Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (Threat Abatement Plan for Predation by Feral Cats 2024) Instrument 2024

I, Tanya Plibersek, the Minister for the Environment and Water, make the Threat abatement plan for predation by feral cats 2024 in the following instrument, jointly with the Northern Territory, South Australia, Tasmania, New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory, Western Australia and Victoria.

Dated 18.12.24

Tanya Plibersek

Minister for the Environment and Water

1 Name

This instrument is the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (Threat Abatement Plan for Predation by Feral Cats 2024) Instrument 2024.

2 Commencement

This instrument commences on the day after it is registered.

3 Authority

This instrument is made under subsection 270B(3) of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

4 Jointly made threat abatement plan

The Threat abatement plan for predation by feral cats 2024 in this instrument is jointly made with the Northern Territory, South Australia, Tasmania, New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory, Western Australia and Victoria, as agreed by:

(a) the following State and Territory Ministers:

(i) the Minister for Lands, Planning and Environment (Northern Territory);

(ii) the Minister for Climate, Environment and Water (South Australia);

(iii) the Minister for the Environment (Tasmania);

(iv) the Minister for the Environment (New South Wales);

(v) the Minister for Climate Change, Environment and Water (Australian Capital Territory);

(vi) the Minister for Environment (Western Australia); and

(vii) the Minister for Environment (Victoria).

Threat abatement plan for predation by feral cats 2024

© Commonwealth of Australia 2024

Ownership of intellectual property rights

Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights) in this publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia (referred to as the Commonwealth).

Creative Commons licence

All material in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence except content supplied by third parties, logos and the Commonwealth Coat of Arms.

Inquiries about the licence and any use of this document should be emailed to copyright@dcceew.gov.au.

Cataloguing data

This publication (and any material sourced from it) should be attributed as: DCCEEW 2024, Threat abatement plan for predation by feral cats 2024, Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, Canberra. CC BY 4.0. It should be considered in conjunction with: DCCEEW 2024, Background document for the threat abatement plan for predation by feral cats 2024, Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, Canberra. CC BY 4.0.

This publication is available at: dcceew.gov.au/environment/biodiversity/threatened/publications/tap/threat-abatement-plan-feral-cats.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

GPO Box 3090 Canberra ACT 2601

Telephone 1800 920 528

Web dcceew.gov.au

Disclaimer

The Australian Government acting through the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water has exercised due care and skill in preparing and compiling the information and data in this publication. Notwithstanding, the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, its employees and advisers disclaim all liability, including liability for negligence and for any loss, damage, injury, expense or cost incurred by any person as a result of accessing, using or relying on any of the information or data in this publication to the maximum extent permitted by law.

Acknowledgements

The department thanks the stakeholders who contributed their input to the development of this plan, and Professor Sarah Legge and Professor John Woinarski for their support in preparing this plan.

Acknowledgement of Country

Our department recognises the First Peoples of this nation and their ongoing connection to culture and country. We acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples as the Traditional Owners, Custodians and Lore Keepers of the world's oldest living culture and pay respects to their Elders past, and present.

Front cover: Feral cat © Copyright Joanne Heathcote

This threat abatement plan is jointly made by the following governments.

Contents

1 Summary...............................................................1

2 Introduction.............................................................5

2.1 Threat abatement plans................................................5

2.2 Review of the 2015 threat abatement plan..................................6

2.3 This threat abatement plan..............................................6

2.4 Consultation to inform development of this threat abatement plan................8

3 Cat definitions, ecology, distribution and abundance...............................9

3.1 Cat definitions.......................................................9

3.2 Cat ecology........................................................11

3.3 Cat distribution and abundance..........................................12

4 Cat impacts.............................................................13

4.1 Predation..........................................................13

4.1.1 Which extant native species are most susceptible to cat predation?..........13

4.1.2 Which ecological communities are most susceptible to cat impacts?.........15

4.1.3 Factors that amplify cat predation impacts............................16

4.2 Competition........................................................16

4.3 Disease ...........................................................17

4.4 Public amenity......................................................18

4.5 First Nations cultural values............................................18

4.6 Critical habitat, World Heritage properties and National Heritage places............19

5 Cat management........................................................21

5.1 Public support for cat management.......................................23

6 Guiding principles for plan development and implementation.......................24

7 Long term goal..........................................................28

8 Objectives, performance criteria, and actions...................................29

8.1 Objective 1. Coordinate and enhance the legislative, regulatory and planning frameworks. 33

Rationale..........................................................33

Performance Criteria.................................................35

Actions ...........................................................36

8.2 Objective 2. Plan and implement cat management programs within an evidence-based framework, and use this to help maintain broad stakeholder and community support. 38

Rationale..........................................................38

Performance Criteria.................................................39

Actions ...........................................................40

8.3 Objective 3. Undertake research on cat ecology and impacts to inform management undertaken across multiple objectives 46

Rationale..........................................................46

Performance Criteria.................................................47

Actions ...........................................................47

8.4 Objective 4. Refine existing tools and their use, and develop new tools, for directly controlling feral cats 49

Rationale..........................................................49

Performance Criteria.................................................54

Actions ...........................................................54

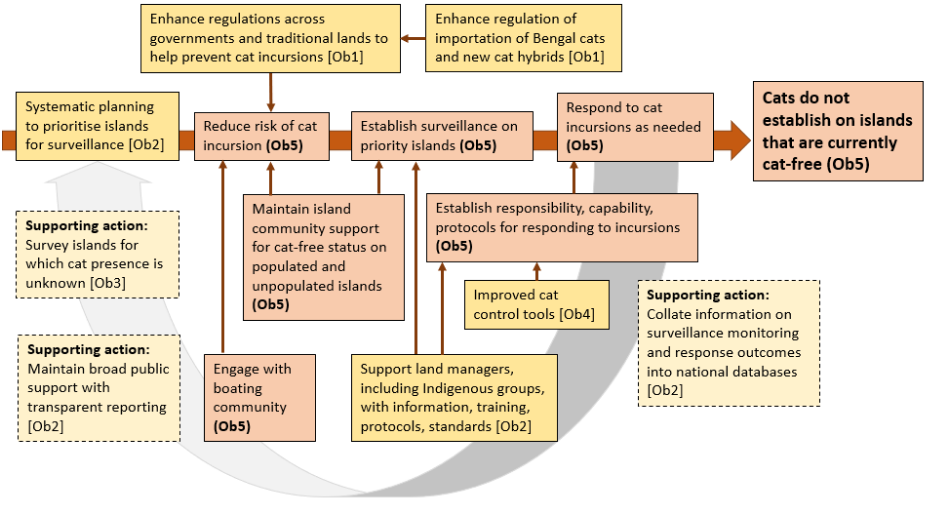

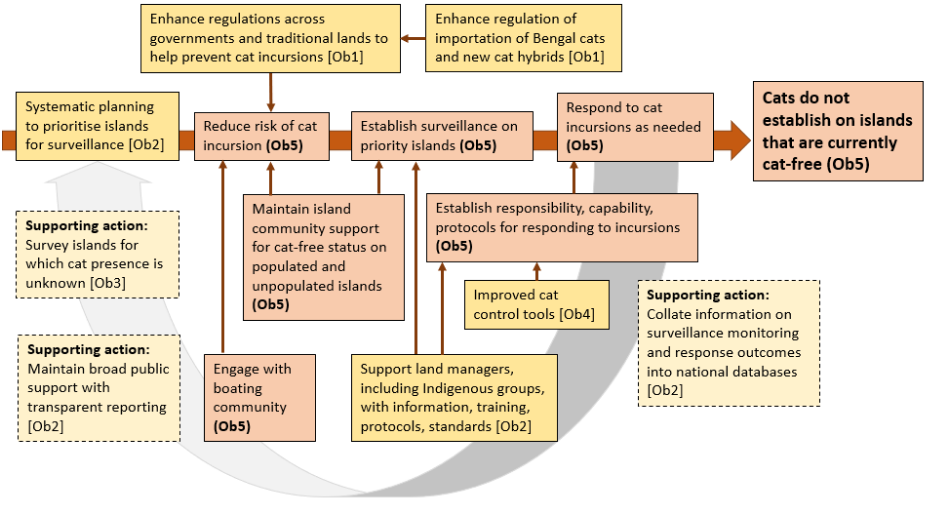

8.5 Objective 5. Prevent cats from spreading further, to islands that are currently without cats 57

Rationale..........................................................57

Performance Criteria.................................................59

Actions ...........................................................60

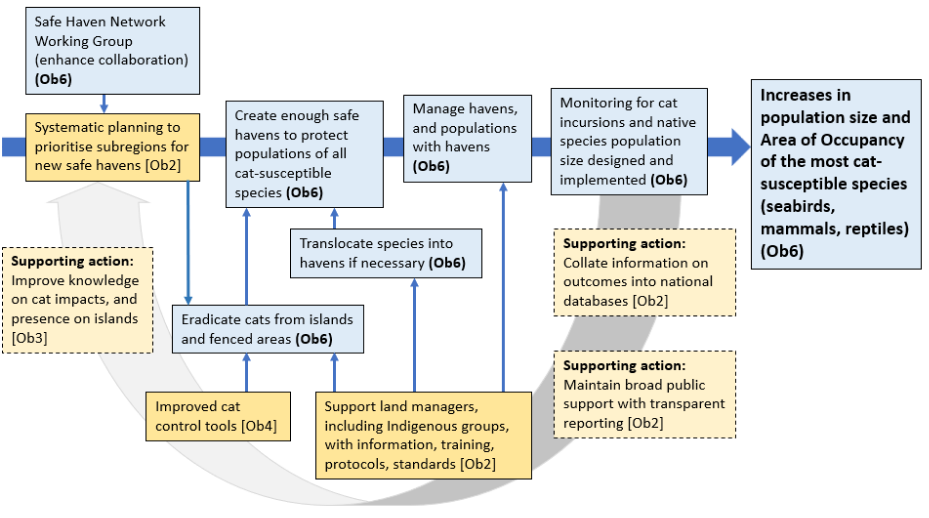

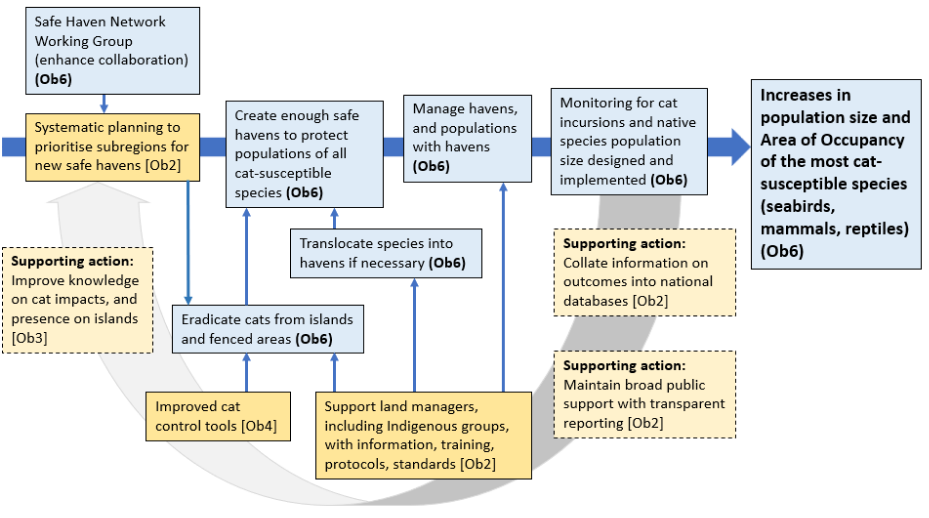

8.6 Objective 6. Protect the most cat-susceptible species: Remove and exclude cats from an expanded network of cat-free islands and fenced havens, and manage those havens to maintain or enhance their conservation values 62

