habitat for Australasian Bittern. Australia has a diverse waterbird fauna adapted to these wetlands, many of which are unpredictable in their availability and habitats (Kingsford and Norman 2002). Many waterbird species exploit the high productivity of those wetlands that dry out after being inundated temporarily (Taylor 2003). Consequently, appropriate management of these wetlands will benefit many plant and animal species, as well as associated ecological communities.

The wide distribution and unpredictable nature of freshwater and coastal wetlands makes it difficult to identify population trends of species within them.

Other threatened species occur in these habitats, such as the Australian Painted Snipe (Rostratula australis), which can have conflicting habitat requirements for targeted management (Herring and Silcocks, 2014; Herring et al. 2019a). The Australasian Bittern, an unusually attractive and enigmatic resident waterbird, may be of value as a flagship species to highlight the importance of conserving these habitats.

Chapter 8

Social and economic considerations

Wetlands are a vital element of national and global ecosystems and economies. At the most fundamental level, wetlands are a key part of the water cycle, playing critical roles in maintaining the general health of Australia’s rivers, estuaries and coastal waters. Wetlands protect our shoreline from wave action, mitigate the impacts of floods, absorb pollutants and provide habitats for animals and plants, including several species that are threatened. Wetlands are also critical to maintaining and improving our quality of life. They provide tangible benefits to the Australian economy, such as employment opportunities. Wetlands purify our water and are a focal point for recreational activities. They form nurseries for fish and other freshwater and marine life and, as such are of critical importance to Australia’s commercial and recreational fishing industries. In some areas, wetlands support grazing, forestry and cropping activities.

As habitats critical to the survival of the species are broadly identified, there is potential for developments to be restricted under the EPBC Act development assessment and approval process. This may include increased costs due to the assessment processes, requirements to provide offset funding to secure or rehabilitate habitat, or for other threat mitigation work.

Limits on further development of wetland habitat may impact on some landowners, other land managers and developers. These restrictions may not significantly impact on agricultural or irrigation industries since many of the suitable areas have already been developed and the remaining critical habitats are generally located in protected conservation areas and remote locations. These areas are, therefore, relatively less attractive for further development.

A large network of community volunteers across Australia actively participate in BirdLife Australia’s coordinated annual surveys for migratory shorebirds and wetland birds. Involvement can provide social benefits with community members and engaged groups having a sense of achievement, inclusion, community spirit and pride whilst gaining enjoyment and appreciation of their surrounding natural environment. The community education components of the program also promote community ownership, provide community support and encourage active involvement in protecting local natural resources. Additional social benefits include encouraging passive recreation, appreciation of natural aesthetic values and increased awareness and appreciation of Indigenous cultural values.

Chapter 9

Affected interests

Organisations and individuals likely to be affected by the actions proposed in this plan include: government agencies (Commonwealth, state and territory, local), particularly those involved with wetland environments and conservation programs; private landholders; Indigenous land and sea management groups (including ranger programmes); researchers; bird watching groups; conservation groups; wildlife interest groups; 4WD and fishing groups; environmental consulting companies; tourism operators; industry and commercial bodies; and, proponents of agricultural development in the vicinity of important habitat. However, this list should not be considered exhaustive, as there may be other interest groups that may like to be included in the future or need to be considered when specialised tasks are required.

The following table lists some of the interest groups, how they could contribute to the success of the plan and the potential benefits/impacts that may emerge from the Plan’s implementation:

Affected interests

Chapter 10

Consultation

The National Recovery Plan for the Australasian Bittern has been developed through extensive consultation with a broad range of stakeholders. The consultation process brought together key species experts and conservation managers, from a range of different organizations, to categorize ongoing threats to the Australasian Bittern, and identify knowledge gaps and potential management options. Consultation included representatives from government agencies, non-government organisations, researchers and local community groups. During the drafting process the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (Cwlth) continued to work closely with key stakeholders.

Notice of the draft plan was made available for public comment for a minimum of three months between 20 December 2019 and 17 April 2020. Any comments received that were relevant to the survival of the species were considered by the Threatened Species Scientific Committee as part of its assessment process.