Rationale..........................................................62

Performance Criteria.................................................67

Actions ...........................................................68

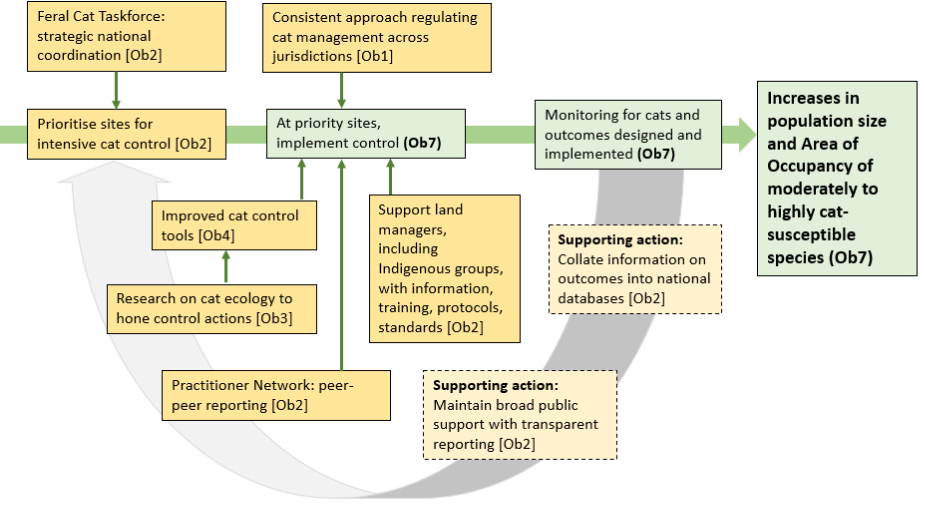

8.7 Objective 7. Protect species with moderate to high susceptibility to cats: Suppress feral cat density in and near prioritised populations of these species 70

Rationale..........................................................70

Performance Criteria.................................................72

Actions ...........................................................73

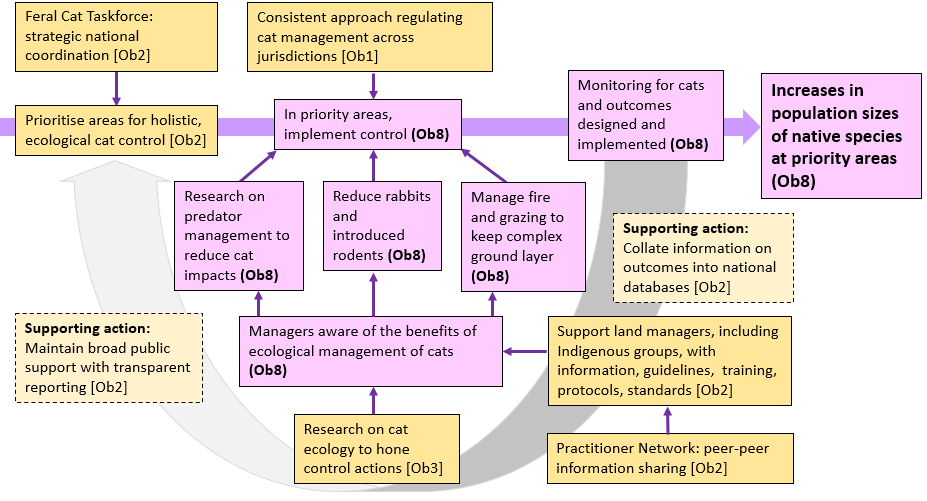

8.8 Objective 8. Reduce the burden of cat predation across all native species using integrated management of habitat and species interactions over large areas 74

Rationale..........................................................74

Performance Criteria.................................................78

Actions ...........................................................79

8.9 Objective 9. Reduce density of free-roaming cats around areas of human habitation and infrastructure 82

Rationale..........................................................82

Performance Criteria.................................................85

Actions ...........................................................86

9 Duration, cost, implementation, and evaluation of the plan.........................90

9.1 Duration..........................................................90

9.2 Implementing and investing in the plan....................................90

9.3 Evaluating implementation of the plan....................................92

10 Planning links...........................................................93

11 Guidance for regulators...................................................95

12 Continuity and adaptation.................................................98

13 Appendices.............................................................99

Appendix 1. Nationally threatened and migratory animal species known to be preyed upon by cats, or for which predation by cats is considered a possible or confirmed threat 99

Appendix 2. Cat-susceptibility of terrestrial mammals, reptiles, and birds................99

Appendix 3. A compilation of the research-focused actions under the strategic themes.....100

Appendix 4. Relevant legislation relating to feral and pet cats, and plans and protocols, in Australian states and territories 104

Appendix 4a. Relevant legislation relating to cats in Australian states and territories..104

Appendix 4b. Other management plans and protocols that focus on, or partly on, feral cats, in Australian states and territories 105

Appendix 5. Feral cat control options in each jurisdiction...........................106

Appendix 6. Indicative relationship of actions in this plan with those in the preceding threat abatement plan 108