Chapter 11

Organisations/persons involved in evaluating the performance of the plan

This plan should be reviewed no later than five years from when it was endorsed and made publicly available. The review will determine the performance of the plan and assess:

• whether the plan continues unchanged, is varied to remove completed actions, or varied to include new conservation priorities; or

• whether a recovery plan is no longer necessary for the species as either conservation advice will suffice, or the species are removed from the threatened species list.

As part of this review, the listing status of the species will be assessed against the EPBC Act species listing criteria.

The review will be coordinated by the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water in association with relevant Australian and state government agencies and key stakeholder groups such as non-governmental organisations, local community groups and scientific research organisations.

Key stakeholders who may be involved in the review of the performance of the National Recovery Plan for the Australasian Bittern, include organisations likely to be affected by the actions proposed in this plan and are expected to include:

Australian Government

• Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

State/territory governments

• Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate (ACT)

• Department of Planning and Environment (NSW)

• Department of Environment and Science (Qld)

• Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (Vic)

• Department of Environment and Water (SA)

• Department of Natural Resources and Environment (Tas)

• Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (WA)

• Natural resource management bodies in coastal regions

• Local government in coastal regions

Non-government organisations

• BirdLife Australia

• Local conservation groups

• Local communities

• Private landholders

• Indigenous communities

• Universities and other research organisations

• Industry

• Recreational sports and associations

• Recreational fishers and associations

• Recreational boaters

Chapter 12

References

Barrett, G., Silcocks, A., Barry, S., Cunningham, R. and Poulter, R. (2003) The New Atlas of Australian Birds. Melbourne, Victoria: Birds Australia.

Belcher, C., Borrell, A., Davidson, I. and Webster, R. (2017) Australasian Bittern Surveys in the Murray Valley and Barmah National Parks 2016–2017. Unpublished Report by New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service, Sydney.

BirdLife International (2019) Botaurus stellaris. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22697346A86438000. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22697346A86438000.en. Downloaded on 13 September 2019.

Birds Australia (2009). Important Bird Areas online database. Available on the Internet at: http://www.birdata.com.au/ibas

Birds Australia (2009). Personal communication by letter, 26 March 2009. Carlton, Victoria.

Birds Australia (2010). Australasian Bittern Botaurus poiciloptilus National Population Estimates for Spring – Summer 2009–10. In possession of Birds Australia, Carlton.

Bitterns in Rice Project (2016). The Story So Far: 2012-2016. www.bitternsinrice.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Bitterns-in-Rice- Project-2012-2016-summary-booklet.pdf Accessed 13 September 2019.

Bitterns in Rice Project (2019). Tracking Bunyip Birds. www.bitternsinrice.com.au/ tracking-bunyip-birds/ Accessed 13 September 2019.

Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (2018). Australasian Bittern (Botaurus poiciloptilus) Western Australian Recovery Plan. (Compiled by Anderson, G., Blyth, J., Burbidge, A.H., Clarke, A., Comer, S., Gole, C., Hearne, R., Lane, J., Page, M., Pickering, R., and Williams, K.). Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions. Wildlife Management Program No. # 64, Perth, W.A. Available at: https://www.dpaw.wa.gov.au/images/documents/plants-animals/threatened-species/recovery_plans/WA%20Recovery%20Plan_Aust%20Bittern_FINAL_2018.pdf

Garnett, S. and Crowley, G. (2000) The Action Plan for Australian Birds. Environment Australia. Canberra.

Garnett, S.T., Szabo, J.K. and Dutson, G. (2011) The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2010. CSIRO Publishing. Melbourne.

Heather, B., Robertson, H. (2000) The Field Guide to the Birds of New Zealand, revised ed. Viking, Auckland.

Herring, M.W., Barratt P., Burbidge, A.H., Carey, M., Clarke, A., Comer, S., Green, B., Pickering, R., Purnell, C., Silcocks, A., Stokes, V., Znidersic, E., Jaensch, R. P., Garnett ST (2021) Australasian Bittern Botaurus poiciloptilus. In Action Plan for Australian Birds 2020. (Eds S.T. Garnett and G.B. Baker) CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne.