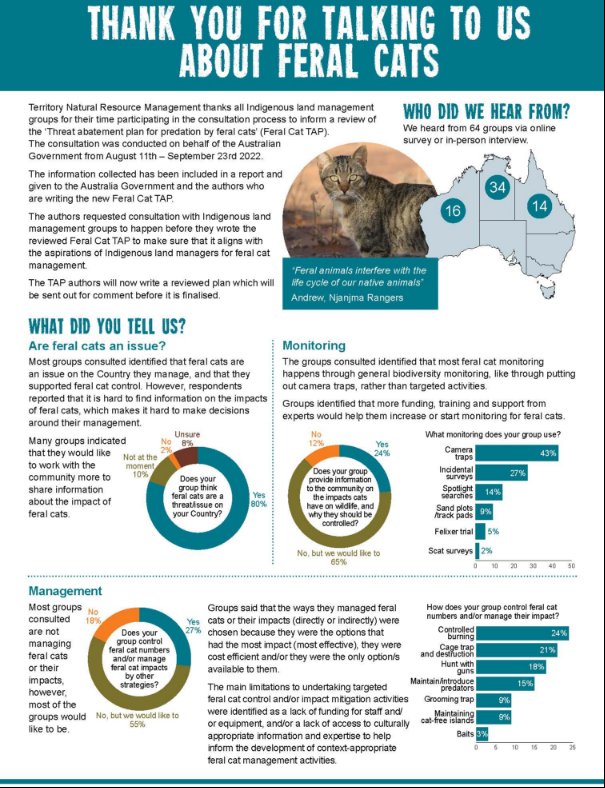

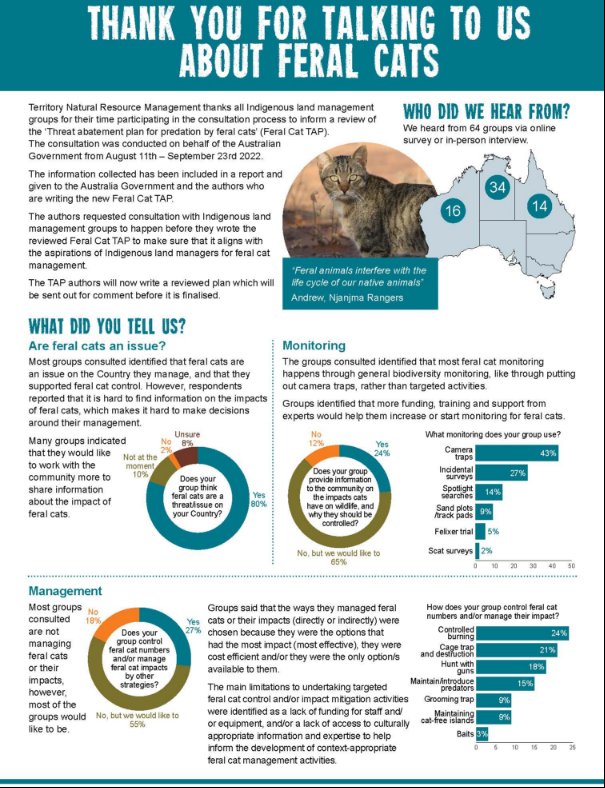

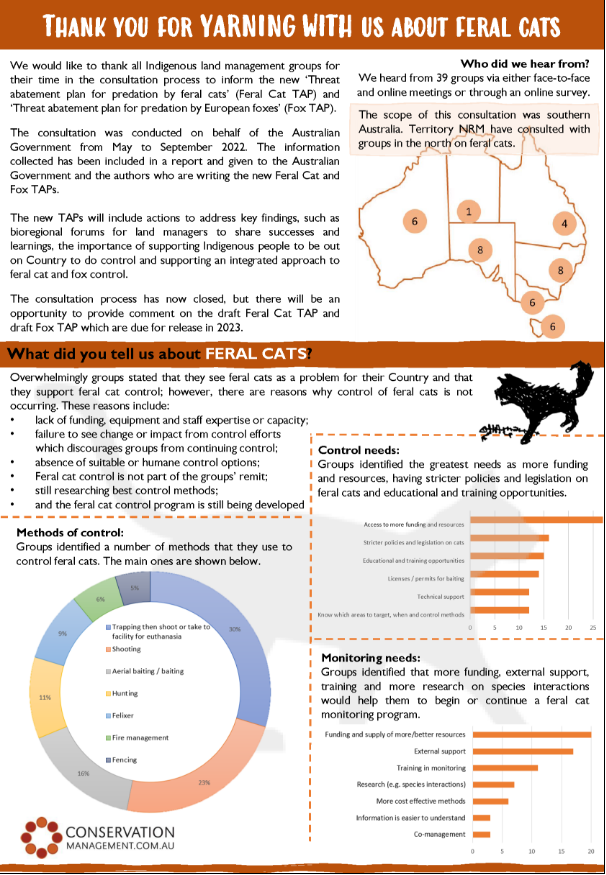

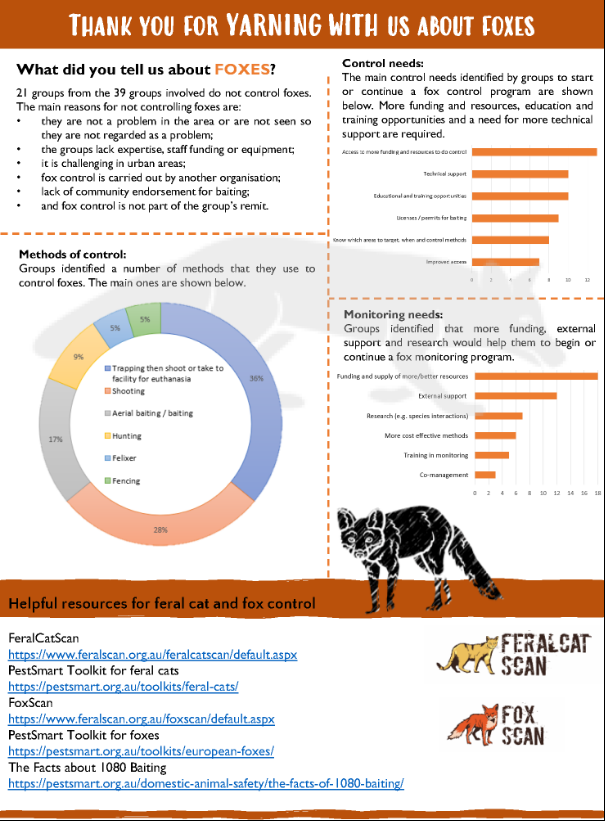

Appendix 7. Summary of early engagement with First Nations groups.................113

14 Glossary..............................................................116

15 List of acronyms........................................................118

16 References............................................................119

Figures

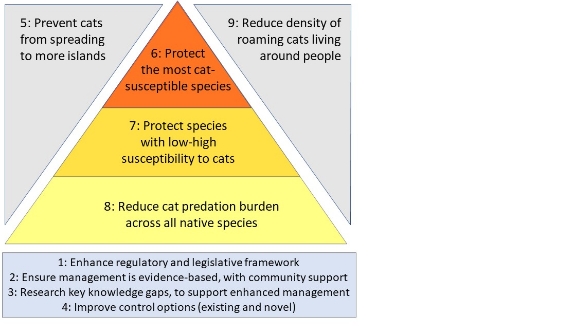

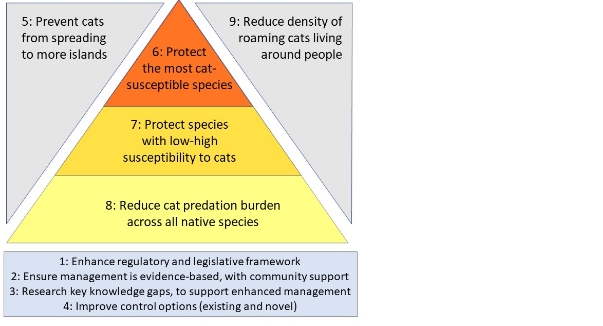

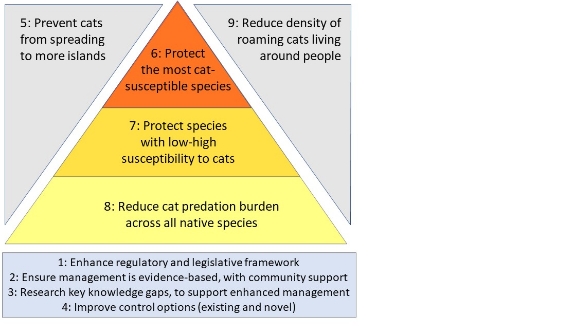

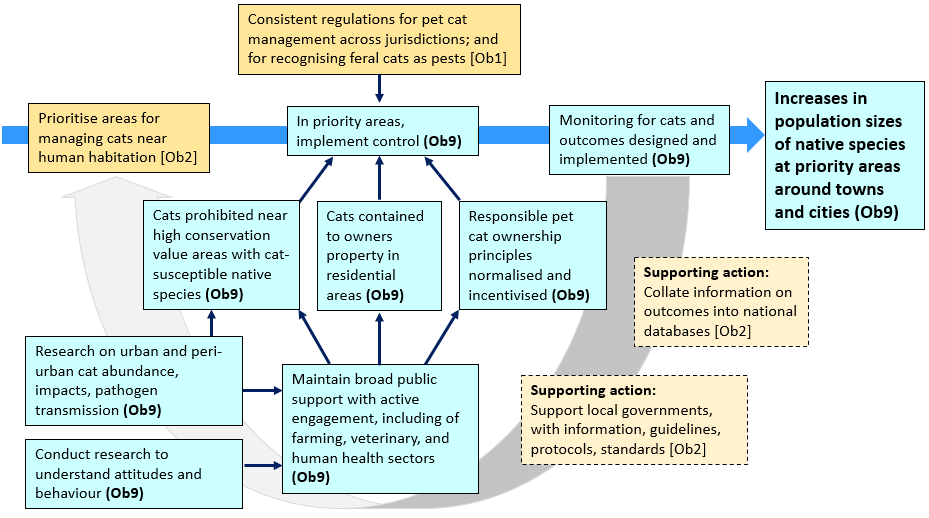

Figure 1 The relationships between the 9 objectives in the threat abatement plan............4

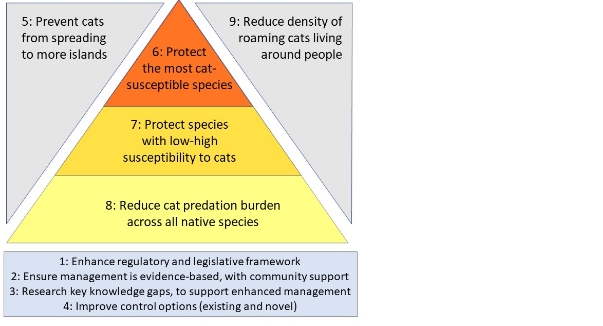

Figure 2 A diagram showing the relationships between the 9 objectives...................31

Figure 3 Objective 5: Prevent cats from spreading further.............................58

Figure 4 Objective 6: Protect the most cat-susceptible species..........................66

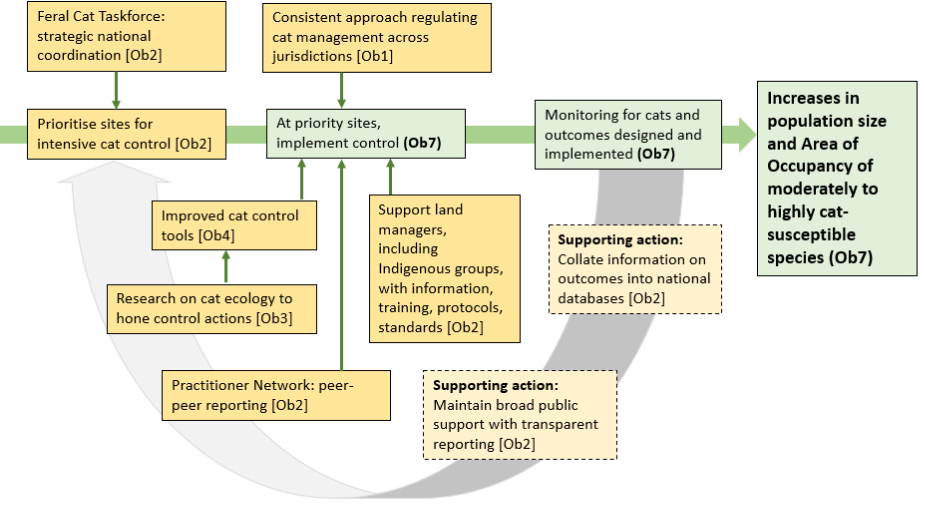

Figure 5 Objective 7: Protect moderately to highly cat-susceptible species.................71

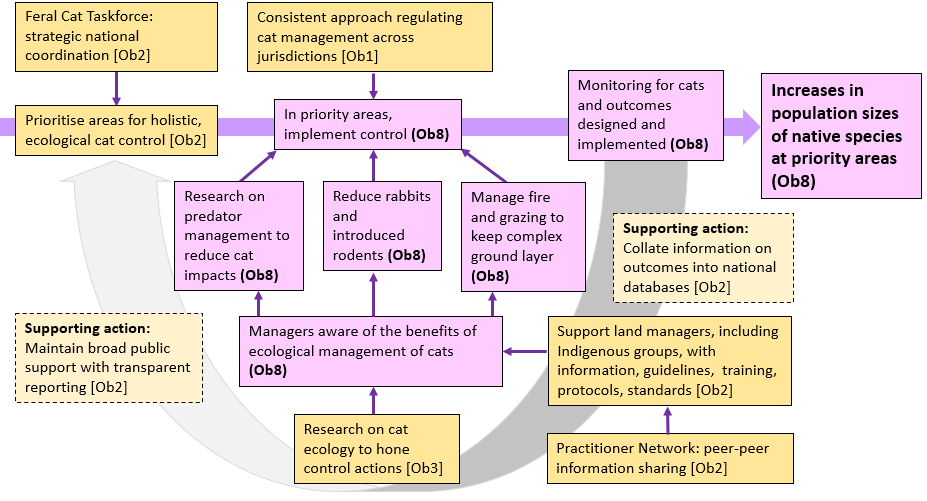

Figure 6 Objective 8: Reduce predation burden across all species.......................77

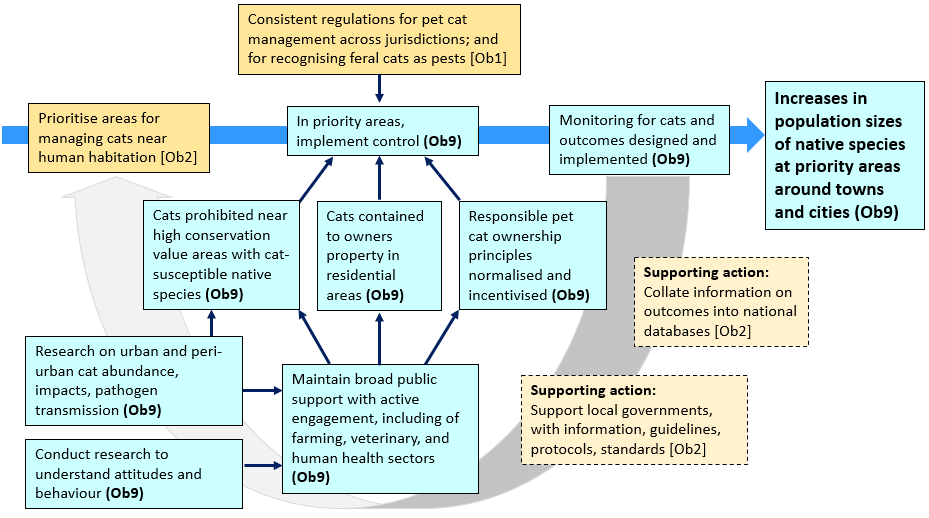

Figure 7 Objective 9: Reduce cat impacts in around human habitation and infrastructure......84

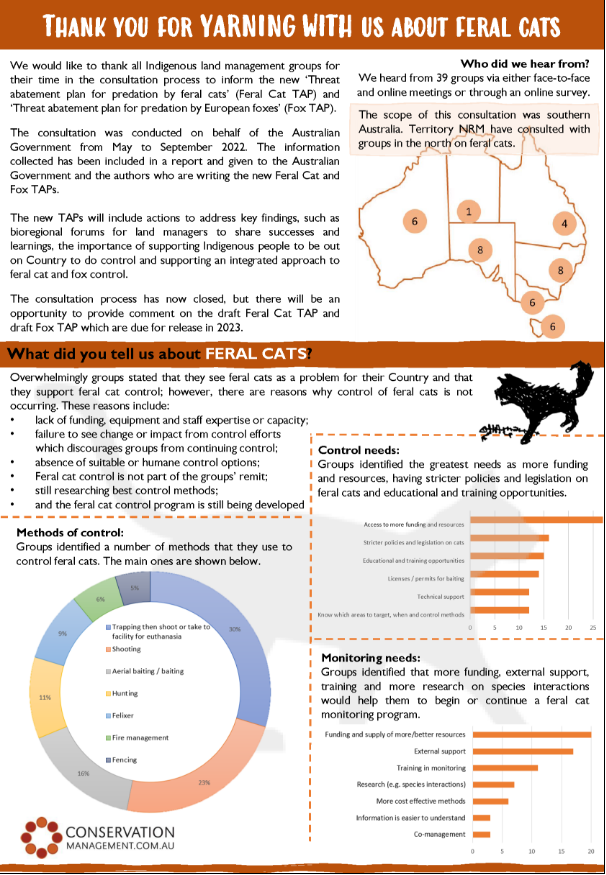

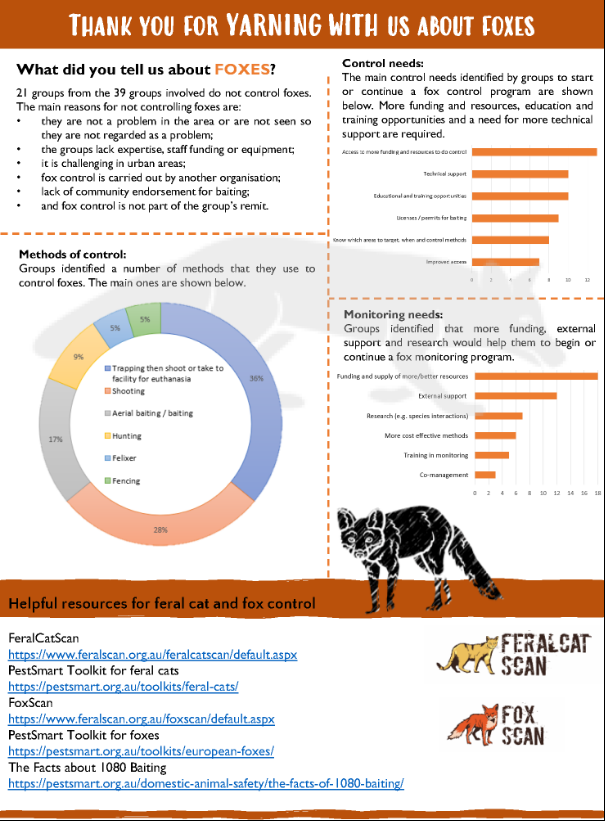

Figure 8 Summary of early engagement with First Nations groups in northern Australia......113

Figure 9 Summary of early engagement with First Nations groups in southern Australia (p. 1)..114

Figure 10 Summary of early engagement with First Nations groups in southern Australia (p. 2)..115

Tables

Table 1 Categories of susceptibility to cat predation that determine the level of cat control and management required to ensure population viability, and the numbers of extant terrestrial mammal, birds and reptile species that fall into each category 15

Table 2 Objective 1. Performance Criteria........................................35

Table 3 Objective 1. Actions..................................................36

Table 4 Objective 2. Performance Criteria........................................39

Table 5 Objective 2. Actions..................................................40

Table 6 Objective 3. Performance Criteria........................................47

Table 7 Objective 3 Actions..................................................47

Table 8 Objective 4. Performance Criteria........................................54

Table 9 Objective 4. Actions..................................................54

Table 10 Objective 5. Performance Criteria........................................59

Table 11 Objective 5. Actions..................................................60

Table 12 Objective 6. Performance Criteria........................................67

Table 13 Objective 6. Actions..................................................68

Table 14 Objective 7. Performance Criteria........................................72

Table 15 Objective 7. Actions..................................................73

Table 16 Objective 8. Performance Criteria........................................78

Table 17 Objective 8. Actions..................................................79

Table 18 Objective 9. Performance Criteria........................................85

Table 19 Objective 9. Actions..................................................86

Table 20 Approximate national costs for each objective in the plan, and overall, based on the numbers of actions that are categorised as very high ($5 million over 5 years); high ($1 million over 5 years); medium ($500,000 over 5 years); and low ($50,000 over 5 years) 92

Table 21 Research-focused actions under the strategic themes........................100

Table 22 Relevant legislation relating to cats in Australian states and territories............104

Table 23 Summary of the availability of feral cat control options in each state and territory....106

Table 24 Indicative alignment of 2015 threat abatement plan actions to 2024 threat abatement plan actions 108

Table 25 Glossary.........................................................116

Table 26 List of acronyms....................................................118

1 Summary

Predation by feral cats is listed as a key threatening process under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), in recognition of the significant detrimental impact feral cats have on many Australian threatened species. The national management of feral cats has been coordinated and implemented through a succession of threat abatement plans (established in 1999, 2008 and 2015). These plans have successively contributed to:

- major gains in knowledge about cats and their impacts in Australia

- important advances in the efficacy and range of options available to manage them

- significant conservation outcomes, especially for species most susceptible to cat predation

- broad stakeholder recognition of the threat posed by feral cats and the need for actions to reduce that threat.

This plan builds on the foundations established by, and progress made in implementing, these previous plans, and seeks to further advance the effectiveness and coordination of feral cat management across Australia, thereby reducing their impacts on Australian threatened species and other components of biodiversity.

In Australia, landholders and state and territory governments hold primary responsibility for on-ground management of established invasive species like feral cats, and the latter also make and administer legislation on companion animal management. Local governments can, to the extent relevant state / territory law permits, enact local bylaws to augment that legislation.

The Australian Government supports coordinated national efforts to control invasive species, including through the development of threat abatement plans, like this one, for listed key threatening processes.

These threat abatement plans provide the framework for coordinated and efficient national effort by identifying ambitious new actions and encouraging continued action. In doing so, they take a multi-pronged approach, presenting a comprehensive suite of the actions that, if implemented by the relevant identified parties, are expected to significantly improve threat abatement in the interests of threatened species recovery in Australia.

Furthermore, threat abatement plans present a way for all parties with a role in managing the key threatening process, in this case feral cats, to achieve more significant outcomes by avoiding duplication of effort, facilitating knowledge and resource sharing, building consistency in management approaches, addressing cross-border issues, and collaboratively addressing stakeholder interests and concerns. They are also used by the Australian Government, and others, to guide related investments. Implementing actions and contributing to achievement of this plan’s objectives, requires the combined efforts of governments, together with the actions of landholders, communities, cat owners, First Nations peoples, the private sector and non-government organisations (NGO) who deliver biodiversity protection and conservation.

The Commonwealth must implement a threat abatement plan to the extent to which it applies in Commonwealth areas, and Commonwealth legislation allows threat abatement plans to be made jointly with interested states and territories.

This threat abatement plan has been developed, and should be implemented, in accordance with the following principles:

- Stakeholder groups with interests in cat management and welfare should be respectfully engaged.

- The management of feral cats should incorporate and support the management objectives and expertise of First Nations people, and be appropriate to local contexts including local cultural values and perspectives.

- Programs to reduce cat impacts should use actions that are justified by optimising biodiversity outcomes, overall humaneness, and the sustainability of the action(s).

- Cat management should occur within an evidence-based and adaptive management framework, where monitoring leads to continual improvements in knowledge and refinement of management actions.

- Feral cat management should consider a broad ecological context – where applicable, including potential consequences on other feral animals, and conducted in a manner that integrates pest control for biodiversity outcomes.

- The priority accorded to the management of feral cats should be commensurate with the ongoing severe impacts of cat predation on much of Australia’s fauna, including many threatened species, and with the magnitude of beneficial impacts likely to arise from feral cat control.

This threat abatement plan sets a long-term goal, with a 30-year horizon:

To reduce the impacts of cats sufficiently to ensure the long-term viability of all affected native species.

Note: In this plan, ‘cat’ is used to refer to pet and feral cats collectively, whilst the terms ‘pet cat’ and ‘feral cat’ are used to refer to those specific subsets of cats. Feral cats may be further described as those living in natural environments, and those living in or around human infrastructure or heavily modified environments. Refer to section 3.1 for further explanation.

This plan seeks to reduce the impacts of cats on biodiversity; many other factors also affect biodiversity such that alleviating the impact of cats will not necessarily lead to recovery and long-term viability of cat-affected species. This threat abatement plan represents one component of a broader conservation challenge and management response. Furthermore, and as described in section 4.1.3, some other threats compound the impact of cats, and conservation responses need to recognise such interactions and manage across compounding threats. That said, cats pose the major threat to many native species, and hence the highest priority for management response.

Cat impacts on fauna arise mainly from predation, and potentially also from pathogens and diseases that are spread by cats. Impacts may be direct (e.g. cats substantially reduce a population via predation or disease), or indirect (e.g. cats disrupt ecosystems by reducing the abundance of ecologically significant species).

The goal will be achieved when:

- There are no further extinctions of native species, nor extirpations of island populations (including seabird colonies), due to impacts from cats.