Herring, M. W. and Silcocks, A (2014) The use of rice fields by the endangered Australian Painted Snipe (Rostratula australis): a rare opportunity to combine food production and conservation? Stilt 66: 20-29.

Herring, M., Veltheim, I. & Silcocks, A. (2016) Robbie’s gone a roaming. Australian Birdlife 5 (3): 26-31.

Herring, M.W., Robinson, W., Zander, K.K. and Garnett, S.T. (2019a) Rice fields support the global stronghold for an endangered waterbird. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 284: 106599.

Herring, M.W. (2019b) Bittern Surveys in the Lowbidgee Wetlands: December 2018 – January 2019 Summary report. Unpublished report by Murray Wildlife to New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage.

Jaensch R (2004). Australasian Bittern. Wingspan 14: 4.

Jaensch R (2005). Personal Communication, June 2005 Wetlands International – Oceania.

Jaensch RP and Vervest RM (1988). Ducks, Swans and Coots in south–western Australia: the 1986 and 1987 counts. RAOU Report Series 31: 1–32.

Jaensch RP, Vervest RM and Hewish MJ (1988). Waterbirds in nature reserves of south–western Australia 1981–1985: reserve accounts. RAOU Report Series 30.

Kingsford RT (2000). Ecological impacts of dams, water diversions and river managements on floodplains wetlands in Australia. Austral Ecology 25: 109–127.

Kingsford, R.T., Mac Nally, R., King, A., Walker, K.F., Bino, G., Thompson, R., Wassens, S., & Humphries, P. (2015). A commentary on ‘Long-term ecological trends of flow-dependent ecosystems in a major regulated river basin’ by Matthew J. Colloff, Peter Caley, Neil Saintilan, Carmel A. Pollino and Neville D. Crossman. Marine and Freshwater Research 66, 970–980.

Kingsford, R.T. and Norman, F.I. (2002) Australian Waterbirds – products of the continent’s ecology. Emu 102: 47-69.

Kingsford RT and Thomas RF (1995). The Macquarie Marshes in arid Australia and

their waterbirds: a five year history of decline. Environmental Management 19: 867–878.

Lintermans, M. (2007). Fishes of the Murray–Darling Basin: An introductory guide. Murray–Darling Basin Commission Publication No. 10/07.

Marchant, S. and Higgins, P.J. (eds) (1990) Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Volume One – Ratites to Ducks. Oxford University Press. Melbourne.

Martínez-Vilalta, A., Motis, A., Kirwan, G.M., (2019). Australasian Bittern (Botaurus poiciloptilus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A., de Juana, E. (Eds.), Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. retrieved from on 20 April 2020.

Murray–Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) (2015). 2015–16 Basin Annual Environmental Watering Priorities. Licensed from the Murray–Darling Basin Authority under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence, Murray–Darling Basin Authority, Canberra.

NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (2001). Threat Abatement Plan for Predation by the Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes). NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. Hurstville.

Pickering, R. (2013) Australasian Bittern in Southwest Australia. Perth, WA: BirdLife Australia. Available at http://birdlife.org.au/projects/bittern-project.

Pickering, R. and Gole, C. (2008) Swan coastal plain Australasian Bittern surveys 2007-2008. Unpublished report.

Pizzey, G. and Knight, F. (1997) The Graham Pizzey and Frank Knight Field Guide to the Birds of Australia. Angus and Robertson. Sydney.

Serventy, D.L. and Whittell, H.M. (1976) Birds of Western Australia. University of Western Australia Press. Perth.

Taylor, I.R. (2003) Australia’s temporary wetlands: what determines their suitability as feeding and breeding sites for waders? Wader Study Group Bulletin 100: 54-58.

TSSC (Threatened Species Scientific Committee) (2011) Commonwealth Listing Advice on Botaurus poiciloptilus (Australasian Bittern). Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Canberra, ACT: Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Available on the internet at: http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/species/ pubs/1001-listing-advice.pdf