- Cat-driven declines in extremely and highly cat-susceptible native species (as defined in Table 1, section 4.1.1) are stopped and reversed to the extent that these species are no longer eligible for listing as threatened as a result of cat impacts. Recognising that some cat-susceptible species may also be affected by other factors, the effective control of cat impacts may not always be sufficient to allow for such recovery, and the conservation of such species may be contingent on management of cats and other threats.

- Cat impacts are reduced across large landscapes and priority locations, such that no currently unlisted species become threatened because of impacts from cats.

To move strategically towards this long-term goal, the plan has 9 objectives to organise actions over the next 5 and 10 years (Figure 1). The objectives have been developed following review of the previous threat abatement plans, and consultation with experts and stakeholder groups, including First Nations people.

Four are cross-cutting objectives that support the delivery of the on-ground actions covered in the other 5 objectives. They include: enhancing legislative and regulatory settings; ensuring cat management is evidence-based and supported by the public; delivering research to inform management; and, improving control options.

Five objectives are designed to deliver on-ground benefits to native species affected by cats: one seeks to prevent further spread of cats to islands; 3 objectives seek to protect native species that vary in their susceptibility to cat predation; and, one objective focuses on protecting native species living in peri-urban areas.

Figure 1 The relationships between the 9 objectives in the threat abatement plan

Objectives 1 to 4 are cross-cutting, and support the on-ground Objectives 5 to 9. Objectives 6 to 8 are hierarchical, with Objective 6 requiring the strongest cat control and management for the most cat-susceptible native species.

Objectives 1 to 4 are cross-cutting, and support the on-ground Objectives 5 to 9. Objectives 6 to 8 are hierarchical, with Objective 6 requiring the strongest cat control and management for the most cat-susceptible native species.

This plan primarily addresses the threat of predation by feral cats, given this is the focus of the key threatening process for which this plan is made, but it also acknowledges and considers the role of feral cats as competitors, and as vectors for pathogens causing serious disease in native animal species, livestock and people. Further, it recognises that pet cats also cause predation and disease impacts on native species (including threatened species), and can become a source for the feral cat population, especially around human habitation and infrastructure.

This plan therefore approaches the issue of feral and pet cat management in an integrated way, noting that implementation of specific actions for both feral and pet cat management will vary with the local social, planning, and geographic context.

This plan should be read in conjunction with the background document (Background document for the threat abatement plan for predation by feral cats 2024; DCCEEW 2024a). The background document provides relevant key information, evidence and referenced sources (current to the time of its publication) to support the commentary and actions in this plan, including on feral cat ecology, distribution and abundance; impacts on environmental, social and cultural values; current and emerging management practices; and research priorities.

2 Introduction

2.1 Threat abatement plans

The Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) provides for the identification and listing of key threatening processes to biodiversity. Predation by feral cats (Felis catus) was listed under the legislation preceding the EPBC Act, the Endangered Species Protection Act 1992, and under the EPBC Act subsequently, in recognition of the significant detrimental impact feral cats have on many Australian threatened species. The national management of feral cats has been coordinated and implemented through successive threat abatement plans established in 1999, 2008 and 2015. These plans have coordinated and supported the management of feral cats nationally, and contributed to major gains in knowledge, significant conservation outcomes, and broad stakeholder recognition of the threat posed by feral cats and of the need for actions to reduce that threat. This plan seeks to build on and extend those gains.

The Australian Government develops threat abatement plans with input from other levels of government, natural resource managers, scientific experts, First Nations people and other relevant stakeholders and it then facilitates their implementation through partnerships and co-investments.

Threat abatement plans for invasive species like feral cats not only strive for better technical solutions, but also include critical enabling objectives such as:

- ensuring that knowledge of abatement methods is disseminated in accessible formats to potential users

- addressing social, legal and economic knowledge gaps and barriers

- identifying research priorities

- integrating interests relating to biodiversity conservation with biosecurity and agricultural production, and human health and amenity considerations.

Recovery plans and conservation advices for threatened species that are susceptible to predation by cats may also outline priorities for cat management and research. In some cases, management relevant to this threat abatement plan will also be relevant to other threat abatement plans (such as those for predation by the European red fox Vulpes vulpes), and vice versa, and coordination and complementarity of such plans should contribute to the effective and efficient delivery of multiple objectives.

The national coordination of pest animal management activities occurs under the Australian Pest Animal Strategy 2017-2027. The Environment and Invasives Committee, comprising representatives from all Commonwealth, state and territory governments, has responsibility for implementation of this strategy. This threat abatement plan provides guidance for the management of feral cats within that broader context.

2.2 Review of the 2015 threat abatement plan

In accordance with the requirements of the EPBC Act, the 2015 threat abatement plan for predation by feral cats (Department of the Environment 2015a) was reviewed in 2021 by the (then) Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment. The review found that the 2015 plan had provided a good national framework for actions included in the first (2015-2020) Threatened Species Strategy (Department of the Environment 2015b), and for research and management undertaken by the National Environmental Science Program, state and territory governments, researchers, local groups and other stakeholders. However, the review also found that predation by feral cats remained a major threat to Australia’s native species, and that a revised plan could build on the progress made so far. The Threat abatement plan for predation by feral cats - Review 2021 (DCCEEW 2024c) is available at: DCCEEW Website.

In addition, in 2020 the House of Representatives Standing Committee on the Environment and Energy inquired and reported on the problem of feral and domestic cats in Australia (HoR SCEE 2020), and developed a ‘plan to save Australian wildlife’, which included a recommendation for a new iteration of the feral cat threat abatement plan:

‘Recommendation 3. The Committee recommends that the Australian Government develop a clear strategy to inform its resourcing of and response to the problem of feral cats, including through a ‘reset’ of its current policy and planning. This should comprise: a. A new iteration of the Threat Abatement Plan for predation by feral cats ...’

2.3 This threat abatement plan

This plan updates the previous threat abatement plan published in 2015 (Department of the Environment 2015a). It incorporates the knowledge gained since 2015, and has been modified in light of the recommendations from the review of the 2015 plan and the report from the House of Representatives inquiry into the problem of feral and domestic cats.

This plan builds on the foundations established in the previous plans, and the progress made in their implementation. It consolidates and extends the national framework provided by the previous threat abatement plans to guide and coordinate Australia’s response to the impacts of feral cats on biodiversity. It identifies the research, management and other actions needed to ensure the long-term survival of native species and ecological communities affected by feral cats. It also aims to guide the responsible use of public resources and achieve the best conservation outcome for native species threatened by predation by feral cats, given the opportunities and limitations that exist.

Although the main impact of cats on native species is via predation (and the listed key threatening` process is focused on predation by feral cats), cats also compete with some native species for food and are vectors for pathogens that cause disease in native species, livestock and people. The plan also addresses these impacts given these factors are interlinked with, and compound, the predation impacts of cats. Cats also have broader ecological impacts, due to the disruption of ecological services provided by many cat-susceptible species.

In addition, although the plan focuses on feral cats, it includes some consideration of pet cats because they also prey upon native species (including threatened species) and can become a source for the feral cat population, especially around human habitation and infrastructure. Given the links between the pet and feral cat populations, addressing the impacts of feral cats must include improved management of pet cats.

The Threat abatement plan for predation by feral cats 2024 is supported by, and supports, the Australian Government’s Threatened Species Action Plan 2022-2032 (DCCEEW 2022). The Threatened Species Action Plan 2022-2032 outlines an action-based approach to protecting and recovering Australia’s threatened plants and animals, as well as priority places. Feral cat management is the explicit subject of two targets, and relevant to many other targets, in the Threatened Species Action Plan 2022-2032 because feral cat control is integral to improving the trajectories of many of the Action Plan’s priority species, places and habitats. Those explicit targets are:

- Target 8. Feral cats and foxes are managed across all important habitats for susceptible priority species using best practice methods.

- Target 9. Feral cats and foxes are managed in all priority places where they are a key threat to condition, using best practice methods for the location.

Targets in the Threatened Species Action Plan 2022-2032 align with the objectives and actions in this threat abatement plan.

Australian biodiversity is under pressure from many threats, including (but not limited to) habitat loss and degradation, climate change, other invasive species, and changes to fire regimes and hydrological regimes (see Murphy and van Leeuwen 2021 for further information). Reducing impacts from cats on native fauna is one of many approaches needed to prevent further declines and extinctions. Furthermore, many of these other threatening factors have direct or indirect effects on the abundance and impacts of feral cats, or contribute to the overall threat load on cat-susceptible native wildlife. This broader interactive context is considered in management actions proposed in this plan (e.g. section 4.1.3 and Objective 8).

This plan should be read in conjunction with the background document (Background document for the threat abatement plan for predation by feral cats 2024; DCCEEW 2024a). The background document provides relevant key information, evidence and referenced sources (current to the time of its publication) to support the commentary and actions in this plan, including on: feral cat ecology, distribution and abundance; impacts on environmental, social and cultural values; current and emerging management practices; and, research priorities. There are cross-references throughout this plan to the relevant supporting evidence and key references in the background document.

2.4 Consultation to inform development of this threat abatement plan

Engagement with the national Feral Cat Taskforce and First Nations organisations and rangers

Development of this plan has been informed by 2 early engagement efforts.

One involved discussions with the national Feral Cat Taskforce, which has a membership drawn from Commonwealth, state and territory government conservation and pest animal management agencies, animal welfare organisations, researchers and other stakeholders. The focus of this engagement was on the findings of the review of the previous threat abatement plan, advances in cat management options, evidence of cat impacts based on recent studies and the key themes to be addressed in this threat abatement plan.

The second early engagement focus was with First Nations ranger groups and organisations across the country. This occurred between July and September 2022 and involved virtual and face-to-face interviews, and online surveys, with people from 100 groups and organisations, and an additional 10 organisations that work very closely with First Nations partners (Conservation Management Pty Ltd 2022; Territory Natural Resource Management 2022). Many interviews occurred specifically at women’s fora, to obtain diversity of voice. This early engagement sought to understand: whether First Nations land managers considered cats a threat to Country; what cat management was already in place; what factors constrain more effective management; what could be achieved with additional support; and, the preferred form of such additional support. Summaries of this engagement are available in Appendix 7.

This engagement explicitly addresses section 271(3)(e) of the EPBC Act, that stipulates that, in making a threat abatement plan, ‘regard must be had to … the role and interests of indigenous people in the conservation of Australia’s biodiversity’. It sought to provide a longer, tailored and culturally appropriate approach to enable First Nations’ contributions to the plan and to help consider opportunities for First Nations’ involvement in the plan’s implementation.

Statutory public consultation

As required by section 275 of the EPBC Act, a 3-month statutory public consultation period was conducted between 7 September and 11 December 2023. The opportunity to provide feedback was widely advertised and the department received more than 1,600 responses through both the online consultation hub and by email, as well as a large volume of related correspondence. The common themes and technical information provided in this feedback were thoroughly considered in finalising this threat abatement plan. Some feedback provided ideas about how best to deliver on the actions and objectives identified in this plan. Where relevant, these have been noted for implementation. A summary of the common themes from the feedback, which informed the finalisation of this threat abatement plan, was prepared (Draft updated Threat abatement plan for predation by feral cats - Public consultation summary report; DCCEEW 2024b), and is available at: DCCEEW Website.

3 Cat definitions, ecology, distribution and abundance

Section 3 provides a brief overview of the ecology, distribution and abundance of cats. The background document contains further information and referenced sources, to support the material provided here.

3.1 Cat definitions

Domestic cats were derived from African wildcats Felis lybica, about 4,000 years ago, in north Africa. The domestic cat is treated taxonomically as a separate taxon, Felis catus, from its wild ancestor, and ‘domestic cat’ is the generally accepted vernacular for this species, encompassing pet cats and feral cats. Domestic cats were, and remain, highly capable of moving from pet into feral scenarios, which is partly why feral cat populations have established in almost every place where people have brought pet cats. This transition from pet to feral can occur during a cat's lifetime. For any species, the term ‘feral’ applies specifically to populations of introduced species that have established in a region or country to which they are not native from captivity or domestication, whether that establishment was deliberate or accidental.

Cats have a complex relationship with people – while they are treasured pets to some, they are widely known and seen to be a serious environmental concern. This, and the different ways in which people interact with cats, has led to many approaches to defining cats, including ones based on the level of ownership (e.g. owned, semi-owned, unowned), socialisation (e.g. socialised, semi-socialised, unsocialised), lifestyle (e.g. house cat, farm cat, stray, feral), and containment (e.g. indoor cat, free-roaming). These schemas do not always line up well, are open to interpretation, and any one cat can occupy seemingly contradictory positions – for example, a free-roaming cat could be either a pet or a feral cat, and an unsocialised cat could be an owned farm cat.

There is currently no nationally consistent classification of cats, and the legal frameworks and associated definitions are different across the jurisdictions. While consistency would be beneficial, achieving consensus across jurisdictions, cat management organisations and stakeholder cohorts may not be feasible.

For the purposes of this threat abatement plan, a categorisation of ‘feral’ cats and ‘pet’ cats has been used. This corresponds with the differences in the management focus required to address the impacts of cats on native wildlife, and the actions most likely to be in-scope having regard to the management context and location. This is not a prescribed categorisation, rather an organising framework for the information in this plan; it does not override the legal categorisations that apply in jurisdictions across Australia.

The actions outlined in this plan will need to be implemented in accordance with the legislative, planning and policy frameworks that exist in the jurisdiction within which the management is being undertaken. The actions identified under Objective 1 of this plan seek legislative, regulatory and planning harmonisation across jurisdictions, where this is possible and it makes sense to do so. These kinds of improvements would better enable landscape-scale management approaches, which may involve multiple jurisdictions, and would better support conservation organisations who work across multiple jurisdictions to protect native wildlife from the impacts of cats.

Feral cats, as discussed in this plan, are those that are not formally owned by people. Typically, they survive by hunting or scavenging for themselves and live in diverse habitats. Most feral cats live in natural environments and have no or few interactions with people. A subset of feral cats is found in and around cities, towns and rural properties; these cats may rely on resources that are indirectly (e.g. rubbish tips or abundant rodent populations), or deliberately and periodically, provided by people (e.g. placing food out for cats). These cats are sometimes called ‘stray cats’.

- In this plan, management approaches, actions and objectives for feral cats seek to reduce their impacts on wildlife, particularly the most susceptible native species. This can be done through reducing cat abundance or changing their hunting behaviours.

- Some actions for feral cats living in and around human infrastructure (refer to Objective 9), and which sometimes have a higher degree of interaction with humans, differ from those in scope in more natural environments. In these scenarios, management actions are tailored to the context whereby these cats either become responsibly owned pet cats through socialisation and adoption where possible, or they are humanely controlled where ownership is not feasible or is unrealistic.

Pet cats, as discussed in this plan, are owned by a person or people and their needs (food, shelter, veterinary care) may be wholly supplied by their owners. Some pet cats are contained indoors, but others roam.

In this plan, ‘cat’ is used to refer to pet and feral cats collectively, whilst the terms ‘pet cat’ and ‘feral cat’ are used to refer to those specific subsets of cats. For further information and referenced sources, refer to section 2 of the background document.

3.2 Cat ecology

Feral cats are medium-sized (females average 3.3 kg, males average 4.2 kg) carnivores that hunt a broad range of animal prey. They are live prey specialists, usually avoiding carrion. Across Australia, the diet of feral cats is highly variable, and also shows some seasonal variation reflecting spatio-temporal changes in the abundance of prey animal species. Mammals tend to be the dominant prey item when available, but birds, reptiles and invertebrates may also be important components of the diet. Although cat diet is broad, individual cats may ‘specialise’ on particular prey species, or types of prey. Cats are usually nocturnal and crepuscular, but will also hunt during the day (e.g. when nights are cold).

The social, mating and spacing systems of feral cats are flexible, and depend mainly on resource availability. Female feral cats usually occupy mostly non-overlapping ranges of around 5-10 km2 in size (but potentially much larger if resources are scant), with male ranges overlaying those of more than one female. Feral cats will leave their home ranges to take advantage of temporary or seasonal food bounties elsewhere. If resources are extremely limiting, feral cats can leave their ranges and roam large distances in search of food. At the other extreme, when resources are clumped and superabundant (for example, near rubbish dumps in towns), female feral cats can aggregate into matrilineal colonies (or clowders), with males more loosely attached and potentially moving between more than one colony. The mating system varies with the spacing system – cats are polygamous, but as feral cat density decreases it becomes more possible for a single male to control short-term mating access to a receptive female.

Feral cats live for an average of 3–7 years. Males begin breeding at 1 to 2 years of age. Females usually reach sexual maturity in their first year. They are seasonally polyoestrous, coming into breeding condition with increasing daylength (i.e. during ‘spring’), and then having oestrus cycles continuously until they achieve pregnancy. During oestrus, female cats are induced ovulators, releasing eggs in response to mating. The length of the breeding season is short in areas with harsh winters but can extend to 9-10 months in areas with milder conditions. Pregnancy lasts 2 months, and kittens reach independence after about 6 months of age. Female cats usually produce 1 to 2 litters, each of 3 to 5 kittens, per year; but more litters, and larger litters, are possible.

For further information and referenced sources, refer to section 3.3 of the background document.

3.3 Cat distribution and abundance

Cats were introduced to Australia from 1788. They spread rapidly across the continent, and now occupy 99.9% of Australia’s land area, in habitats as diverse as tropical rainforests, alpine environments and the driest deserts. They are present across all tenures, including protected areas. They are absent only from fenced areas built specifically to exclude cats (and foxes), and from some islands.

The population of pet cats in Australia is relatively easily monitored and is reported regularly. Populations of feral cats are not so straightforward to estimate or monitor. However, as a result of a large body of research guided by previous threat abatement plans, Australia has one of the most robust estimates for the cat population size compared to other countries in the world. Using 91 independent estimates of feral cat densities from around the country, a model for spatial variation in density indicates that the feral cat population fluctuates from 1.4 million (95% confidence intervals 1.0 to 2.2 million) when rainfall in the arid and semi-arid zones is low to 5.6 million (95% confidence intervals 2.5 to 10.9 million) when rainfall in those zones is high, and prey populations are therefore also high. In addition, there are over 0.7 million feral cats in heavily modified habitats, and 5.3 million pet cats (2022 estimate).

For further information and referenced sources, refer to section 3.2 of the background document.

4 Cat impacts

Section 4 provides a brief overview of impacts of cats, and which native species are most adversely affected. Refer to section 4 of the background document and relevant appendices for further information and referenced sources.

4.1 Predation

Cats are one of the world’s most invasive species, having reached every continent (including Antarctica, as pets) and many islands. They have been the primary or a major cause of over a quarter of the world’s bird, reptile and mammal extinctions since the year 1600. Cats have caused profound species loss in Australia, helping to give Australia the worst mammal extinction rate of any country in modern times: over 10% of the Australian terrestrial mammal species extant 250 years ago are now extinct. Of the 33 Australian mammal species rendered extinct since European colonisation, cats have mostly or substantially contributed to two-thirds of these losses. Examples of these extinct species include the pig-footed bandicoots Chaeropus spp., lesser bilby Macrotis leucura, broad-faced potoroo Potorous platyops, bettongs Bettongia spp., hopping mice Notomys spp. and rabbit-rats Conilurus spp. Cats have also contributed to 3 of 9 extinctions of Australian bird species since 1788.

Cats continue to drive population decline in Australian native animal species. Predation by cats is a recognised threat to over 200 nationally threatened species, and 37 listed migratory species (of which 9 are also listed as threatened) (Appendix 1).

With many decades of research, there is now more information on the diet of feral (and pet) cats in Australia than for any other country. Many recent analyses have compiled and analysed such information from tens of thousands of cat dietary samples. These studies have found that feral cats in Australia kill over 1.5 billion native mammals, birds, reptiles and frogs, and 1.1 billion invertebrates each year. Pet cats kill over 320 million native vertebrate animals each year in Australia. Although their overall toll is lower than that imposed by feral cats, because pet cats live at high density, their ‘local’ impacts can be much higher than that of feral cats.

Refer to section 4.1 of the background document for further information and referenced sources.

4.1.1 Which extant native species are most susceptible to cat predation?

The predation toll (impact via predation) from cats falls unevenly across species – small- to medium-sized (i.e. up to ~4 kg) terrestrial mammals, ground-dwelling or ground-nesting birds, and colonial reptiles are all more likely to be preyed on by cats. In addition, species occurring in more open, arid environments are more likely to be preyed upon. However, the likelihood of being eaten by a cat does not necessarily translate to the impact on the population, because prey species vary in their capacity to bear the predation burden from cats. For example, species with faster reproductive rates may be able to compensate for the predation toll from cats more readily than species with lower reproductive outputs.

The susceptibility of native species to cat predation is highly variable. Many extinct mammals could not, and some extant threatened mammals cannot, co-exist with even low densities of cats; and extant species that are extremely cat-susceptible are now found only in small areas (islands and mainland fenced exclosures) where cats are absent. At the other extreme, the population viability of some native species is not, or is minimally, affected by the presence of cats. Identifying where native species fall along this continuum is critical for shaping the cat management actions necessary to prevent declines and extinctions. For example, species that are most cat-susceptible can survive only if cats are absent, whereas less cat-susceptible species may thrive with less intensive cat control, or even if habitat quality is improved enough so that cat impacts are reduced or compensated for.

This threat abatement plan uses the categories of predator susceptibility defined by Radford et al. (2018) (Table 1) as a basis for identifying and organising the levels of cat control and management needed to ensure the persistence and viability of native species threatened by cats. In this plan, the cat-susceptibility of all native non-marine mammals and reptiles, land-birds and seabirds has been categorised according to this schema, using information available in species recovery plans and conservation advices, action plans, expert assessment of threats to vertebrates, and a series of papers that quantified dietary information and the likelihood of being killed or consumed by a cat. The list of mammal, reptile, land bird and seabird species considered moderately, highly or extremely susceptible to cat predation is given in Appendix 2; and details on the methods for categorising, and the current extent of protection against cats for the most cat-susceptible species, are provided in the background document. Note that there may be species (such as some invertebrates) for which the available evidence is insufficient to assess population-level susceptibility to cat predation.

Overall, 9 species of mammals, 1 species of land-bird and 9 species of seabird are extremely susceptible to cat predation; and 338 mammal, 3 land-bird, 3 seabird, and 4 reptile species are highly susceptible to cat predation. Removing cat impacts is crucial for preventing declines and extinctions in these species.

Many of the 21 mammal species identified as priorities in the Threatened Species Action Plan 2022-2032 are recognised as being extremely or highly susceptible to predation by cats (and/or in some cases, by foxes). These include the chuditch (western quoll) Dasyurus geoffroii, eastern quoll D. viverrinus, northern quoll D. hallucatus, numbat Myrmecobius fasciatus, greater bilby Macrotis lagotis, mountain pygmy-possum Burramys parvus, western ring-tailed possum Pseudocheirus occidentalis, Gilbert’s potoroo Potorous gilberti, quokka Setonix brachyurus, New Holland mouse Pseudomys novaehollandiae, northern hopping-mouse Notomys aquilo, and central rock-rat Zyzomys pedunculatus. In addition, 2 of the 22 priority bird species are highly susceptible to cat predation; these are the night parrot Pezoporus occidentalis, and western ground parrot Pezoporus flaviventris; and so is one reptile, the great desert skink Liopholis kintorei.

Table 1 Categories of susceptibility to cat predation that determine the level of cat control and management required to ensure population viability, and the numbers of extant terrestrial mammal, birds and reptile species that fall into each category.

Category of susceptibility | Susceptibility of native animal species to cat predation | Mammals (Number of species) | Land birds (Number of species) | Reptiles (Number of species) | Seabirds (Number of species) |

Extreme | Population likely to be extirpated where cats occur, and cats were, or are, or plausibly could occur in at least 50% of the native species’ range. | 9 (12 counting subspecies) | 1 | 0 | 9 |

High | Population likely to be extirpated where cats occur, and cats were, or are, or plausibly could occur in 20-50% of the native species’ range. OR Population likely to persist with cats, but with severe reduction (more than 50%) in its population size and viability, and cats were, or are, or plausibly could occur in at least 50% of the native species’ range. | 38 (48 counting subspecies) | 3 | 4 | 3 |

Moderate | Population likely to persist with cats, but with moderate reduction (less than 50%) in its population size and viability. | 24 (27 counting subspecies) | 11 (12 counting subspecies) | 10 | 18 (19 counting subspecies) |

Low / Not (levels combined) | Low: Likely to persist with cats but with some reduction in population size or viability (i.e. 0-9%); will have higher viability where cats are more effectively controlled. Not: Viability is unaffected by introduced predators. | 231 (235 counting subspecies) | 606 (624 counting subspecies | 988 | 81 |

Where subspecies exist, they are tallied with the new total shown in brackets. Vagrants and introduced species have been excluded from the tallies. Number of species tallies have been combined for ‘low’ and ‘not’ susceptibility categories.

4.1.2 Which ecological communities are most susceptible to cat impacts?

Population declines and local extirpations of native animal species due to cat predation may compromise the healthy functioning of ecological communities, and potentially even their structure and composition. For example, many of the native mammal species that are now extinct or missing from most of their previous (and in many cases, extensive) range were prodigious diggers, with their turnover of soil and litter having substantial beneficial effects on decomposition rates, nutrient and water cycling, seed spread and germination, plant recruitment patterns and fire regimes. The ecological consequences of loss or reduction in the services provided by cat-susceptible mammal species have probably had, and continue to have, detrimental impacts on some threatened ecological communities; however, this is not yet explicitly documented for any of those communities.

Given the types of species that are most susceptible to cat predation, and the ecology and behaviour of cats, the ecological communities most adversely affected by cats are probably those that: are structurally simple; occur in arid and semi-arid areas or on islands; contain keystone animal species that are ground-dwelling and within the preferred prey size range for cats (i.e. less than 4 kg); have vegetation structure which is heavily transformed by fire; and are heavily affected by fragmentation.

4.1.3 Factors that amplify cat predation impacts

The threat and impact of cat predation is moderated or compounded by other factors, including co-occurring threats. Some examples are briefly listed here.

Abundant populations of rabbits Oryctolagus cuniculus and introduced or native rodents (especially house mouse Mus musculus) support higher densities of feral cats, which can result in higher predation pressure by cats on native species. The risks to native animals from these ‘inflated’ cat populations can be acute when sudden reductions in primary productivity (e.g. a return to dry conditions after prolonged rainfall) cause rabbit or rodent populations to crash, forcing cats to switch to alternative prey species.

Changes to the fire regime or to grazing pressure that simplify the structural complexity of the ground layer may worsen the predation risk to ground-dwelling animals. This is partly because cats are drawn to hunt in, or along the edges of, recently burnt areas (especially if those areas contained high native prey density before the fire), and because the success of hunting attempts by cats increases in open areas.

Habitat clearing and fragmentation may increase predation risk, because cat density can be higher in the modified habitats surrounding the fragmented remnant vegetation, and cats may target the fragments, or their edges, for hunting. Because of these interactions, the level of cat control and management needed to protect native species will vary, depending on the context.

Cat density, activity / behaviour or impacts may be affected by the presence and density of larger mammalian predators, dingoes and foxes. The relationships are complex, probably variable, and contested (refer also to section 8.8 of this document). However, most researchers and managers agree that control of introduced predators, and their introduced prey, should be integrated.

Refer to sections 4.1.4 and 6.7 of the background document for further information on the examples listed in this section, additional examples of interactions between cats and other threats, and referenced sources.

4.2 Competition

Cats may deplete prey resources for native predators such as quolls, raptors and varanids (goannas). Cats may also use resources for shelter such as caves, hollow logs and burrows, or even large bird nests, that would otherwise be used by native species. Cats may create a ‘landscape of fear’, causing native species to change their behaviour in ways that compromise their survival, for example by avoiding foraging in the areas with the highest or best food resources.

Refer to section 4.3 of the background document for further information and referenced sources.

4.3 Disease

Cats carry many arthropods, and viral, parasitic, bacterial and fungal pathogens that can infect and cause disease in other species. Some of these pathogens rely exclusively on cats to complete their life cycle. These pathogens were introduced to Australia with the cat. The diseases they cause would not occur here if cats were absent, and these diseases will disappear eventually from areas where cats are eradicated.

Of these cat-dependent pathogens, Toxoplasma gondii is of most concern. It is a single-celled parasite that cycles between cats and any other warm-blooded animal and causes the disease toxoplasmosis. Toxoplasma gondii infections can cause morbidity and death in individuals of many native species. Toxoplasma gondii infections also affect the behaviour of individual animals in ways that make them more vulnerable to predators (e.g. poor coordination, slower reflexes, riskier behaviour). The incidence of Toxoplasma gondii infections in populations of native animal species can be high (e.g. eastern quoll, water rat (rakali) Hydromys chrysogaster), especially in colder and wetter climates, but whether these effects are sufficient to cause population-level decline is still unresolved.

Many cat-borne pathogens affect livestock and people, including 5 that depend on cats to complete their lifecycle. People are affected by cat roundworm Toxocara cati; by Bartonella henselae, a bacterium that causes cat scratch disease; and, most seriously, by Toxoplasma gondii.

People infected with Toxoplasma gondii can experience no symptoms, mild to severe flu-like symptoms, eye disease, and inflammation of the brain and heart. Women who first become infected during pregnancy may experience miscarriage or have a child with congenital deformities. More pervasively, long-term infections of Toxoplasma gondii in people are being increasingly linked to a suite of behavioural changes that predispose them to accidents, and higher risk of mental health issues including depression and schizophrenia.

Livestock are affected by all 3 pathogens that affect people, and also by 2 species of single-celled parasite in the genus Sarcocystis. Toxoplasma gondii again has the most serious impacts, as it can cause abortions of lambs. Sarcocystis infection can cause affected meat, and even whole carcasses, to be discarded from marketing which leads to lost income from livestock production.

In a recent analysis, the economic costs of the human health and livestock impacts from cat-dependent pathogens in Australia were estimated to exceed $6 billion per year. Thus, reducing feral cat density in order to reduce the incidence of disease caused by cat-dependent pathogens could achieve a One Health outcome of economic and well-being benefits to people, livestock, and wildlife.

Refer to section 4.4 of the background document for further information and referenced sources.

Note: One Health is an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimise the health of people, animals and ecosystems. By linking humans, animals and the environment, One Health can help to address the full spectrum of disease control – from prevention to detection, preparedness, response and management. See One Health for further information. |

4.4 Public amenity

In urban and peri-urban areas, feral cats and free-roaming pet cats can cause nuisance to residents and impose a substantial burden on local governments that are usually responsible for implementing the companion animal legislation of their jurisdiction. Depending on jurisdictional requirements, local governments may also control (or assist others to control) feral cats living in towns and cities. Furthermore, local governments of remote and very remote areas face some unique challenges compared to those in metropolitan areas.

A 2021 survey of local governments reported that staff considered both pet and feral cat management to be very important for public amenity and wildlife protection. Local government staff also noted that the ‘leakage’ of pets into the feral population was a serious problem and considered that pet cat management was an important component of managing feral cats.

However, local government respondents stated that cat management was very challenging, because they lacked the resources to manage feral cats adequately, and because managing pet cats was constrained by uneven levels of awareness of cat impacts among the community, uneven levels of support for responsible pet cat ownership practices among the community, and inconsistent and weak legislation and regulation across government jurisdictions that affected the ability of local government to enforce compliance. The survey report found that local governments on mainland Australia and Tasmania spend over $76 million annually on pet and feral cat management.

Refer to section 4.5 of the background document for further information and referenced sources.

4.5 First Nations cultural values

Feral cats have had, and continue to have, a range of detrimental impacts on First Nations cultural values. Many of the native animal species that have become extinct or severely depleted because of feral cat predation have cultural significance. Many were / are important totemic or food items and distinctive components of Country, and the loss of these species represents a challenge to the ongoing responsibility for the stewardship of Country. The culturally appropriate return to Country of animal species that have become regionally extinct due to feral cat predation, such as through reintroductions to large exclosures, can help restore cultural values and the perceived health and integrity of Country.

In some parts of Australia, there is now a long-standing practice of hunting of feral cats by First Nations people for food and bush medicine. Cats are also kept in many First Nations communities and outstations, for companionship and because they are believed to reduce the numbers of snakes and other problem animals. These pet cats may have significant impacts on local populations of native species and can serve as a recruitment source for the local feral cat population.

The early engagement with First Nations land managers carried out to inform this plan (see section 2.4) showed that most rangers and other land management groups consider that feral cats are a problem, because they damage Country by preying on native species (including threatened species and culturally significant species) and upset the balance of ecosystems (“cats do not belong”).

Feral cats are explicitly recognised as a threat to Country in most healthy Country plans or analogous planning documents. However, most plans do not include specific actions that focus on feral cats, most groups do not have targeted feral cat control programs in place, and views on the best methods to achieve feral cat control vary. Overall, trapping and shooting were the most common methods mentioned by groups in southern Australia, whilst managing fire was mentioned as the main control method more than trapping and shooting in the northern groups, probably in part reflecting the higher fire frequencies in northern deserts and savanna ecosystems. Many groups noted that the funding, equipment, regulatory approvals, information, or training required for lethal control of feral cats can be challenging for them to acquire. There were also some concerns about risks for non-target species (e.g. poison baits potentially being consumed by other animals, including dingoes), or that killing an animal without eating it was ‘wasteful’. Instead, many groups preferred a whole-of-ecosystem management approach for controlling feral cats. For example, managing fire was cited as a way of reducing the predation impacts from feral cats (see Objective 8, Action 8.2).

Many consulted groups noted that views about cats in the broader community were more mixed, because community members may not have access to the information about cat impacts on native species and Country that rangers do, and because some community members feel that feral cats now have a place in the system. Many groups also noted many people in their communities made a distinction between feral cats and community cats, and that the number of community cats was increasing. The key results of the early engagement were similar across the surveys carried out in northern and southern Australia (see Appendix 7).

Refer to section 4.6 of the background document for further information and referenced sources, and summaries of the First Nations engagement are available in Appendix 7.

4.6 Critical habitat, World Heritage properties and National Heritage places

The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Regulations 2000 (Part 7) stipulate that a threat abatement plan must state, among other things, areas of habitat listed in the register of critical habitat kept under section 207A of the EPBC Act that may be affected by the key threatening process concerned.

Critical habitat is registered for 5 species: wandering albatross Diomedea exulans (Macquarie Island); grey-headed albatross Thalassarche chrysostoma (Macquarie Island); shy albatross T. cauta (Albatross Island, The Mewstone, Pedra Branca); black-eared miner Manorina melanotis (Gluepot Station, Taylorville Station and (part of) Calperum Station); and Ginninderra peppercress Lepidium ginninderrense (part of Belconnen Naval Transmission Station, ACT).

Of these areas of critical habitat, feral cats were a major predator of nesting seabirds, including some threatened species, on Macquarie Island, and largely for that reason were eradicated in 2000, resulting in substantial recovery of several seabird species. There are no feral cats on Albatross Island, The Mewstone or Pedra Branca. Feral cats are not a major threat to black-eared miners, so control measures for feral cats are not a priority for the listed critical habitat for black-eared miners at Gluepot, Taylorville and Calperum. Feral cats are not a threat for Ginninderra peppercress, so control measures for feral cats are not a priority for the listed critical habitat for Ginninderra peppercress at Belconnen.

Of the 15 Australian World Heritage properties listed for present-day natural values, cats have been eradicated from the Lord Howe Island Group and Macquarie Island; have never occupied Heard Island and McDonald Islands; and have been eradicated from (or not colonised) some parts of Shark Bay (e.g. Dirk Hartog Island, Faure Island, Bernier and Dorre Islands). Cats are present and subject to some management at most other World Heritage properties (including Budj Bim Cultural Landscape, the Gondwana Rainforests of Australia, Great Barrier Reef, the Greater Blue Mountains Area, Kakadu National Park, K’gari (Fraser Island), Purnululu National Park, Tasmanian Wilderness, The Ningaloo Coast, Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park, and the Wet Tropics of Queensland). At some of these properties, cats are having some impact on the natural values for which the properties were recognised. The natural values of many National Heritage listed places are also being impacted by cats.

Refer to sections 4.7 and 4.8 of the background document for further information and referenced sources.

5 Cat management

Section 5 provides a brief overview of cat management. More information is available under the objectives in section 8, and sections 6 and 7 of the background document contains further information and referenced sources.

Cats are challenging to manage, but a research effort by many stakeholders over the past 10-20 years has increased the range of options available, and improved our knowledge of when and where each option works best. The current options are:

- Directly reducing feral cat numbers by:

- Exclusion or eradication from islands and purpose-built fenced areas on the mainland.

- Poisoning (e.g. using baits deployed from the ground or air, and Felixer™ grooming traps).

- Trapping and shooting.

- Indirectly reducing cat numbers or impacts by:

- Managing fire and grazing to maintain a complex ground vegetation layer (to reduce cats’ hunting success).

- Manipulating species interactions, for example by reducing rabbit and introduced rodent populations.

Depending on location and context, and subject to further research, harnessing any control or moderating influence that dingoes or Tasmanian devils have over mesopredators (smaller predators, including feral cats) might be a relevant indirect control option. This is further discussed in section 8.8 (Objective 8).

While actions like exclusion using fencing and retaining a complex ground layer in peri-urban bushland apply to managing pet cat impacts, generally pet cats are best-managed through responsible cat ownership practices, including containing the cat to the owner’s property, identification, registering and desexing. These pet ownership practices (refer also to section 8.9, and section 6.9 of the background document) can be more difficult to accomplish in remote, rural and regional areas, for example where access to veterinary services is limited or absent.

Each control or management option has limitations, risks or suboptimalities, such as:

- Some can only be used at very small scales relative to the overall distribution of cats (e.g. cat-exclusion fencing; Felixer™ grooming traps; intensive shooting and trapping).

- Some are only partly effective (e.g. managing habitat to reduce cat hunting success; reducing rabbit density to also reduce fox and cat density).

- Some raise welfare concerns for cats, or other potentially affected species.

- Some may have impacts on non-target species (e.g. poison-baiting).

- Some are subject to regulations that prevent or constrain implementation in all or parts of a potential control area.

- Some are subject to regulation and training pre-requisites that can be a barrier to uptake, especially to non-government land managers, including First Nations ranger groups.

- Most options are short-term or need sustained input and potentially substantial ongoing investment to achieve and maintain effectiveness.

- Most are only applicable in some geographic areas and are generally not coordinated across sites, agencies/organisations and jurisdictions.

- Many are cost-prohibitive at scale and therefore only achieve limited spatial coverage.

Singly or collectively, these constraints hinder the capability of many groups across Australia to engage in effective and long-lasting control of feral cats. For example, the early engagement process showed that low effectiveness, concerns about feral cat welfare and impacts on non-target species, regulatory and training barriers, and funding constraints, were key constraints for the control of feral cats by First Nations ranger groups.

Despite these limitations, the current feral cat control effort is preventing further extinctions, helping the recovery of some threatened species, and reducing the likelihood of some currently un-threatened species from becoming threatened. Continuing to refine and support the use of these control options is essential, whilst new control approaches are developed.

New modifications or options for feral cat control aim to increase target specificity, increase efficacy, improve humaneness, or offer longer-term solutions, when compared to existing options. For example:

- New toxin formulations and delivery systems aim to improve welfare outcomes and target specificity.

- Technologies such as network connected camera trap arrays linked to AI software and remote trap monitoring systems are vastly improving the efficiencies of monitoring and control at landscape-scales.

- Guardian dogs could potentially repel introduced predators from sites without requiring lethal feral cat control.

- Synthetic biology such as immunocontraception and using gene drives to engineer cat genomes could potentially increase the scale at which feral cat populations can be effectively managed.

Although eradicating feral cats from the continent remains infeasible in the short- to medium- term, increasing the scale and effectiveness of control, including increasing the number and extent of cat-free areas and islands, is achievable.

In food webs, cats are medium-sized predators that interact with prey species and other predators, including other introduced pest species. In particular, rabbit and rodent populations can sustain elevated populations of cats in some areas, and foxes may reduce the abundance of cats. Cat management should be integrated with concurrent management for foxes, rabbits and introduced rodents, to optimise overall conservation benefits and to reduce the likelihood of unintended outcomes.

5.1 Public support for cat management

A majority of the Australian public recognises that cats have a negative effect on wildlife, and supports the management of cats to reduce that impact (refer to section 6 of the background document). However, ongoing communication and engagement, particularly to include culturally and linguistically diverse communities, including those with recent emigrants from countries where cats are not considered a problem for wildlife, is important for further growing awareness of cat impacts and support for ongoing cat management, as well as for promoting and increasing the uptake of responsible cat ownership practices.

In addition, the early engagement for this plan highlighted the need to greatly improve access to information about feral and pet cat impacts (on wildlife, Country, and human health) and management options to First Nations communities. Currently, the mainstream platforms with information about cat impacts and control are almost universally not used by First Nations rangers, and there is little culturally appropriate information available to community members more broadly.

6 Guiding principles for plan development and implementation

The threat abatement plan has been developed, and should be implemented, in accordance with the following guiding principles:

1. Stakeholder groups with interests in cat management and welfare should be respectfully engaged.

A public that understands, and is engaged with, the issues associated with cat management will help provide the social licence required to implement this threat abatement plan. Although cats contribute to substantial environmental harm, pet cats are also much-loved family companions. It is essential that feral (and pet) cat management planning and implementation engages broadly and respectfully with all sectors that have a stake in this issue.

Compared with people in other countries, the Australian public already has a high level of awareness about the impacts of feral and pet cats on native wildlife, and generally supports management to reduce those impacts. The co-benefits of cat management for cat welfare, human health, and livestock production outcomes, in addition to biodiversity outcomes, are now well-established, and provide a basis for development and implementation of cat management that provides beneficial outcomes to all stakeholders. Focusing on the multiple benefits of improved cat management will help to maintain broad support for managing feral cats in natural environments and will encourage the public to contribute to abatement through enhanced management of pets, and feral cats around towns.

Furthermore, given the adverse impacts of cat-borne diseases on livestock production, cat management should, where possible, be coordinated across the conservation and agricultural sectors.